War in Ukraine: A disaster with far-reaching implications

04 March 2022

The conflict will lead to a humanitarian crisis, a major negative economic shock, and a fundamental change in European integration, security, and energy politics.

image credit: istock.com/Nzpn

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created a humanitarian crisis that will unfortunately almost certainly intensify, and Ukraine’s economy is going to suffer terribly.

- International sanctions will impose strong economic and financial pain on Russia and limit its ability to contain the fallout.

- Sharp increases in energy prices will lead to ever higher inflation in the rest of Europe, and could push some economies into recession this year. Parts of CESEE, including EU member states, are likely to suffer some financial contagion.

- For Russia, absent regime change, the crisis will cut it off from most or all Western economic integration, and possibly drive it into a closer and more subservient economic and financial relationship with China.

- The EU will scramble to diversify away from energy reliance on Russia as quickly as possible, while also investing heavily in upgrading its military capabilities.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine marked the start of warfare in Europe on a scale not seen since the Balkan wars of the 1990s. Many people have already died, and as Russia launches apparently increasingly indiscriminate shelling of major cities, the death toll is likely to rise dramatically. What was unimaginable a week ago is now happening. Reports from Ukraine show an already high level of human suffering.

Projecting developments from here requires a level of military expertise that we do not possess at wiiw. Taking our cue from those who know better, we envisage two possible broad scenarios. The first is that Russia intensifies its attacks on Ukraine’s cities, causing a great deal of destruction of both human life and infrastructure, and ends up occupying a part, if not all, of the country, However, it is not likely that Russia has the resources for a long-term occupation of the country (that is not to say that it will not try for some time, at least in part of Ukraine, but it will likely have to deal with guerrilla resistance). Moscow will then be forced to the negotiating table and likely demand various written commitments from Ukraine to agree to withdraw. There are already suggestions for how Putin’s “off-ramp” could look, but to us these proposals still need some work. Hard sanctions are likely to remain in place for a long period.

A second broad possible scenario is that, in reaction to sanctions pressure and a loss of their privileges in the West, Russian elites oust President Putin and his administration and end the war. Sanctions would be gradually removed, and economic and financial ties cautiously rebuilt. We do not know enough to put probabilities on these scenarios, but we judge the first as more likely than the second.

At wiiw we are undertaking a quantitative analysis to try to understand the impact of the war on the economics of Ukraine, Russia and the rest of Europe. In advance of the publication of that paper, here we outline our mostly qualitative assessments of developments so far.

The immediate fallout; what we can (try to) measure so far

Ukraine: The impact on Ukraine’s economy and society is already dramatic and will become even more so. More than one million people have already fled, and the number of refugees may be several times that by the time the war ends. Evidence from recent conflicts suggest that the negative economic shock will be severe. As long as the war goes on, Ukraine will receive major financial (as well as military) support from much of the rest of the world. But the costs of reconstruction in Europe’s second biggest country will be enormous.

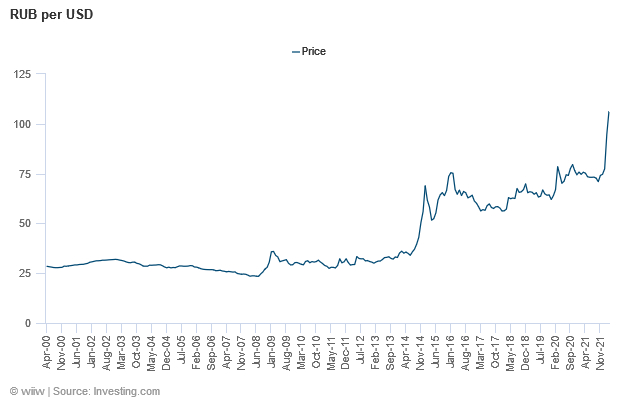

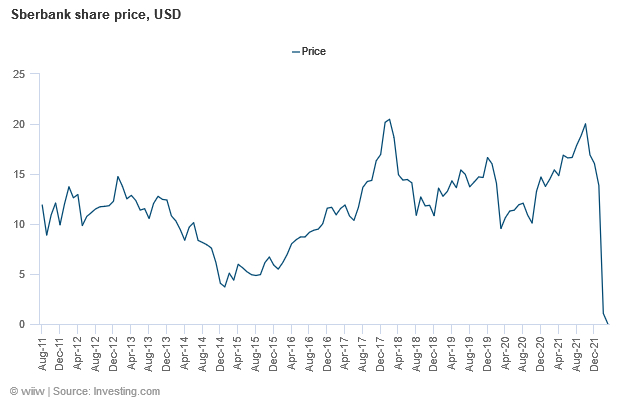

Russia: As a result of its invasion, Russia faces heavy sanctions from the outside world. Reserves held in many foreign countries have been frozen, Russia has been partly excluded from SWIFT, and it now cannot important many high-tech and consumer goods (leading to panic buying). The rouble has collapsed and inflation will sky-rocket. For ordinary Russians, there is likely to be a great deal more economic pain to follow. The Russian Central Bank has shown itself in the past to be a highly capable operator. It is facing its stiffest test yet. While it may be possible to maintain a semblance of macro-financial stability, this is likely to require extremely restrictive monetary policy (it has already more than doubled interest rates), that will further amplify the negative economic shock.

The Russian regime has spent many years building up resistance to Western economic pressure, but it clearly did not expect the speed and extent to which it would be sanctioned followed the invasion. While the authorities still have tools—not least the National Wealth Fund, some ability to tap more domestic sources of financing, and forcing firms to surrender most of their hard currency earnings—these are not infinite. Much now depends on the ability to continue to sell energy, and particularly gas to the EU. Oil traders are increasingly wary of Russian oil, forcing a large discount on barrels from the country. It is no longer unthinkable that the EU will decide to stop importing Russian gas. As EU residents are faced by scenes of humanitarian crisis on the TV news each night, public support for such a measure, and a willingness to face the costs of that, will likely grow. Studies recently produced by Algebris Investments and Bruegel try to put some numbers on this – the conclusion seems to be that the EU can cut imports of Russian gas completely, but should be prepared to pay quite a price for it.

The Russian ruble in US dollar

The share price of the biggest Russian bank Sberbank

The rest of Europe: The EU, US, UK, Switzerland and others have moved quickly and strongly to sanction Russia. Freezing the central banks’ assets abroad deprives the Russian authorities of much of their ability to cushion the overall shock. Targeting of oligarchs is also a significant step, which could lead to increased domestic pressure on President Putin. However, the truly nuclear option for the EU—stopping buying Russian gas—has not yet been taken.

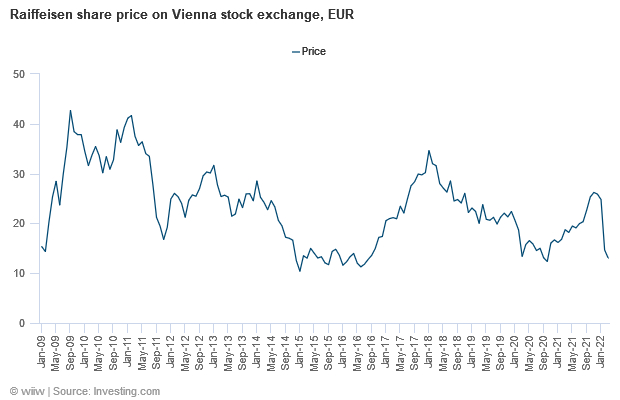

Even with the current sanctions, commodity prices have risen, adding to already strong inflationary pressures across Europe. This will weigh on real incomes, and has led to speculation that Germany will be unable to avoid at least a technical recession. Given that inflation will be commodity-driven, and that the broader economic outlook has weakened, the ECB will probably push back any plans for monetary policy normalisation this year. Several European banks with Russian exposure are under pressure. Many other European firms are cutting ties with Russia. However, overall non-energy trade and investment ties between most of Europe and Russia are small, so here the channels of contagion are limited.

The share price of Raiffeisen Bank International

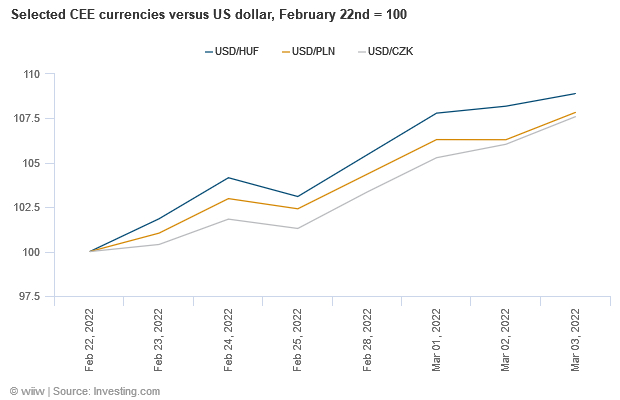

Some financial contagion is already visible in CESEE. Currencies have weakened in countries near to Russia and Ukraine due to higher risk aversion, and interest rates on government debt have in some cases increased. Investor sentiment—both domestic and foreign—in the Baltic states is likely to suffer amid fears that Russia has designs on more than Ukraine. Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and others are already seeing a massive influx of refugees. Put brutally, this is a potential windfall for their labour markets.

The Hungarian, Polish and Czech currencies versus the US dollar

Structural changes that the war could bring about

Ukraine: The outlook for the Ukrainian population and economy is bleak. The country may yet end up divided, however, with a Western part receiving major Western support to get back on its feet. It will take enormous resources, and a great deal of time, to rebuild what has been and will be destroyed in the conflict.

Russia: If Russia destroys Ukrainian cities, commits war crimes and occupies parts or all of the country, it will become and international pariah state akin to Iran or Venezuela. Its ability to generate hard currency revenues via oil and gas will be curtailed, and it will become ever more economically integrated with, and dependent on, China. Russia’s long-term growth potential, already meagre, will fall further.

The rest of Europe: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a crucial moment for both European and broader Western integration. The EU will scramble to diversify away from Russian energy sources as quickly as possible. That will include possible increased use of coal in the short run, planning new nuclear energy projects, looking for other sources of gas, and building LNG terminals. However, the central component will be a reinforcing of the green transition already underway, which in turn is the core element of the next phase of European integration (and the cornerstone of the EU’s response to economic fallout from the pandemic). As well as boosting investment in renewable energy sources, it will also be a catalyst to the development of greener transport, including major new transportation initiatives to bring many Europeans closer together.

At present, the Russian invasion looks set to presage a fundamental unwinding of 30 years of economic integration between Russia and the West. As well as the harsh financial sanctions imposed on Russia, Western firms are leaving Russia en masse. That creates the likelihood that, even if at some point sanctions are eased, February 2022 may well have marked the highpoint of European economic integration in its broadest sense.

It can also be hoped that the crisis will deliver a jolt to the EU accession process in the Western Balkans. Ukraine shows that piecemeal integration efforts from the EU can be quickly unwound. Until the countries of the Western Balkans are fully integrated into Euro-Atlantic institutions, including the EU, their development is fragile.

EU countries will also now ramp up military spending, with Germany’s announcement that it will massively increase funds for defence in the wake of the Russian invasion particularly notable. Although truly EU stand-alone military capabilities are still hard to imagine anytime soon, EU countries will play a much stronger role as part of NATO than in the past. This is likely to include a much bigger permanent presence of NATO troops in the Baltic states and Poland. Economically, financially, politically and militarily, this situation, at least for some time, will be closer to the Cold War than anything we have seen in European since 1989.