Fixing the crumbling framework of international trade

25 October 2018

The weaknesses of the WTO have been exposed by the ‘Trump tariffs’ and counter-reactions by the EU, China, and Canada. An overhaul of the system is long overdue.

By Julia Grübler and Ralph Janik[1]

- Protectionist US tariffs on the grounds of national security may not be justified, but unilateral responses by the EU, China or Canada are not in line with WTO regulations either.

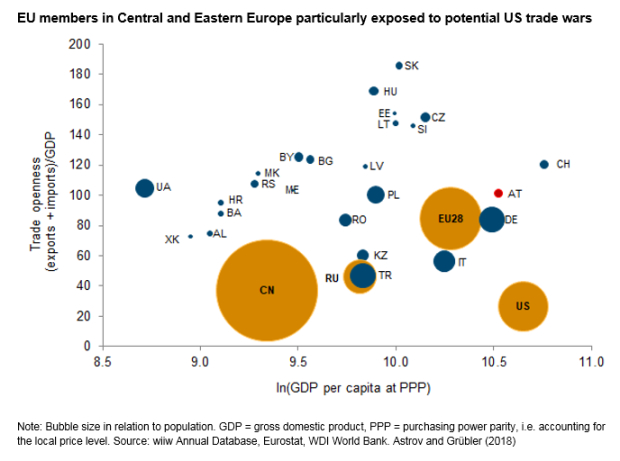

- For the EU and its many small, open economies, a functioning rules-based framework for international trade is vital.

- The EU therefore recently engaged in discussions on WTO reform in different country settings, potentially taking the important role of a mediator between the US and China, the two biggest economies in the world.

‘Trump tariffs’ pushing reform

The list of possible reforms of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is extensive and contains numerous complex issues. Some have become particularly relevant since US president Donald Trump took office in 2017. Anti-free trade and anti-China policies have been promoted by US trade representative Robert Lighthizer and President Trump’s advisor Peter Navarro, notoriously known for his book ‘Death by China’ and the corresponding Netflix Documentary.

Under the Trump administration, protectionist rhetoric started to become protectionist trade policy in March 2018, when tariffs on imports of steel (25%) and aluminium (10%) into the US were announced – with temporary regional exceptions. The US justified these tariffs on national security grounds, referring to Article XXI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), allowing the US to take “any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests.”

As of 1 June 2018, they also applied to Canada, Mexico and the EU. Considering extra tariffs on steel and aluminium imports for national security reasons unjustified, these trading partners enacted previously announced counter-tariffs on US products.

The fallout for the EU

For the EU, countermeasures against the US resulted in threats of 20% tariffs on European cars, stirring up fears of a full-scale trade war between the EU and the US. However, in July 2018, this worst-case scenario was prevented, at least temporarily. Mr Trump and European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker agreed to work jointly on eliminating tariffs and non-tariff measures and subsidies for industrial goods and reforming the WTO.

However, the story does not end here. After all, the EU is a very open economy (measured in terms of trade/GDP). This means that even if it is not significantly affected by direct US tariffs, it will suffer from trade diversion effects caused by other US trade disputes, particularly with China, with which the US is already caught in a spiral of retaliatory trade measures.

Everyone is violating WTO law

Much attention has been paid to the illegality of Trump’s tariffs. On the one hand, they exceed the US’ bound tariff rates. On the other hand, the exceptions for Argentina and Australia violate the Most Favoured Nation principle.

At the same time, the reactions by the EU, China, and Canada are also likely to violate WTO law. WTO law generally does not allow unilateral, i.e. non-authorised, reactions to violations by other WTO members. Even when it does – as in the case of permitted reactions to so-called safeguard measures, which allow countries to impose tariffs in order to protect their domestic industries from (potential) injury resulting from a surge in imports – this legal option does not exist in the case of the ‘Trump tariffs’, since the US has not imposed safeguards in the first place. As already stated, the tariff hike was related to national security concerns.

In a best-case scenario, the ‘Trump tariffs’ would have never been imposed. In the second best case, the EU, Canada, or China would have waited for a decision by the WTO (the Dispute Settlement Body) authorising countermeasures such as retaliatory tariffs before taking action unilaterally. However, in the end the EU, Canada and China chose to act unilaterally. Two major shortcomings of the WTO explain this behaviour:

-

Lengthy proceedings: One of the reasons not to wait for authorisation is that WTO proceedings take at least 15 months and up to 18 months if the respondent (i.e. the US) appeals the initial decision. In reality, they take considerably longer than the law prescribes. Moreover, proceedings are expected to take even more time in the future because of the US blockade of the appointment of new members to the Appellate Body. If it continues for too long, the already struggling Appellate Body will become completely dysfunctional.

- No compensation, no punishment: In addition to the duration of proceedings, the set of permissible reactions probably explain why China, the EU and Canada did not wait for the final outcome of WTO proceedings. First, there is no compensation, as it requires the violating WTO member’s consent. Secondly, and relatedly, WTO law foresees neither reparations for damages suffered from these violations (in contrast to virtually every domestic legal system), nor a distinctively punitive element. Rather, allowing for retaliatory measures by negatively affected trading partners is merely supposed to promote compliant behaviour, i.e. restore conformity with WTO law. If a country ends its trade policies violating WTO regulations before the WTO Dispute Settlement Body authorises countermeasures, it faces no consequences at all (the ‘temporary breach puzzle’, as Wu put it). In addition, whether a trading partner can respond effectively in a ‘dollar for dollar’ fashion also depends on its market power. While the US, China and the EU might be seen as economically on a par, other economies affected by ‘Trump tariffs’ might not have the means to stand up to the US.

Reform proposals are on the table

The Swiss novelist Max Frisch famously stated that “crisis is a productive state. One simply needs to remove the smack of catastrophe”. While we may keep lamenting the decline of international law in general and international trade law in particular, the current situation can – and should – be seen as an opportunity to address some fundamental and longstanding problems of the WTO and its legal regime.

Indeed, Canada and the EU recently published discussion papers on possible WTO reform. Suggestions range from making the WTO monitoring system more effective, to strengthening the dispute settlement system and a general ‘update’ to 21st century needs, e.g. by addressing digital trade, state-owned enterprises and industrial subsidies, or the concerns of the increasing number of economically weaker WTO member states. The EU approaches different topics of WTO reform in different (country) settings:

- With the US: On 25 September 2018 a joint statement on a trilateral meeting between trade ministers of the US, Japan and the EU was achieved. It shows that these three economies found a common ground for WTO reform and future cooperation in their common concerns related to Chinese trade and investment practices.

- With China: Diplomatic support for a functioning multilateral trading system was also reaffirmed at the 12th Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) held on 18-19 October 2018 in Brussels and attended by high-level representatives of 51 Asian and European countries.

- Without the US and China: The upcoming Ottawa Ministerial on WTO Reform (24-25 October 2018), however, will take place without the biggest two economies in the world discussing three themes:

Theme 1: Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the WTO monitoring function

Theme 2: Safeguarding and strengthening the dispute settlement system

Theme 3: Modernising the trade rules for the twenty-first century

The topics and aims discussed in these various settings seem quite similar. However, their interpretation could vary greatly. While political and economic fronts between the US and China harden, the EU continues discussions and negotiations with all parties. Thereby it is potentially assuming the important role of a mediator in the process of the reform of the global trading system.

[1] MMag. Ralph Janik works at the Media platform Addendum and teaches international law at the University of Vienna, the Webster Vienna Private University and the Danube University Krems. Contact: ralph.janik@univie.ac.at, https://ralphjanik.com.