Turkish economy will remain under pressure after referendum

18 April 2017

Political risk will remain high, economic growth rates will be subdued by recent standards, and foreign investors are likely to be wary until greater signs of stability emerge. A commentary by Richard Grieveson.

Foto credit: Hyeong Seok Kim

In brief

- The victory for the “yes” vote in Turkey will concentrate more power in hands of its president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

- The vote does not end the period of heightened political risk. Parliamentary and presidential elections will now be held in 2019. The continued state of emergency and opposition protests against the conduct of the referendum will keep instability high.

- Relations with the EU will remain strained in the medium term.

- The domestic economy is unlikely to return to the growth rates of 2010-15. The continued state of emergency and likely tensions ahead of the 2019 election could keep consumers and businesses wary.

- From the perspective of foreign investors, the result brings some near-term respite. A “no” vote would have led to much greater uncertainty. However, in order to attract FDI and portfolio investment, and to cement the stabilisation of the lira, Mr Erdoğan will need to deliver signs of durable stability in policymaking.

According to preliminary results, 51.4% of voters approved the change to the Turkish constitution. Mr Erdoğan announced that parliamentary and presidential elections will take place in November 2019, after which Turkey will be run as a presidential system. Mr Erdoğan is highly likely to win the election for the presidency, and could then rule for two five-year terms. Emergency rule—introduced after the failed coup attempt in July 2016—will be extended for another three months.

There are four important implications of the vote:

The result was very close, indicating a polarised society, and has been disputed by the opposition and criticised by international observers.

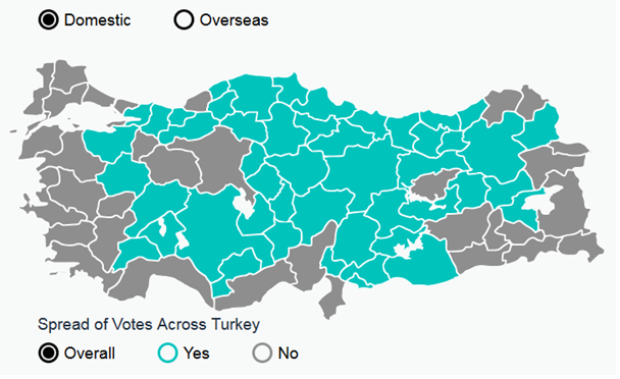

The margin of victory was small, and there was a notable divide between some of the biggest cities and rural areas. Turkey’s three main population centres—Ankara, Istanbul and Izmir—all voted “no”, as did the Western coastal areas and the majority Kurdish South-East.

According to the opposition, the “yes” campaign benefitted from municipal resources. Many media outlets in favour of “no” were either shut down, or had practiced self-censorship. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) issued a fairly damning summary of the referendum, noting an “unlevel playing field” and lack of “impartial information”. Many criticised the decision by the Supreme Election board during voting to accept ballot papers that had not been sealed.

The closeness of the final vote, and allegations of irregularities, increase the likelihood that it will not be accepted by those on the “no” side. The main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) has demanded a recount of one third of all votes, and has promised to challenge the result in the courts. While it remains highly unlikely that the vote will be overturned or re-run, this issue will remain a source of instability.

Relations with the EU will remain strained in the medium term

This is particularly problematic in the context of the refugee deal between Turkey and the EU signed in 2016. Previously, the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission had expressed reservations about the checks on the power of the presidency if the constitutional changes came into force, and stressed “the dangers of degeneration of the proposed system towards an authoritarian and personal regime”. Mr Erdoğan repeatedly attacked EU leaders during the referendum campaign, and shows no signs of letting up. Turkey’s EU accession process—which was already facing big challenges—is now even more in doubt. Mr Erdoğan has hinted at a reintroduction of the death penalty, which is a red line for the EU.

The domestic economy will probably not return to the growth rates of 2010-15

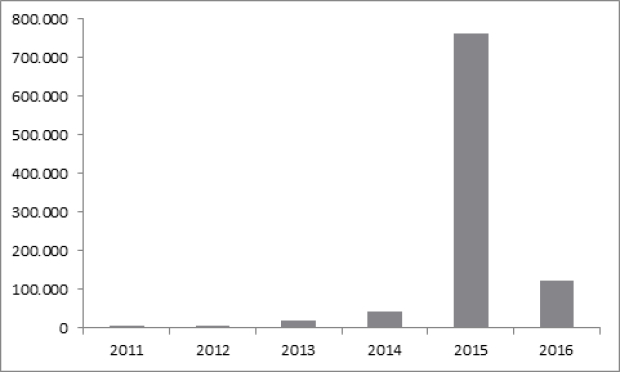

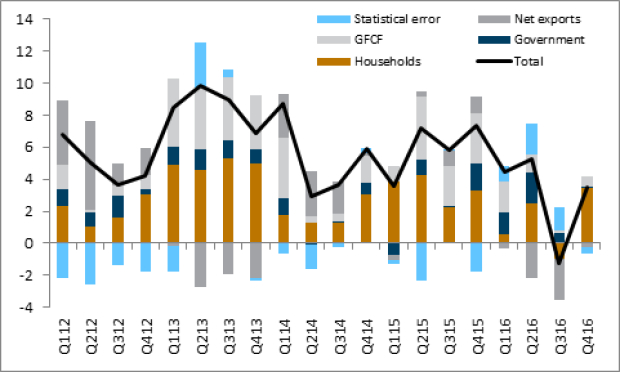

Irrespective of the referendum result, the economic challenges facing Turkey are quite significant. The ruling AKP’s economic record has been quite respectable (although not as impressive as is often claimed), and until recently Turkey had been viewed fairly favourably by foreign investors. However, since the failed coup attempt and the government’s response, the Turkish lira has weakened considerably against the US dollar and the euro, and the economy slowed significantly, contracting in the third quarter of 2016 for the first time since 2009.

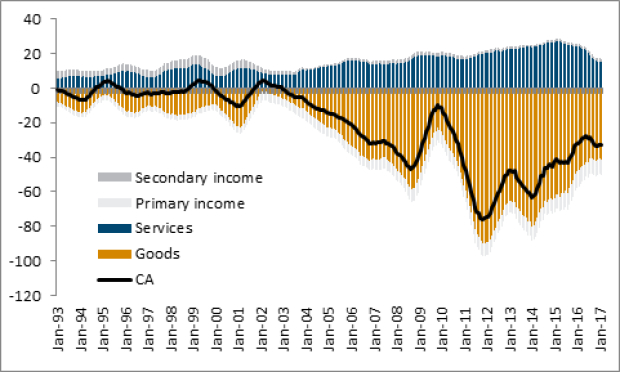

Trend growth now looks set to follow a lower path in the coming years. The financing of the current account deficit could become more difficult in the context of US monetary tightening and higher domestic political risk. The tourism sector will remain under pressure, owing both to tensions with EU members, and heightened security risk in Turkey. Meanwhile, domestic consumer and retail confidence is quite weak, and inflation has surged to a multi-year high, which will eat into real incomes.

Despite this, a more severe slowdown in economic activity appears unlikely. Confidence indicators in the construction and manufacturing sectors have bounced back in recent months, reflecting higher public spending and real exchange effective rate depreciation (REER), respectively. Historical fiscal discipline means that the government can now act counter-cyclically to support the economy at a time of weaker private spending. REER depreciation will continue to support manufacturing exports, notably in the autos sector. The banking sector remains a relative strength. Finally, the population is rising quite quickly, which will also be positive for growth.

Foreign investors will remain wary until they see signs of greater stability.

The lira initially rallied on the referendum result. Although in the very short term, a “yes” vote is probably positive for stability, it is highly uncertain whether this will remain the case in the coming months. The opposition will continue to dispute the results, and the state of emergency will remain in place for at least another three months. Portfolio and direct investors—both of which are crucial for the financing of Turkey’s large current account deficit—will want to see greater stability and predictability in policymaking. They will also want to see signs that the central bank is acting without political pressure in the face of very high inflation and a weak lira.

A more detailed analysis of the economic implications of the referendum result will appear in our upcoming Monthly Report.