European burden sharing of corona crisis costs: Why Germany should lead the way

20 April 2020

The German government should seek rapprochement with the governments in Rome and Madrid to achieve viable solutions for European burden sharing of corona crisis costs.

- A highly divergent fiscal policy response by member states would result in an uneven recovery from the corona crisis and increasing economic polarisation between Northern and Southern euro area countries.

- Therefore, a strong and common European fiscal policy response will be needed to prevent the euro area from disintegrating over the course of this crisis.

- What is needed for the recovery fund is "new money" – €1000 billion (around 8% of the euro area's output) should probably be regarded as the lower limit.

- Germany is Europe’s political and economic powerhouse. In the debate surrounding the details and financing of a "recovery fund", Germany will therefore have to play a key role.

Germany should seek rapprochement with Southern euro area countries

In the 1960s and 1970s, Willy Brandt did not allow his main policy guidelines to be limited by the narrower scope of action that political competitors and internal critics wanted to grant. Rather, within the framework of the New Ostpolitik, Brandt focused on rapprochement in relations with the Eastern Bloc countries. In doing so, he actively communicated to the German population the necessity and usefulness of long-term integration efforts. The focus on common interests and peacekeeping was underlined by symbolic acts such as the "Warsaw knee fall".

Of course, Brandt's New Ostpolitik in relation to the Eastern Bloc countries at the time has to be seen against the background of Germany’s legacy from the Second World War. Germany’s position in Europe today is different, but the economic track record of the euro area has been suboptimal over the past ten years, especially in the southern euro area – and it is not without justification that countries such as Greece, Italy and Spain point out that Germany shares responsibility for some of the most devastating policy outcomes since the start of the Euro Crisis. Germany should now seek rapprochement with the governments in the southern euro area countries that are all interested in a stronger common European response. In doing so, Germany would not only act in solidarity, but would also do justice to its long-term self-interest.

After all, Germany's export-driven economic model has benefited greatly from the European Economic and Monetary Union over the past twenty years. The current situation offers the German government the opportunity to lay the foundations for short-term survival and long-term prosperity of the euro area through rapprochement and increased integration efforts. However, this requires clear political signals in the upcoming negotiations on a EU "recovery fund", which will be most essential for Italy and Spain if these countries are to successfully overcome the crisis once the lockdown measures can be lifted.

The negotiations on the "recovery fund" will enter an important round on Thursday (April 23rd) at a meeting of the heads of state and government. If Germany were to take the lead in finding a viable solution for European burden sharing of the costs of the crisis, relations with the southern euro area countries could also be improved. The current governments in Rome, Madrid and Lisbon are calling for more Europe in terms of more inclusive efforts to tackle the crisis. A focus on rapprochement by the German government can therefore be expected to fall on fertile soil.

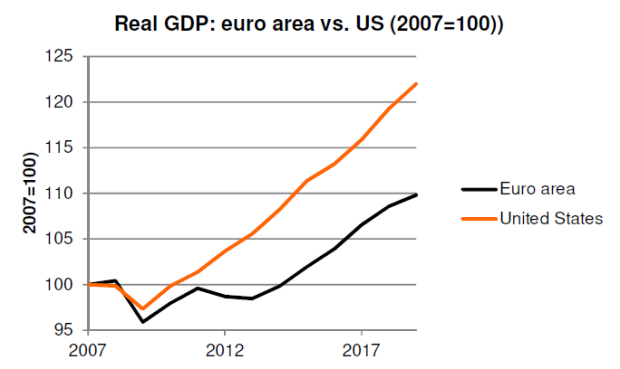

The problematic macroeconomic track record of the euro area

Since the outbreak of the financial crisis some ten years ago, economic development in the euro area as a whole has fallen far behind that of the USA, where the mix of monetary and fiscal policy has been more conducive to allowing for economic recovery. Triggered by a premature shift to fiscal consolidation measures, the euro area experienced a double-dip recession in 2011-2013, which set in shortly after the 2008/2009 recession associated with the financial crisis. The double-dip stopped the economic recovery in the southern euro area countries. In 2013, the unemployment rate shot up to more than 25% in both Greece and Spain. By contrast, Germany's economy came through the years of the euro crisis unscathed, as exports to China and other fast-growing international markets were booming. But the German export model – which entails very high current account surpluses that are regularly criticised internationally – was and is not transferable to all other euro area countries.

Data: AMECO (Autumn 2019); own calculations.

When the International Monetary Fund (IMF) presented an analysis in 2013 that clearly showed that the front-loaded fiscal consolidation policies introduced had considerable negative macroeconomic effects – and were therefore not "growth-friendly", as was regularly argued on the German side. German Chancellor Merkel and the German Finance Minister Schäuble nevertheless continued to make clear political demands: fiscal consolidation and further "structural reforms" (i.e. deregulation of the labour markets) were claimed to be the only way forward if crisis-ridden countries wanted to restore competitiveness and resume growth. Driven by a crisis narrative that was not based on facts, German and European leaders ignored that the further deterioration in the macroeconomic situation in the southern euro countries as a result of austerity and reform measures also had a negative impact on public debt sustainability.

Fixation on damaging austerity policies

In response to the financial crisis, the costs of which had led to a sharp rise in public-debt-to-GDP-ratios across the euro area, Germany pushed for tightening the EU’s fiscal rules. The "debt brake", which had already been introduced as a German constitutional law in 2009, was also to be introduced in all other EU countries. This German initiative gave rise to the European Fiscal Compact; in line with the German model, the signatory states thus committed themselves to introducing national "debt brakes" that restrict the scope for fiscal policy action, although not all signatory countries implemented the debt brake as a constitutional law as in Germany. In the context of the reform of the Stability and Growth Pact and by strengthening the budgetary monitoring of the nation states by the European Commission, Germany also urged that the fiscal policy thumbscrews in other euro area countries be tightened more firmly in the long term.

When the Greek people protested against the troika austerity programmes by voting for parties opposing further rounds of excessive fiscal consolidation, the German Finance Minister Schäuble was credited with the quote that new elections will change nothing, arguing that there are rules and agreements that cannot be changed – no matter the election outcome. In any case, Schäuble's public approach toward Greece sparked off a debate about a crisis of democratically legitimized economic policy, especially since the austerity and reform measures for the affected populations in the south of the euro area had for years shown no light at the end of the austerity tunnel.

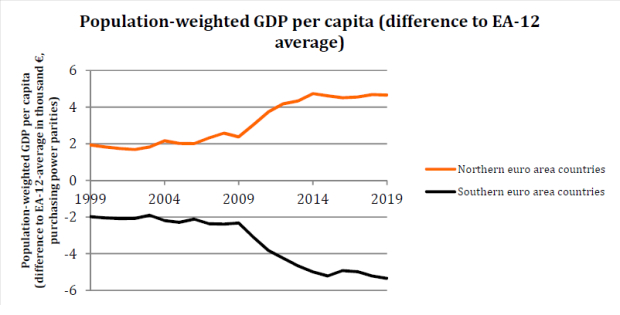

Economic divergence fuels political polarisation

The North-South polarisation within the Eurozone has intensified in light of the negative economic policy track record over the course of the Euro crisis: the gap in per capita income has widened considerably, and the underlying macroeconomic dynamics have also fuelled political polarisation between the euro area’s member states.

Data: Eurostat; own calculations. Northern EA: Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Finland, Austria; Southern EA: Greece, Spain, Italy, Portugal.

A few former decision-makers have now at least partially admitted to the mistakes of European economic policy in recent years. Perhaps the most prominent of them is the former “Chief Economist” of the European Commission, Marco Buti, who has now called the fixation on increased fiscal deficits and public debt as causes of the euro crisis a costly mistake, and who also mentions critically the counterproductive effects of the front-loaded fiscal consolidation measures that were pushed in the South of the euro area. However, to this day, the critical reflection of political leaders in Germany concerning their own involvement in European economic policy decisions remains comparatively underdeveloped. Yes, of course, many things also went wrong in the southern euro area countries; Rome, Athens, Lisbon and Madrid each have a host of homemade problems - such as dysfunctional banking systems and supervisory failures, excessive influence of individual interest groups, fickle politicians and regional disparities that started long before but have worsened during their Euro membership.

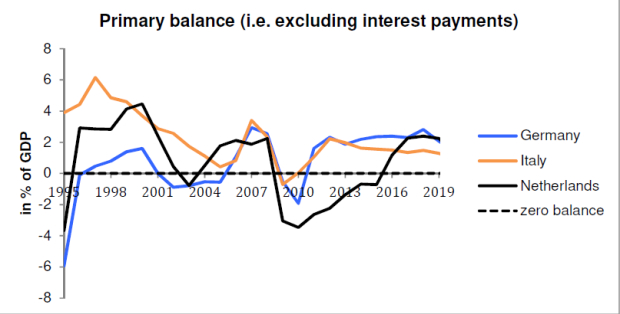

But would the southern euro area countries be in a better position today to cope with the corona crisis, and would European cohesion have been stronger in recent years if the euro crisis policy had been less restrictive? On the one hand, the Italian state, around which much of the current debate revolves, has consistently persistently posted primary surpluses over the past twenty years, which points to considerable fiscal consolidation efforts in the face of large interest payments on legacy debt, but certainly does not at all fit into the usual narrative of fiscal profligacy in the South. On the other hand, the German government has for many years refused to acknowledge its own rule breaches regarding excessive current account surpluses within the framework of the EU's "Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure". Such inconsistencies in the German discourse are still awaiting resolution.

Data: AMECO (Autumn 2019).

Scars from the euro crisis: The ESM debate

The years of consistently receiving “economic policy lessons” from Berlin have left scars in the southern euro countries that are clearly visible in the current corona crisis. This can be illustrated using the example of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The EU finance ministers recently agreed on the establishment of a new ESM credit line. As requested by Italy and other countries, this is only linked to minor conditionality, but it is limited to covering the health care costs to combat the corona pandemic. This severely limits the macroeconomic stabilisation effect of this ESM credit line, because government spending on health care costs will play a very small role in the overall view of the crisis costs. Moreover, the domestic political reaction in Italy already indicates that it could be that the ESM credit line will not be used anyway, simply because it is associated with the negative experience of humiliating restrictions on national policy space during the euro crisis: Conte and his government may not politically survive the criticism of the Italian opposition if they are to activate an ESM credit line.

Germany's own interest in a strong "recovery" fund

Unlike in the years from 2010 onwards during the euro crisis, Germany will not be able to rely on its export-driven growth model to more than compensate for the weakness of other euro area countries. This time, China and other emerging Asian economies will also suffer greater economic growth losses, which will lower their demand for imports; the global economy as a whole has been hit hard by the repercussions of coronavirus, and the partial interruption and questioning of global value chains will make an export-based recovery strategy more difficult to implement in the medium term as well. The prospects for booming global markets for German export goods have simply become gloomier. It is therefore even more in Germany's own economic interest that the member states in the euro area do not fail to recover from the Corona crisis for years to come, but instead find support through European programmes that are jointly financed.

At the last Eurogroup meeting, the EU’s finance ministers still did nothing concrete to resolve the dispute over how to finance the longer-term efforts to revive the economy throughout the euro area after the corona lockdown. However, there is agreement to set up a "recovery fund". How large this fund should be and how the burden sharing can be financed is still unclear. Germany's government still has the chance to take the lead in pushing for a strong European response in the upcoming negotiations on this recovery fund. This would not simply be an act of solidarity, but would also be in the country's own interest, because it would support a recovery of the European economy as a whole and prevent persistent crisis and stagnation in a sizeable part of the euro area, from whose existence the export-driven German growth model has benefited greatly over the last twenty years.

The debate on "Corona Bonds"

Since the start of the Corona crisis, debates have strongly focused on "corona bonds": nine euro countries (including all southern euro countries) had jointly called for the (one-off) issuance of European bonds to finance the fight against the crisis. Seven prominent German economists had also campaigned in the FAZ and in a number of other European newspapers for a solution through the joint (one-off) issuance of common bonds. But both Chancellor Merkel and Finance Minister Scholz had quickly put the initiative of the nine heads of state and government in its place.

Germany's rejection follows the pattern that is well known from the long years of the euro crisis: there are still fears that joint borrowing could create incentives for future fiscal policy excesses in individual member states ("moral hazard") and place an excessive burden on German taxpayers. This is despite the fact that, according to the relevant proposals, the Corona bonds to be raised jointly over a time-limited period in an exceptional situation and the European Central Bank could have bought up the issued bonds and kept them on its balance sheet, so that no costs would have been incurred for the taxpayers in the northern euro countries as long as no country has to default on its obligations

Even if there is the possibility for Germany to work towards the establishment of a powerful recovery fund, the details and financing of which still need to be worked out, German policy-makers should not be under any illusions about the damage already caused by the rapid rejection of the idea of Corona bonds in March.

The solution for a European burden sharing does not necessarily have to be called "corona bonds". But the symmetrical Corona shock, which affects all EU member states, would have to be followed by a symmetrical European response. But a symmetrical fiscal response is not possible if every country is left to fighting the crisis on its own. The crucial question, then, is how to finance a European response.

Not all proposals concerning the use of new European debt instruments require joint liability of individual member states. The technical discussion is certainly important, but first of all clear political signals from the German government are needed to move the Netherlands and other northern euro area countries towards a stronger European response. Germany is large and powerful enough to push for a stronger European response.

What is the German population's attitude toward common European debt instruments?

Of course, if Germany were to participate in significant European burden sharing, at least parts of the parliamentary opposition and the German population would respond with resistance. But it is not set in stone that the government parties would be harmed in their electoral outlook if they were to take up the challenge of communicating the necessity of rapprochement with Italy and the other southern European countries in a quest for a powerful "recovery fund".

According to the results of a recently published survey by the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, the attitude toward common European debt instruments among the German population is much less problematic than is often assumed: "When given an opportunity to consider all aspects of the matter, German citizens are willing to agree to forms of debt mutualization to keep the Eurozone intact.”

Politics is sometimes described as the art of the possible. But if governments never try, they will never succeed. This is very relevant when it comes to the debate on common European debt instruments. The Grand Coalition in Germany has so far made no attempt to explain the economic and political advantages of such instruments to the German people. To do so, the Chancellor would have to abandon her proven tactic of waiting until the next crisis escalates and, together with the Finance Minister, advocate a more active approach.

The debate on the "recovery fund"

If the Eurozone is to have a future, the responsible politicians in Germany must try to convince the public of the necessity and usefulness of a stronger European response. Of course, great efforts of persuasion will also have to be made in the Netherlands, Austria and Finland to convince the populations in these countries of viable common solutions that presuppose a rapprochement with the southern euro countries. But Germany is the politically and economically strongest country in Europe, and the experience gained from the euro crisis suggests that Germany – especially if it can find a common line with France – would be in a position to bring the governments of other northern euro countries on board and integrate them into political alliances.

An important meeting of the heads of state and government will take place on Thursday (April 23rd), where the roadmap and initial decisions on the "recovery fund" will be discussed. The EU Commission has already announced that the details of the "recovery fund" and its financing will be negotiated under the umbrella of the long-term EU budget. Experience with the extremely controversial EU budget negotiations from pre-Corona times points to the dangers of this strategy. For the past insistence of some EU member states – above all Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden – on hard limits for their countries' future EU contributions gives rise to fears that the "Reconstruction Fund" will be way too small. In the recent past, negotiations about a fiscal instrument for the whole euro area were also folded into the negotiations on the EU budget, and the outcome was an agreement on a tiny budget without real firepower (BICC).

Germany’s key role

It would not help either if the EU Commission were to try to generate "leverage" from existing money pots in order to artificially inflate the sums in question – as has recently been the case, for example, with financing issues related to the "Green Deal" and the Juncker Investment Plan. Furthermore, integration into the EU budget negotiations does not solve the controversial financing issues. What is needed for the recovery fund is "new money" – €1000 billion (around 8% of the euro area's output) should probably be regarded as the lower limit. The recovery fund should preferably be financed with a new common European debt instrument, because otherwise much larger (one-off) EU budget contributions by Germany and other northern member states would be needed, which seems to be even less likely if the experience of the tedious EU budget negotiations in pre-Corona times are any guide.

Germany could send out a strong European signal in the upcoming negotiations on the “recovery fund” that will resume at the meeting of the heads of state and government on Thursday (April 23rd). It is up to the German government itself not to make itself small in its negotiating tactics, but to focus on rapprochement with governments in the southern euro area. We can learn from the past that taking the lead can pay off in the long term. Willy Brandt's New Ostpolitik is an important example of how the public can be convinced of the necessity and usefulness of rapprochement and integration.