Outward migration from EU-CEE is slowing

13 December 2017

Workers will continue to move from EU-CEE to Western Europe, but Brexit and better prospects at home will keep the numbers lower than in the last decade.

By Isilda Mara.

Photo: Lars Plougmann, CC-BY-2.0

- High unemployment rates, easier access to EU15 labour markets, and the prospects of much better wages, have driven strong outward migration from EU-CEE to the wealthier parts of the bloc over the past decade.

- Persistent negative net migration from EU-CEE, but also improved growth has contributed significantly to a sharp reduction in unemployment rates across most of the region. As a result, shortages of skills and workers are starting to emerge.

- This constellation of factors together with strong growth has led to rapid wage increase in some countries, including the Baltics, Romania and Bulgaria.

- Recently the pace of outward migration from EU-CEE countries has been slowing down, and this could continue. However, the west-east gap in incomes is still substantial, and will continue to act as an important pull factor for workers from EU-CEE.

Immigration from EU-CEE to the EU15 has been driven by three key factors

Elevated unemployment at home in the past, and the prospect of higher wages in the west, have been key drivers of outward migration from EU-CEE. However, EU enlargement was also an important determinant. The years immediately after joining the EU or the end of the transitional period (2+3+2) are the ones when the peak of emigrants/immigrants is observed. This was confirmed in 2004 and 2007 when EU-CEE countries joined the EU, but also in 2011-2012 or 2013-2014 when all EU15 countries granted free labour market to the new joiners. Several studies which have dealt with migration from EU-CEE countries have confirmed a hump shape of net migration trajectory for the first years following transitional periods or EU-enlargement (Landesmann et al [2013], Vidovic and Mara [2015]).

Sharp drop in unemployment rates and closer to full employment

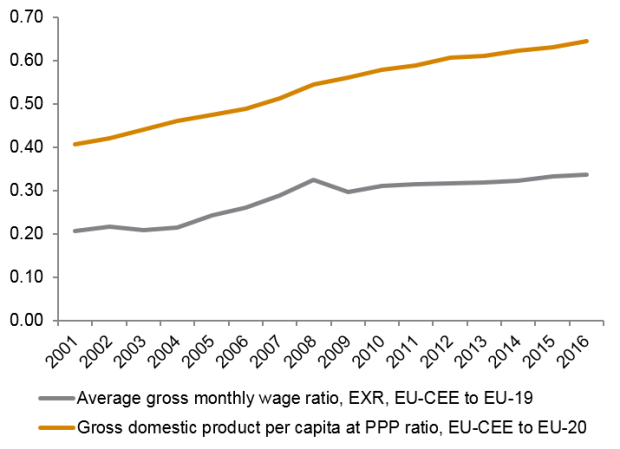

In 2016, the unemployment rate in EU-CEE dropped to 7.6%, down by 4.5 percentage points compared with 2010. Unemployment rates in countries such as the Czech Republic (4%) and Hungary (5%) indicate that they are close to full employment. Across much of the region, employment rates and wages have been rising and the gap in GDP per capita terms between the CESEE and EU-15 countries has been closing at the level of 69% (see the wiiw Handbook of Statistics 2017 and Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: The ratio of GDP per capita and nominal average gross monthly wages in EU-CEE vs EU-19 levels.

Skills and labour shortages are emerging

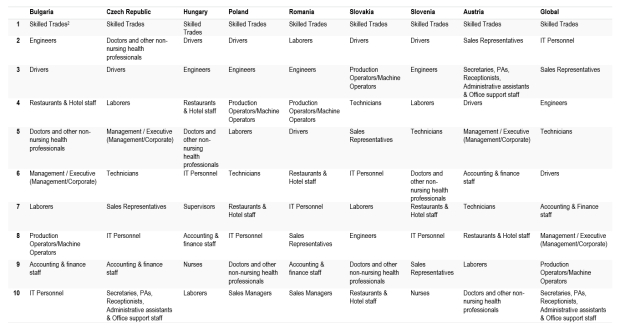

During the last decade, because of high negative net emigration rates from EU-CEE countries, birth rates have declined and populations have shrunk, a phenomenon which is expected to continue in the future. More recently, unemployment rates in the region have been pushed down by positive employment trends in EU-CEE and continued negative net migration rates. These developments have resulted in the emergence of skills and labour shortages in parts of EU-CEE. In EU-CEE countries businesses face difficulties in finding both high and low-skilled employees (see Table 1 below). In line with overall global trends, EU-CEE countries are struggling to find engineers, IT professionals and technicians, but also skilled trade workers and drivers. As well as large-scale migration, businesses are facing skill shortages because of technological progress.

The hardest occupations to find

Source: Talent Shortage Survey 2016-2017

Pace of outward migration from EU-CEE is slowing, but earnings differential remains an important pull factor

Push factors for emigration from EU-CEE countries are likely to be less strong in the coming years. The economies of EU-CEE countries are performing well and are expected to continue to do so in the medium term (see for example wiiw’s Autumn 2017 Forecast Report). Labour market and employment opportunities in the region have improved, reflected by higher wages and participation rates in employment. In addition, pull factors might be not as strong, because gaps in GDP per capita, gross earnings and unemployment rates have narrowed.

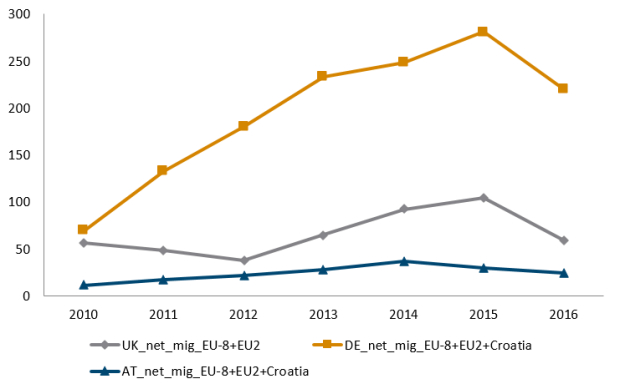

These trends are visible in some recent data. In 2016 Germany and Austria both recorded a 20% year-on-year decline in net immigration from EU-CEE (220,000 and 24,000, respectively). Meanwhile in the UK, in the year to March 2017 net immigration from EU-CEE halved to 50,000, although Brexit makes this a special case. Net immigration from EU-CEE slowed during this period owing to the Brexit-driven deteriorating economic situation in the UK, as well as migrants’ uncertainty about their future employment and residency rights.

However, while the pace may have slowed, net outflows of workers from EU-CEE to the EU-15 remain high, and this is likely to continue. At an individual country and regional level, differences in income levels remain pronounced. This likely explains why outward mobility from EU-CEE is persisting, albeit at a slower pace due to better prospects at home.

Blessing becomes a curse

Overall, outward migration from EU-CEE has been a blessing for the labour markets, which in the past have been tormented by high unemployment rates. However, more recently outward mobility has turned into a curse, being one of the main causes of labour and skills shortages. While outward mobility from EU-CEE has slowed down (and is likely to remain at lower levels in the future), it is still premature to talk about significant return migration.

Figure 2: Net migration from EU-CEE to selected destination countries, 2010-2016