Western Balkan countries knocking on EU’s door

05 February 2018

Stronger economic integration with the EU would be beneficial for the Western Balkan countries, but they face bigger structural challenges than previous joiners.

by Robert Stehrer and Mario Holzner

photo: European Parliament, CC-BY-NC 2.0

- The accession perspectives of the Western Balkans are regaining momentum. However, a careful assessment of opportunities and challenges for the prospective members and the EU is needed.

- Despite improvements in the economic situation in these countries, many structural challenges still exist, and in general these are greater than those faced by countries that were part of previous accession rounds.

- Western Balkan economies have increased their trade links with the EU in recent years, and our analysis shows that most of the gains in terms of trade integration have already been made. Further economic integration with the bloc would only result in estimated additional trade-related economic benefits of up to 0.25% of GDP for the Western Balkan countries, whereas the impact on incumbent EU Member States would be even more modest.

- Much more significant could be a potential increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows on the back of improved EU accession prospects, and a consequent increase in export capacity and move up the value chain. This would pave the way for more meaningful and sustainable convergence with EU average per capita income levels.

The discussion on the future relationship of the Western Balkans and the EU is gaining momentum. This is a result of various factors. As part of the Bulgarian presidency, which started on 1st January this year, Western Balkan integration with the EU is one of the priorities. This could be continued by the Austrian EU presidency during the second half of this year. European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker has announced a Western Balkan accession perspective with target of accession in 2025 (although this date may only be indicative). Finally, the EU Commission announced to adopt a reinforced strategy for the region in February 2018. Although these developments suggest reason for optimism, there are also clearly many obstacles to be overcome. These were indicated in the 2016 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy pushing for reforms concerning rule of law, fundamental rights, migration issues, functioning of democratic institutions and public administration reforms, economic issues and regional cooperation. Furthermore, many bilateral political tensions as well as unresolved issues with EU Member States will not be easy to resolve, at least not in the short run.

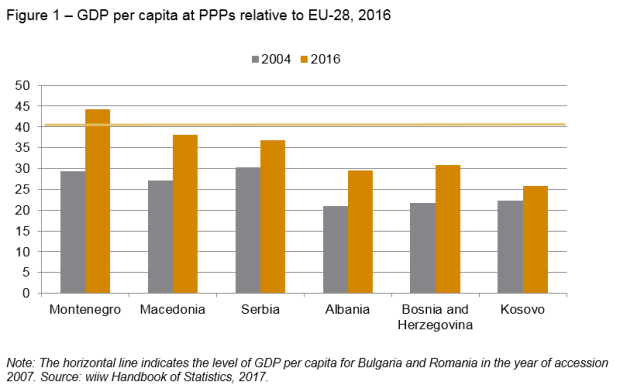

The current economic situation in the Western Balkans has improved, but is not yet comparable to that in countries which were part of previous accession rounds. In economic terms countries in the region have started to catch-up with the EU Member States in the last decade. In terms of GDP per capita at purchasing power parities the countries reach in between almost 45% (Montenegro) and 25% (Kosovo) of the EU-28 average (see Figure 1). These levels are still well below the levels reached by Bulgaria and Romania with almost 50 and 60%, respectively. However, it should be noticed that these latter two countries reached a level of GDP per capita relative to EU in 2007 – the year of their accession – of slightly above 40%. Montenegro already passed this level and Macedonia and Serbia can be expected to reach this it in the medium run. For the other three countries the gap is bigger; around 10 percentage points in the case of Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina. If these countries progress comparable to the previous decade this gap might be closed within 10 years or so. The gap is still even larger for Kosovo which also shows less significant catching-up dynamics.

The structural challenges faced by the Western Balkan countries are similar and even more pronounced than for previous accession countries. There are however a number of other structural challenges these countries face which need a further in-depth assessment. In particular, these countries are characterised by high unemployment rates (particularly youth unemployment) and low activity and employment rates. The share of manufacturing in GDP is rather low with around 5% in Albania and Montenegro, 10% in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and Kosovo and 15% in Serbia; the equivalent levels in EU-CEE countries are between 17 and 20%, or even more. Consequently, the Western Balkan countries are generally specialised in agricultural and food products, and low-tech manufacturing industries like basic metals or rubber, plastic and other non-mineral products.

Economic integration with the EU has already progressed. All Western Balkan countries have already signed a ‘Stabilisation and Association Agreement’ (SAA) with the EU which is usually coupled with granting the country easier access to the European Single Market (e.g. through reductions of import quotas and tariffs). An SAA is therefore considered to be a primary stage of a prospective EU membership as this requires the implementation parts of the current EU legislation. On top of this, the EU has already abolished its tariffs on almost all products originating from the Western Balkan countries in 2000.

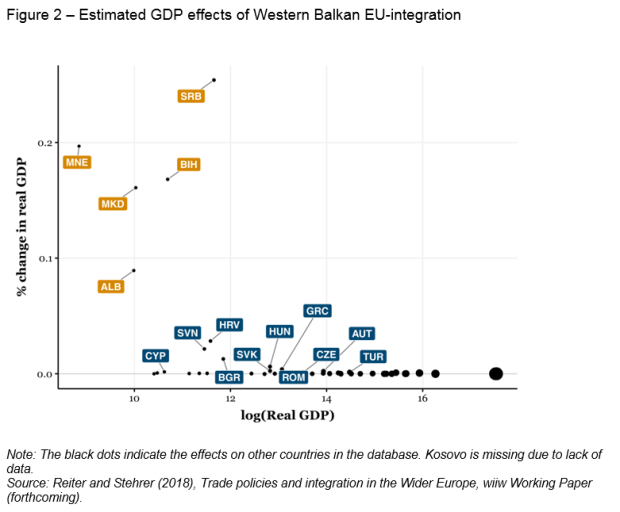

An even closer trade integration with the EU would further benefit these countries, whereas the economic benefits for existing EU member states would be modest. Drawing on a recently established and unique dataset integrating the Western Balkan countries in the WIOD database indicates that the share of foreign value added in exports are on average 30-35% for these countries. These shares are lower than those for other EU-CEE countries, mostly due to the already noted export structure of the Western Balkan countries, with high shares in agriculture and food processing. Similarly, the share of value added exports in GDP of these countries is 25-30%, which is about 10 percentage points lower than for the EU-CEE. Further, the geographical orientation of (value added) exports is more diverse for the Western Balkan countries and less oriented towards the EU. Applying a structural gravity model we show in a forthcoming paper (Reiter and Stehrer, 2018), that signing a Stabilisation and Association Agreement with the EU (which means implementing EU law) has led to stronger bilateral trade flows, even though the EU abolished its tariffs on almost all products originating from the Western Balkan countries already in 2000. This indicates a trade facilitation effect as a result of the SAA that acts on top of tariff reductions or eliminations. Moreover, we find that EU accession would result in additional trade gains of between 0.1 and 0.25% of real GDP (see Figure 2). The effects on the existing EU member states are however more modest. Among these countries, Slovenia, Croatia and Bulgaria would gain the most, adding between 0.03 and 0.05% of GDP, due to stronger trade linkages with the Western Balkan countries.

Summarising, an enlargement of the EU with the Western Balkan countries faces many political and economic challenges which are not impossible, but also not easy, to overcome. The chance that this happens by the 2025 target - as indicated by some Commission statements – is (maybe too) ambitious and depends heavily on the political will of both sides. In economic terms, most of the countries could reach the income level relative to EU comparable to Bulgaria and Romania in 2007 over the medium to longer term. However, the structural economic challenges faced by the Western Balkan countries appear more significant, though not impossible, to overcome. This process could be assisted by increased cooperation and support, e.g. in heavily needed infrastructure projects important for connectivity within and beyond the region. Greater confidence about the region’s EU accession prospects could spur higher FDI inflows, leading to greater export capacity and a move up the value chain. In turn, this would provide a boost to per capita income convergence with wealthier EU member states. However, the various political strains amongst the Western Balkan countries and in relation to other EU Member States remain a major challenge.