Eastern Europe Coronavirus tracker: Preparing for the worst

31 March 2020

The prospects for the region’s economies are increasingly dire, and many face a 2009-like downturn or worse.

- We assume that the lockdowns in big, Western economies will last for 2-3 months, but that restrictions on economic life will not be fully lifted until the second half of 2021. All will post deep recessions in the first half of 2020.

- We will update our forecasts for CESEE by the end of April as more data becomes available. For now, we retain our ‘best case’ scenarios for negligible or slightly negative growth across CESEE this year, but acknowledge that the prospects of this are increasingly slim.

- Our new baseline scenario is likely to project that CESEE countries will on average register full-year contractions in 2020 of 3-5%. A ‘worst case’ scenario with contractions of 10% or more is however very possible for the non-EU member states of the region (and possibly even some of the EU member states).

- A huge range of indicators are relevant in trying to gauge the economic impact, but we are particularly focused on the quality of public healthcare systems and the space for a fiscal response. We believe that the 2004 EU joiners are in a much better position than the rest of CESEE (including the 2007-13 joiners).

- As we wrote last week, digitalisation in CESEE will get a huge push from the current developments. Countries already relatively advanced (the 2004 EU joiners and Russia) are in a potentially good position to profit from this.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Tracking the virus in CESEE: what we know so far

- Economic impact on CESEE: How bad could it get?

- Initial signs and policy responses

- Country impacts: key factors to watch

- What next?

Introduction

The Coronavirus is spreading rapidly in Europe. There is huge uncertainty and a lot that we don’t know. However, there are also some things that we can say. Our key assumptions about the fallout from the coronavirus for the global and European economies at present are the following:

- Lockdowns in Europe will last 2-3 months, and then be gradually relaxed. The quality of countries’ healthcare systems, and the speed with which mass testing can be implemented, will be central in determining how long full restrictions need to be kept in place.

- The big European and global economies will record deep recessions in H1 2020. As restrictive measures are relaxed after a few months, some kind of recovery will materialise, but this will be very sluggish until the vaccine is widely available (most likely in the second half of 2021). Countries that are able to roll out mass testing, enact huge fiscal stimulus, or those that have particularly high levels of capacity in the (state) healthcare system will perform better in economic terms.

- Wealthy western countries will be able to borrow huge amounts of money to enact large-scale fiscal stimulus, but many emerging markets (including in Eastern Europe) will not have this option. A financing squeeze will require more restrictive fiscal policy, exacerbating the downturn. The role of the IMF and other international lenders will be crucial in mitigating the worst of the downturn in emerging markets.

- The big guns (China, the US and the EU/euro area) will eventually do ‘whatever it takes’ in fiscal and monetary policy to prop up the global economy. However, there are risks especially associated with the US (removal of expertise in key positions since President Trump took office) and the euro area (the usual North-South tensions over fiscal sharing). This is where we are most uncertain, and also most worried. Even if big amounts of money are pledged, there is a risk that this cash will not find its way to the people and firms who really need it. The ‘ideal’ policy response is to provide cash to small and medium-sized firms (allowing them to keep on staff) and to maintain liquidity in the banking system.

Tracking the virus in CESEE: what we know so far

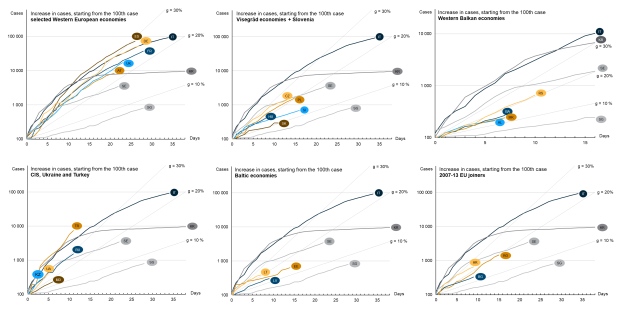

The Coronavirus has spread more slowly to Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE) than in Western Europe so far. Based on growth rates, cases in most of CESEE do not seem to be growing as quickly as in Italy (charts 1; here we loosely follow the methodology established by the Financial Times here). This is good news, but could reflect differences in levels of testing, and so we will need to wait for more data before making concrete assessments. Even at these levels of growth in cases, however, the impact on CESEE economies will be profound.

Charts 1 (click to enlarge):

Economic impact on CESEE: How bad could it get?

This is a crisis for CESEE without parallel in the post-Communist era. Trying to quantify the full economic impact is therefore impossible at present, and we will wait another month before publishing updated forecasts. We wrote last week that this will be the worst year for the region’s economies since 2009. However, for many countries, it may well end up being substantially worse than that. Our best guess at present is that the average contraction for 2020 in CESEE will be in the range of 3-5%, with a ‘best case’ being growth of barely above zero for most (see our analysis from last week here), and the ‘worst case’ feasibly a contraction of 10% or more for some countries. The ‘best case’ would involve a rapid containment of the virus, rollout of mass testing in the next couple of months, and a huge and coordinated policy response across Europe. We are naturally increasingly sceptical that all of these conditions will be met. The ‘worst case’ would involve countries losing access to external finance and a collapse of the healthcare system, requiring drastic fiscal austerity and severe restrictions being placed on economic life for much longer than currently envisaged.

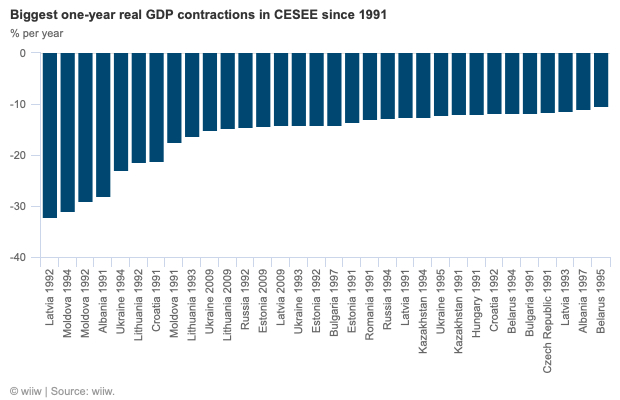

Past data can give us at least some quantitative sign-posts about how deep the downturn could be, and which countries could be most affected. The CESEE region has faced three main crises in the post-Communist era: the initial transition recessions of the early to mid-1990s; the Russian financial crisis of the late 1990s; and the global financial crisis of 2008-09. The biggest declines in GDP in the post-communist era were around 30% in the early 1990s (with all the usual caveats about data quality from that time; chart 2). In the most recent era, the worst downturns were in 2009, when Ukraine and the three Baltic states contracted by 14-15%. We identify 32 instances where a CESEE country has registered full-year negative real GDP growth of more than 10% since 1991. Some countries are especially highly represented in this list: Moldova, the Baltic states and Ukraine. This likely reflects either chronic mismanagement of the economy and institutional weakness (for example Ukraine) or the vulnerabilities associated with being a very small and highly open economy at a time of international economic crisis (the Baltics). By contrast, most of the Western Balkans, Turkey and a large number of EU-CEE countries do not appear on this list at all, implying a potentially higher degree of resilience.

Chart 2:

Initial signs and policy responses

We have very little data to go on to measure the impact so far (for China and some Western economies, the FT has some excellent data here), but to start with we have compiled numbers of consumer and business confidence (where available and comparable) and exchange rates. The first will give us an indication of the domestic reaction, whereas the latter will reveal a mixture of domestic and international responses.

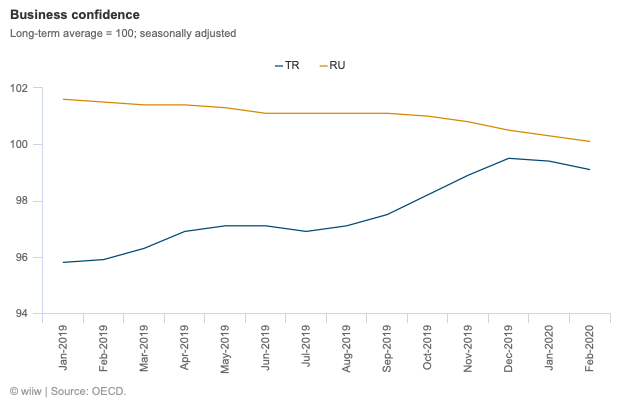

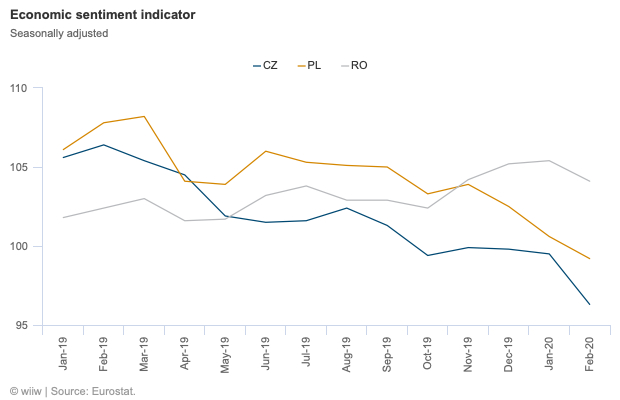

Confidence: The latest data that we have (charts 3) only capture the very beginning of the Coronavirus impact, and so we expect these indicators to get substantially worse in the coming months. Nevertheless, data for the early months of 2020 already show a clear downward trend in many countries.

Charts 3:

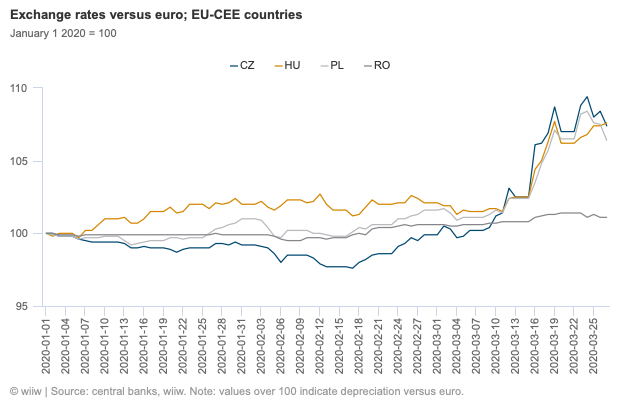

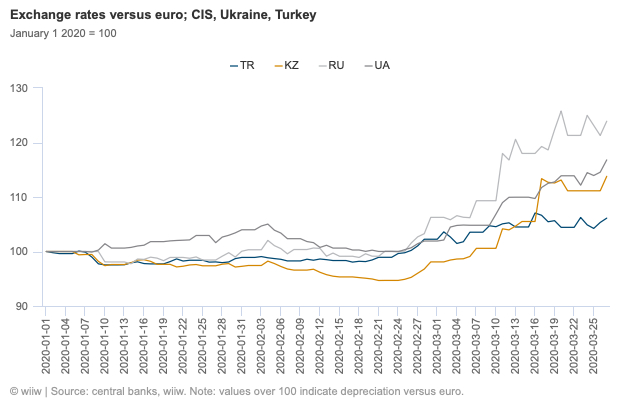

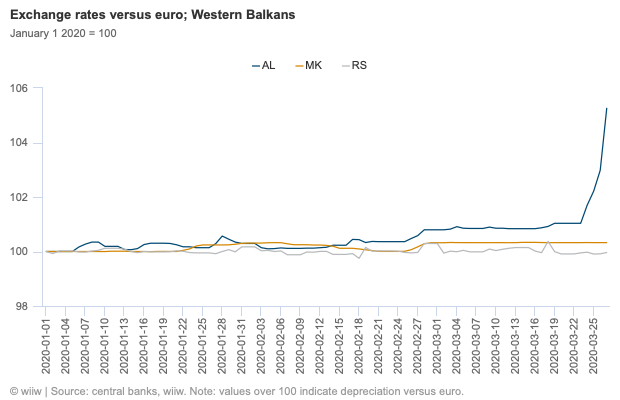

Exchange rates: Here we see a broad-based sell-off, albeit with clear differentiation (charts 4). Since the beginning of the year, almost all of the main floating regional currencies have depreciated against the euro. The sell-off has been generally less in the EU member states than the rest, albeit still quite substantial for most. Among non-EU member states, notable declines have been registered for the currencies of Kazakhstan (11%), Ukraine (15%) and especially Russia (25%). The Turkish lira and the Serbian dinar have been more resilient so far (the latter in particular helped by central bank interventions) but this is not guaranteed to last.

Charts 4:

So far, policy responses differ across the region. We have compiled a table with the key measures, which we plan to update weekly. This includes monetary, fiscal and social distancing measures. So far, we identify the following broad groups (with the caveat that this is a rather inexact science at present):

- Big fiscal measures, big social distancing: Croatia.

- Big fiscal measures, limited social distancing: the Baltic states and Kazakhstan.

- Medium fiscal measures, big social distancing: Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovenia.

- Small fiscal measures, big social distancing: the Western Balkans, but also (to varying degrees) Hungary, Turkey and Ukraine.

- Mostly business as usual: Belarus and Russia (the latter now belatedly changing).

- Few details: Slovakia.

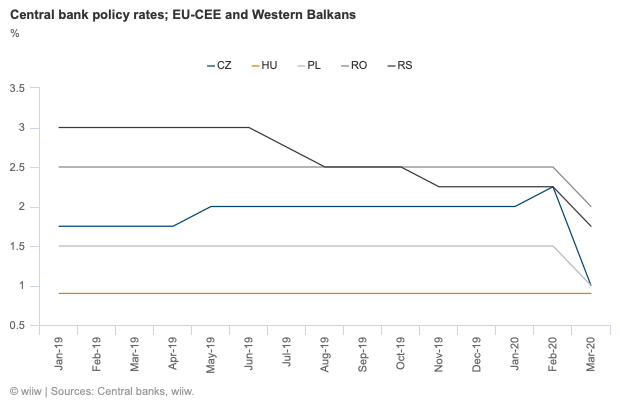

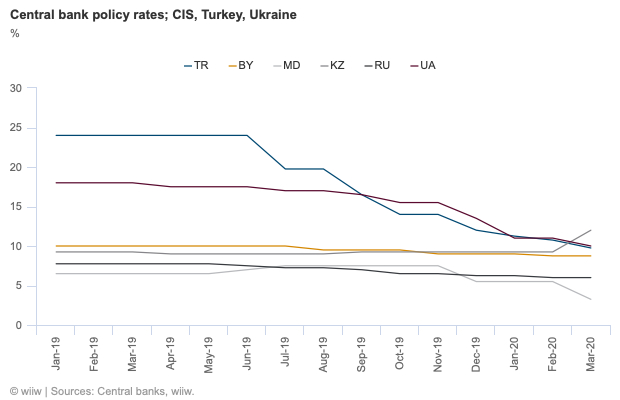

Monetary authorities have already reacted in most places where this is possible, in order to stimulate the economy via lower policy rates and to inject liquidity into the banking sector. However, Kazakhstan already had to tighten policy in response to the oil price shock and depreciatory pressures on the tenge; this might be a sign of things to come for other countries in CESEE as the virus spreads. In other countries (i.e. Serbia, Russia and Ukraine) the central bank is trying to combine a defence of a weakening currency with measures to increase liquidity in the domestic banking sector.

Charts 5:

The key policy lever in this crisis will be on the fiscal side. Here, most of what has been announced so far is quite modest, and where the plans are more ambitious, we question how they will be financed. We estimate that the biggest measures are in Lithuania (10% of GDP), Estonia, Latvia and Croatia (all around 7%). Some CESEE countries will ultimately be able to pursue a strong counter-cyclical response, but others will be severely constrained (see longer fiscal section below). As the table shows, many countries are already receiving international support (from international organisations, the EU, or friendly countries such as Russia), but nowhere is this significant as a share of GDP.

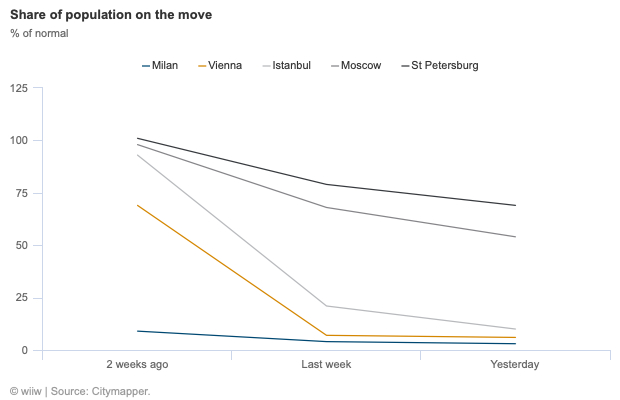

For social distancing, fairly stringent shutdowns (i.e. similar to those in Austria) are in place across many counties. However, some have opted for a looser approach so far. The former will suffer more than the latter in economic terms initially, but if the virus spreads and puts too much strain on the healthcare system, these countries that have so far resisted more stringent measures may be forced to change. One illustration of the different approaches can be seen by comparing data for the share of the population ‘on the move’ in Milan, Vienna, Istanbul, St Petersburg and Moscow (chart 6; unfortunately data for other major CESEE cities are not available). These data use public transport data to show the number of people on the move as a share of the normal total. In Istanbul, the trends and levels are quite similar to Vienna, whereas in Russia a much higher share of people continue to move around the two main cities.

Chart 6:

Country impacts: key factors to watch

In terms of trying to understand the impact that the Coronavirus will have on the economies of CESEE, there are hundreds of indicators that we could use. Our view though is that two things are really crucial in terms of how bad the economic fallout will be. First, the capacity of the healthcare system to deal with a public health crisis (as long as healthcare systems are under severe strain, it will be hard for governments to loosen restrictive measures on economic life). Second, the fiscal space that the state will have to enact counter-cyclical measures (some countries will be able to throw a lot of money at the problem, whereas others will probably be forced into damaging pro-cyclical fiscal austerity). In addition to these two factors, we also here consider various macroeconomic indicators to determine how bad the impact on individual countries could be.

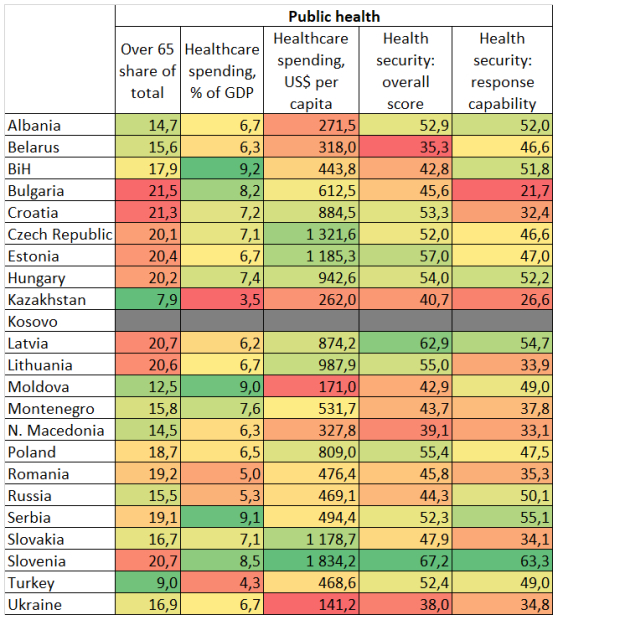

1. Public health factors

The state of the healthcare system in general, and its ability to manage a public health crisis in particular, will be key (table 1). The Global Health Security (GHS) Index shows a huge range in CESEE. For the overall score, Slovenia and Latvia score better than Austria. However, the CIS, Ukraine and parts of the Western Balkans score much worse. In terms of response capabilities, EU member states such as Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia and Lithuania also score very badly. Interestingly, Turkey scores well on both of the GHS indicators used here. In general, the capacity of healthcare systems is linked to the countries’ wealth; per capita healthcare spending is generally much higher in the countries than joined the EU in 2004 than anywhere else in CESEE, and so all else being equal we expect the region’s wealthier countries to cope better. Countries with older populations may also struggle more, as those over 65 are thought to be at much greater risk from the virus (this can be seen in Italy).

Table 1:

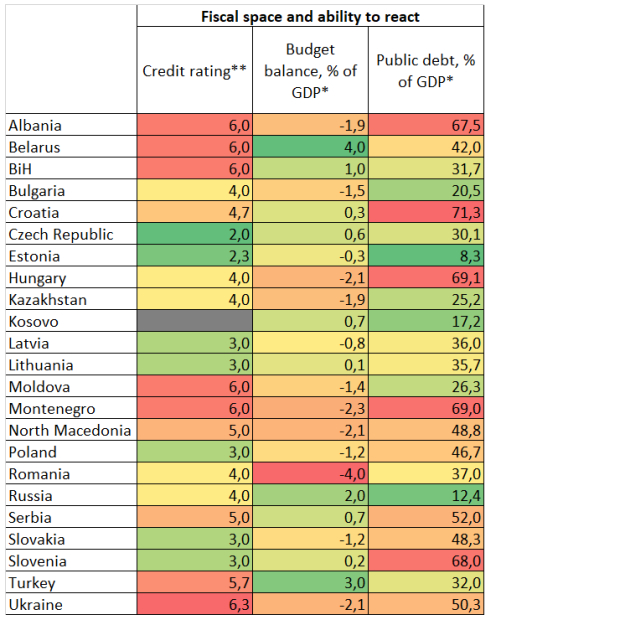

2. Fiscal factors

Countries’ fiscal deficits will widen substantially this year, reflecting a combination of extra state outlays (for example of healthcare, or support for businesses and the unemployed) and deep recessions. The wall of liquidity emanating from the big central banks will certainly help CESEE countries to find the extra financing that they will need. However, at least some are likely to struggle to access international capital markets as the situation deteriorates and foreign investors lose confidence. Key here will be investor sentiment towards these countries in general (proxied by existing credit ratings; see table 2) as well as the state of the public finances in general. Many will turn to the IMF, but this money will come with stringent conditions. Overall, we think the EU member states have a much better chance of riding this out, but we are less sure about those that joined the bloc in 2007 and 2013. Countries in the CIS, Ukraine, the Western Balkans and Turkey have the worst credit ratings. Capital flight is a serious risk for most of non-EU CESEE, and a genuine risk for even most of the EU member states.

Public debt loads are not especially high anywhere in the region, and have generally fallen since the crisis, but are most elevated relative to GDP in Albania, Croatia, Hungary, Montenegro and Slovenia. It is quite unlikely that Slovenia could face a serious squeeze on its external financing, and the situation would also have to deteriorate materially for this to happen to Hungary. However, Croatia, Albania and especially Montenegro could all be vulnerable to external financing pressures as their fiscal deficits widen (it is a particular worry that these three countries are also the most tourism dependent; see below). Romania is also a country to keep an eye on, with its large twin current account and fiscal deficits of recent years having made many investors wary. Over the course of the crisis, we expect public debt/GDP loads for the countries of CESEE to increase substantially, and to stay at historically high levels for many years. The global financial crisis provides a clear example of how big recessions and fiscal deficits (as well as currency devaluations, in cases where a large part of the public debt is denominated in foreign exchange) can push countries’ debt/GDP ratios upwards very quickly. Between 2007 and 2010, public debt/GDP loads increased by over 20 percentage points in many CESEE countries (including almost 40 percentage points in Latvia).

Table 2:

* 2019 data;

** 1 = prime, 2 = high grade, 3 = upper medium, 4 = lower medium, 5 = non-investment grade speculative, 6 = highly speculative, 7 = substantial risks. Scores represent averages of long-term foreign currency sovereign ratings by Moody's, S&P and Fitch.

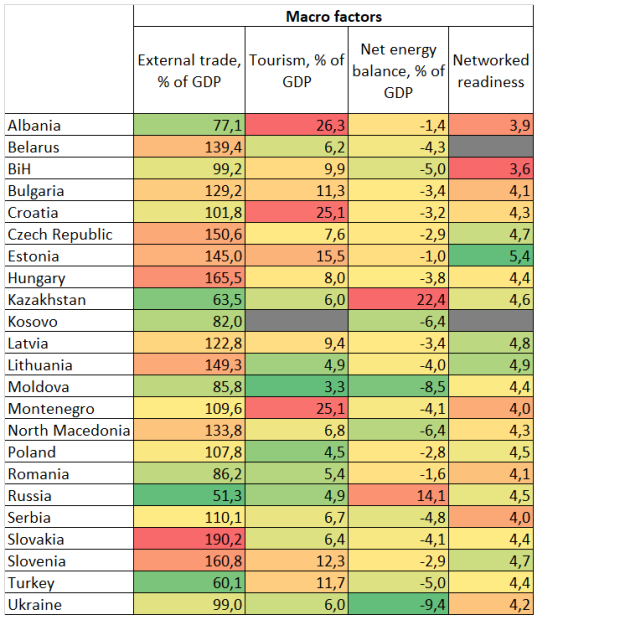

3. Macro factors

The true macroeconomic channels of contagion remain difficult to gauge. Here we focus initially on four areas that we think will be important: trade openness, dependence on tourism, net energy balance and networked readiness (table 3).

Trade openness: CESEE is in general full of small, open economies (Turkey and Russia are the major exceptions). Many assume that the trade-dependent Visegrad countries will be hardest hit in CESEE by the Coronavirus, thanks to the huge disruptions to global trade that we already see. Slovakia is the most open economy in CESEE, followed by Hungary, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Estonia. However, we are not so convinced that trade openness will be the main determining factor of the economic fallout in the medium run (we will deal with this in more detail in a forthcoming analysis). The key economic fallout will be on domestic demand thanks to huge restrictions on economic life, and as Asia recovers, trade-dependent economies in CESEE may actually receive a timely boost. The small, open economies of central Europe are also closely integrated with Germany, which is planning a sizeable fiscal stimulus (with presumably some positive spill-overs for neighbouring countries).

Tourism dependence: This sector has already been hammered, and if the lockdowns continue into the summer (as looks likely) the situation will become quite desperate for tourism-dependent economies. In CESEE three countries in particular stand out: Croatia, Montenegro and Albania. However, as we have written regularly in our country coverage of the last few years, tourism has been growing quickly in many others parts of CESEE in recent years, and as a result the fallout will be quite widespread. In a further five countries—Bosnia, Turkey, Bulgaria, Estonia and Slovenia—tourism accounts for around a tenth of the economy.

Net energy balance: The oil price has collapsed and a recovery is not in sight. This will hit both Russia and Kazakhstan very hard, although both have substantial reserves to cushion the blow. All other CESEE countries are net energy importers, although past experience shows that the losses of exporters will not necessarily translate into gains for the importers. This may be especially true in this instance, with the likely collapse in consumer confidence meaning that the oil boost to real incomes is saved rather than spent.

Networked readiness: Across Europe, large parts of professional life are being moved online. The ease and speed with which this can be done, and the quality of the infrastructure that supports it, will be key to determining how countries fare. As we have previously discussed, digitalisation is an opportunity for CESEE, but the extent of ability to take advantage of this varies hugely. Famously, Estonia leads the way, and compares well with the Western European frontrunners in this regard according to the World Economic Forum’s Networked Readiness Index. The other Baltic states and Slovenia also perform quite well. Interestingly, Russia and Kazakhstan have relatively good scores by CESEE standards. The Western Balkans appears particularly weak here.

Table 3:

What next?

We plan to publish an updated set of macroeconomic forecasts for all 23 countries in CESEE in the second half of April. Until then, we will compile weekly updates tracking the numbers of cases and policy responses in CESEE, and publish additional commentary (including policy suggestions) on our website.