Making the best of a bad hand

29 October 2019

North Macedonia has been treated unfairly by the EU, but NATO accession should still bring economic benefits.

by Mario Holzner

image: public domain

- The European Council has again blocked the start of EU accession negotiations for Albania and North Macedonia.

- As we have already argued, this is a big mistake, and risks undermining progress on reform in the region.

- While the negatives are clear, the positives for North Macedonia in now being able to join NATO should not be underplayed.

- Historically, we find that NATO accession brings clear benefits in terms of FDI inflows in CESEE. When committing long-term capital to the region, foreign firms appear to highly value the US security guarantee that NATO membership brings.

At the European Council meeting on 17th and 18th October it was concluded that: ‘The European Council will revert to the issue of enlargement before the EU-Western Balkans summit in Zagreb in May 2020.’ This implies that Albania and North Macedonia will not start their negotiations for EU-enlargement, although they fulfil all the necessary technical requirements and have the support of the European Commission, the European Parliament and most of the EU member states – except France (and in the case of Albania also Denmark and the Netherlands). Under the pretence to first reform the accession process before allowing new countries to negotiate, French President Emmanuel Macron has abandoned the EU’s Balkans promise of 2003. (Although it might be too easy, to put all the blame on President Macron.)

This is particularly depressing for North Macedonia’s Prime Minister Zoran Zaev, who has made great efforts and who has taken a lot of personal risk by fulfilling Greece’s condition of changing the country’s name. He nevertheless remains a steadfast optimist, despite being forced to try his luck in snap elections which have the potential to reverse the whole reform process. In political terms everything was already said and most to the point by outgoing European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, who stated that: ‘I am very disappointed by the result of the EU enlargement discussion. It is a grave historical mistake not to open accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia. A grave historical mistake’. Overall, our assessment from before the General Affairs Council in June 2019 remains valid: further delaying the opening of accession talks sends a terrible signal to the Western Balkans.

NATO matters

However, despite all the justified disappointment, there is also reason to support Prime Minister Zaev’s optimism. Although even starting the process of EU accession is off the table, the same is not true of NATO (accession to which for North Macedonia Greece had also been blocking). The US Senate voted overwhelmingly to ratify North Macedonia’s entry into NATO as the alliance’s 30th member, with 91 Yea’s against only 2 Nay’s (Albania already joined NATO in 2009).

In economic terms, we find that NATO accession is even more important for the country than entry into the EU, at least in the sense that it provides the most serious security guarantee available to foreign investors (i.e. US military support). This then helps countries to attract much needed foreign direct investment (FDI). Given that the economic model of Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE) has been based, from the very beginning of transition, on capital and technology transfers from Western Europe via FDI, this is of utmost economic importance.

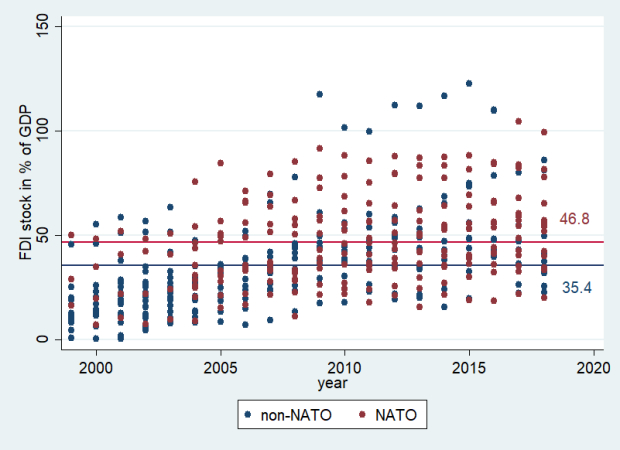

Figure 1 / FDI stock in percent of GDP, 1999-2018, by NATO membership

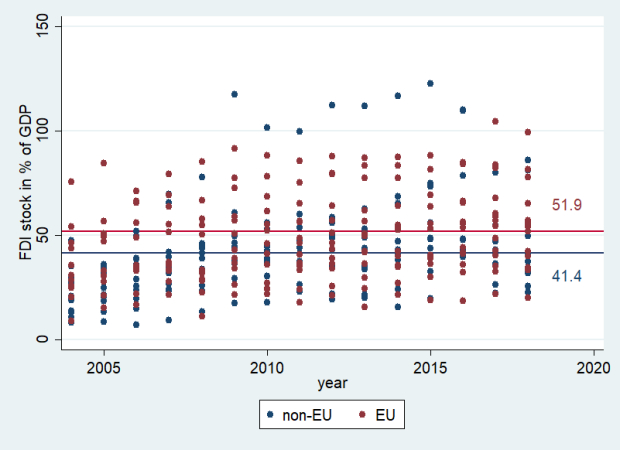

We find that, on average across CESEE, being a NATO member increases the share of FDI in GDP by 11.4 percentage points (Figure 1, using wiiw FDI stock data). This is slightly more (by 1 percentage point) than what can be expected from an EU-membership (Figure 2). In both cases we only compare for the years since the first CESEE countries joined the respective institutions – i.e. since 1999 for NATO and since 2004 for the EU.

Figure 2 / FDI stock in percent of GDP, 2004-2018, by EU membership

However, it could be many other factors that are responsible for these marked differences. We control for these in an econometric model (see full details below).

Our model indicates that NATO membership is much more important for FDI inflows than EU membership, in the years immediately before accession. FDI inflows into CESEE economies picked up significantly three years before NATO accession, in anticipation of the strong security guarantee that this would bring. Presumably, NATO’s Article V—which effectively gives all members US protection in the event that they are attacked—made foreign investors more comfortable about committing their capital to these countries over a long time horizon.

As a result, despite the further delay in the start of EU accession negotiations for Albania and North Macedonia, the direct economic impact of recent developments does not have to be wholly negative. This is especially true for North Macedonia as a soon-to-be-member of NATO. This assumes, of course, that there are no negative political developments and backsliding on reform progress as a result of the unfortunate decision in Brussels.

Econometric analysis

We proceed, for a number of theoretical and methodological reasons, with a time-series cross-sections dynamic specification fixed-effects estimator error correction model (ECM), in order to find out more about the potential determinants of FDI in CESEE. We use wiiw annual data for the period 1990-2018 for 23 CESEE economies. We explain the change in the FDI stock in percent of GDP with the help of the lagged left-hand-side variable as well as the first difference and lagged level of both the log of GDP as well as the log of average gross wage. The first differences should control for the short-run fluctuations, while the lagged level should represent the long-term relationship.

GDP indicates the size of the country’s market and the wage level the production costs. Both should in theory be important motives for FDI penetration. However, our main variables of interest are the dummy variables for NATO as well as EU membership. Here we test a number of lags and leads in order to evaluate the time dimension of the effect, given that in principle FDI could already anticipate NATO and EU membership during the negotiation process or conversely enter the country only after the actual accession, when the respective institutions were already implemented.

It is interesting to note that the coefficients of the control variables GDP and wages are in almost all specifications statistically insignificant. However, in some (e.g. in specification 3 in Table 1), the coefficient of GDP turns significant and surprisingly negative. This implies that FDI was moving rather to smaller markets but not necessarily because of differences in wage levels. This could be related to favourable institutional settings of small open economies – Slovakia might be a case in point.

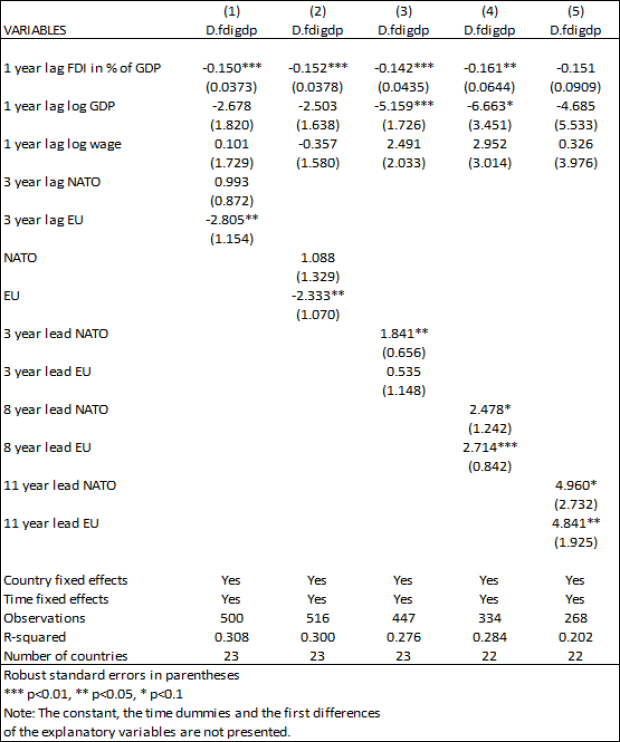

Table 1 / ECM regression results explaining the first difference

of the FDI stock in percent of GDP, 1990-2018, for 23 CESEE economies

It is also fairly surprising that the EU membership dummy variable is negative significant in many specifications, particularly in those where it enters with lags (e.g. specification 1 in Table 1), but also in the case without a lag (specification 2 in Table 1). In the specifications with lead dummies it turns first insignificant (e.g. specification 3 in Table 1) and with more lead years positive significant (e.g. 8 and 11 years before EU accession as in specification 4 and 5 in Table 1). Thus, the EU accession process and not necessarily EU membership was a boost to FDI inflows (also because the CESEE-EU-member countries experienced large FDI inflows already in the early 1990s during the privatisation process). By contrast, NATO membership is in most of the specifications insignificant but turns positive significant only in the case of a 3 years lead dummy variable (specification 3 in Table 1).

Thus, we can conclude that the time dimension is important. NATO accession typically occurred before EU accession and moreover, FDI started to pour stronger into CESEE economies three years before NATO accession (and before that only in the early stages of EU accession negotiations), anticipating the substantial improvement in security issues.