Iran: New sanctions starting to bite

18 December 2018

The difficulties faced by Iran under new US sanctions should not be underestimated. However, the government should not respond with a hard-line approach.

by Mahdi Ghodsi

The United States reinstated the toughest ever US sanctions on Iran on November 4th, targeting energy, shipping and shipbuilding, and the financial sector. This is part of a campaign of 'maximum pressure' on Iran, which aims to isolate its economy from the international economy, and thereby to minimise Iran’s foreign revenues through exports in general and oil in particular. Since the new sanctions came into force, EU banks have not accepted any transactions from Iranian lenders, and EU energy companies have not taken imports from Iran. However, eight countries – China, Greece, India, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Turkey – are temporarily exempted from these US sanctions, and could benefit, at least for some time. South Korea and Japan had stopped importing Iranian oil some months before the latest sanctions came into force, and will only start loading Iranian oil in January with generous discounts from Iran.

Ordinary Iranians are caught between a rock and a hard place

Iranians are pressed between two forces. On the one hand, the US is imposing crippling sanctions against them, while on the other, their own government is ruling their society with strict Islamic law and at the same time is asking them to resist the economic hardship of sanctions. Although humanitarian trade such as primary food and pharmaceutical products are exempted from US sanctions, financial sanctions have damaged Iran’s ability to make any transactions in foreign currencies. The challenges faced by the Central Bank of Iran have caused long delays in importing cargos of foodstuffs and livestock feed. They are anchored in the Persian Gulf waiting for the final transaction to take place. In addition, as of September 2018, the year-to-date imports of pharmaceuticals from the EU to Iran fell by 6% year on year. Unit prices increased due to difficulties in making transactions and shipping, suggesting an even sharper drop of around 10% in volumes.

Iran might lose further international partners

So far, India, Turkey, and China have not completely halted Iranian oil imports. However, they are in negotiations with the US administration in some other aspects in their bilateral relations. It is possible that Iran could figure in these talks, and these countries may end up receiving some concessions from the US in return for halting trade with Iran.

For instance, on December 1st US President Donal Trump met China’s Xi Jinping in Argentina to discuss ways to wind down the trade war between the two countries. On the same day, the Chief Financial Officer of Huawei Technologies Co was arrested in Canada at the request of the US administration on charges of bypassing Iran sanctions in the previous rounds of international sanctions in 2013. Amid US-China negotiations, China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) has suspended investment in Iran’s South Pars natural gas project, shortly after the Iranian Oil Minister announced on November 25th that CNPC was officially replacing French firm Total in the world’s largest gas field.

These developments have come despite Iran’s diplomatic efforts to strengthen ties with the East rather than the West, in line with the foreign policy set out by the Iranian Supreme Leader in October. These efforts were demonstrated during the second inter-parliamentary conference on terrorism in December, where Iran invited parliamentarians from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey, Russia, and China. To establish a common ground on defining a new Eastern alliance, Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani called the US economic sanctions against these member countries an act of economic terrorism.

EU-Iran trade is losing momentum

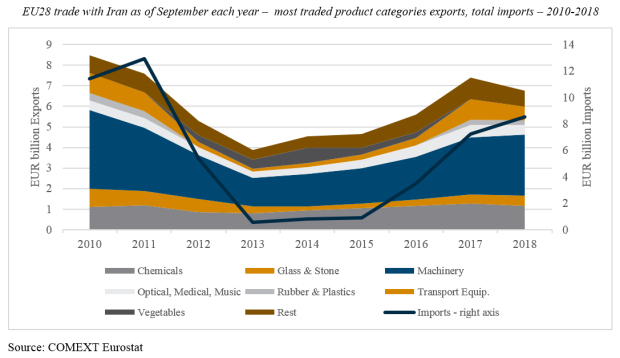

Iran was frustrated that the hoped-for economic dividends resulting from the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) did not materialise, and in particular that trade with the EU did not rise more quickly. Although the JCPOA was signed in 2015, the value of trade between the EU and Iran did not reach its pre-sanctions level (see Figure above). This was owing to inefficiencies in the market due to political risks, but also uncertainties around European support and the potential consequent withdrawal of Iran from the nuclear deal.

Exports from Iran to the EU have increased substantially since 2015. However, 90% of these exports are mineral products. This indicates lack of competitiveness in Iran, and the low quality of products in many other sectors of the Iranian economy. Some in Iran had hoped that the JCPOA would help with quality upgrading, by supporting higher investment by European companies in Iran to boost domestic industrial growth, underpinning technology transfers. This process appears to have at least started: a major category of exports from the EU to Iran in recent years has been machinery (a source of technological transfer), and there has been a clear rise in demand from the Iranian side since 2015. However, this process appears to be now grinding to a halt in line with the new sanctions. Total exports from the EU to Iran have been declining since the first round of new US sanctions came into force in August 2018. As of September 2018, the year-to-date EU exports to Iran fell by 8.6% year on year, while imports from Iran raised by 18%. However, from August to September 2018, total monthly imports into the EU from Iran dropped by 52%. There may be some seasonal volatility, but that would not be enough to explain such big changes from one month to another.

EU should do what it can to help Iran to make the US pressure as painless as possible

While the US is either offering concessions with a tempting allurement to partners and neighbours of Iran, or threatening companies with financial penalties to push the JCPOA to a final collapse, four of the deal’s signatories, namely the EU, France, Germany, and the UK, have yet to play a very important role in implementing the deal. The EU has promised to deliver an account-clearing mechanism via a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), to facilitate trade that enables legitimate financial transactions of Iran with the EU and any other third countries, to bypass the US financial sanctions.

Although this is a new mechanism with many unknowns in its technicalities, it should be implemented very quickly, so that the delays in imports deliveries to Iran and financial returns of Iran’s exported products do not deepen troubles in the Iranian markets of goods and currency, respectively. Otherwise, a sharp dip in Iranian economic activity could have serious domestic consequences, which might even lead to regional security challenges. As we have already outlined, several announcements of Mr Trump to withdraw US from the deal had caused panic in the Iran market since January. According to the latest report by the Central Bank of Iran, between March and May 2018 (first quarter in Persian Calendar Year), Iran’s growth dropped from above 4.6% in the previous year to only 0.7%. Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) shrank by 0.8%, while GFCF in machinery shrank by 5.2%. This indicates the start of a clear slowdown in Iran’s economy triggered by capital flight. Before this mechanism goes into force, the EU needs to give further incentives for Iran to continue talks on other unresolved issues, to reduce uncertainty for investment in Iran.

One major concern for Iran is the case recently taken by the US to the UN to block Iran’s development of ballistic missiles. Iran has legitimate security concerns that might be logical enough to develop its own missiles within a deterrence and defensive policy framework. However, the concerns of all other countries should be also addressed, and a regional arms deal should be designed to provide permanent security guarantees to Iran. Although Europe lacks the military capacity to be capable of enforcing such guarantees, there is one important reason for European countries to at least take the steps forwards: without the EU, Iran will reach only to the East, as mentioned earlier. If Iran establishes a closer alliance with China, Russia, and Turkey, it will be close to impossible to convince the country to make further efforts for better political, social, and economic reforms.

What should Iran do?

Although rapprochement with the US was tested within the JCPOA and appears to have failed, a hard-line Iran will implement conservative policies on citizens that disturb their social interactions and supress their freedom, a society who has been under sanction pressures for many years. A move towards more hard-line policies could induce further social unrest domestically. A better course for the Iranian government would be to counteract US sanctions with appropriate economic instruments (e.g. stabilising the currency market), a strengthening of diplomatic relations with other countries (in particular the EU), and a further opening up of society with inclusive policies such as recent support for allowing the entrance of women into football stadiums.

photo: Iran Grunge Flag, Nicolas Raymond, CC-BY-2.0