Phasing out coal?

image credit: unsplash.com/Андрей Курган

-

A shift away from coal in favour of sustainable energy has been promoted by the EU Commission as an essential step towards achieving climate neutrality by 2050.

-

But the energy crisis now unfolding in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine and the use of locally extracted solid fossil fuels as an alternative to natural gas could render the EU’s ambitions unrealistic.

-

EU countries should therefore maintain their phase-out plans and show greater solidarity with the regions and communities likely to be most affected.

The European green deal and the ambition of climate neutrality

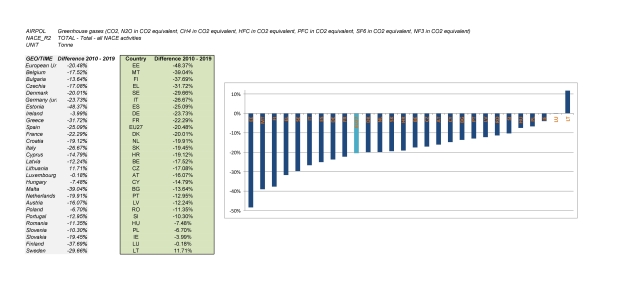

Launched in December 2019, the European Green Deal was introduced as the EU’s roadmap to transform its economy into ‘a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy’ and achieve climate neutrality – i.e. no net emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) – by 2050 (European Commission, 2019). At the same time, it is supposed to safeguard economic, social and territorial cohesion, in the sense that ‘no person and no place [should be] left behind’. In practical terms, the EU’s ambition to become the first climate-neutral continent, in particular through the decoupling of economic growth and resource use, should not come about at the expense of economic convergence between the older and the newer member states. That surely represents a major challenge, as the EU-CEE countries, which already show lower levels of economic development than their Western counterparts, also lag behind the rest of the EU in their efforts to reduce GHG emissions: GHG emissions stemming from economic activities decreased in the EU as a whole by 20% between 2010 and 2019, but the figure was lower in all EU-CEE countries (bar Estonia) – and in the case of Lithuania, GHG emissions actually increased by 12% (Figure 1).

Figure 1 / Change in GHG emissions in EU countries between 2010 and 2019 (%)

Note: total of all NACE economic activities. Source: Eurostat, Air emissions accounts by NACE Rev. 2 activity, EU27, indicator ‘env_ac_ainah_r2’, 2010-2019 data.

Coal phase-out commitments (before the war in Ukraine)

An important step towards GHG emission reduction and climate neutrality is, of course, to move away from polluting sources of energy – in particular, fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas, which emit considerable amounts of GHGs when burnt – to more environmentally friendly sources, and in particular renewable energy. Of all the sources of energy, coal is widely considered to be the ‘dirtiest’ in terms of GHG emissions, and is thus one of the main targets of the European low-carbon transition policy. As a matter of fact, gross available energy produced from solid fossil fuels (i.e. hard coal, brown coal and coal products altogether) decreased by 30% between 2010 and 2019 in the EU.1 However, solid fossil fuels still accounted for 16%, 22% and 11% of the EU’s gross electricity production, gross heat production and gross available energy, respectively, in 2019.2 At that time, there were around a hundred coal mines still operating in the EU, a quarter of them in Poland (European Commission, 2021). While the majority of EU countries have decided to retire existing coal-fired power stations and/or withdraw planned investment in such capacity (i.e. ‘phase out coal’), other countries (including Poland) have made no such commitments, or have agreed only partial phase-out plans without any fixed timeline.

Figure 2 / Coal phase-out plans in EU member states before the war in Ukraine

Source: European Commission, Coal regions in transition

(https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/oil-gas-and-coal/eu-coal-regions/coal-regions-transition_en)

Therefore, the EU has pledged to back coal phase-out plans made by its member states by providing tailored support to the most affected regions, industries and communities. One important instrument designed by the European Commission for this purpose is the Just Transition Mechanism. This aims to help national and regional authorities identify and deliver solutions in the context of the transition to a low-carbon economy. It consists of three pillars: the Just Transition Fund (JTF), the InvestEU ‘Just Transition’ scheme and the Public Sector Loan Facility. In particular, the JTF is designed to ‘alleviate the socio-economic costs triggered by climate transition, supporting the economic diversification and reconversion of the territories concerned’ by disbursing EUR 19.2bn (in current prices), primarily in the form of grants.3 Those territories include a large number of so-called ‘coal regions’ across the EU, where coal mines and/or coal power plants are still operating.

Coal regions and the challenge of decarbonisation

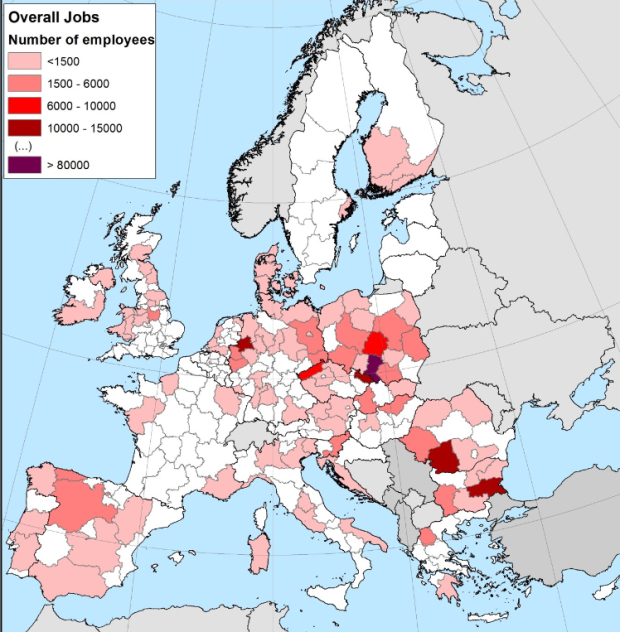

Coal regions in Europe are very diverse, in terms of both their dependence on coal for employment and industrial output, and their potential for economic reconversion. In some regions, coal mines and coal power plants provide tens of thousands of jobs locally; in others, just a few hundred (European Commission, 2018). Although coal-reliant employment can be observed almost everywhere in the EU, it is noteworthy that regions of Germany, Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria contain the largest concentrations of these jobs.

Figure 3 / Total number of jobs in coal power plants and coal mines in EU and UK regions

Source: European Commission (2018).

Likewise, some regions exhibit a high potential for the deployment of clean energy technologies (such as wind, solar photovoltaics, bioenergy and geothermal energy), and hence for new job creation. In other regions, that potential is severely limited by geography. A study carried out by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre assesses the ‘decarbonising employment potential’ of coal regions, based primarily on their technical potential for clean energy sources (i.e. the prospective power capacity of clean energies, taking system, topographic and land-use constraints into account) and their technical energy-saving potential associated with the renovation of residential housing stocks (European Commission, 2020). The study shows that Central and Eastern European regions overwhelmingly demonstrate a low ‘decarbonising employment potential’, as the potential job creation resulting from clean energy and energy efficiency activities would not compensate for the jobs lost if coal mines and coal power plants were to close. There, more than in other parts of Europe, decarbonisation represents a socioeconomic challenge. This is even more problematic as those regions already face a number of other socioeconomic challenges, with GDP per capita levels, innovation potential, competitiveness, institutional quality, etc. all lower than the EU average. Furthermore, the likelihood that their low-cost advantages and their returns on infrastructure investment will decline over time adds to the risk that these regions will fall into the so-called ‘development trap’ (European Commission, 2022).

Russion gas dependence and Europe's new predicament

The war initiated by Russia in Ukraine and the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s retaliation against Western sanctions have served as a wake-up call for the EU, leading it to reconsider its energy policy. More than six months after the start of the war – and despite the EU’s swift response to the energy market disruptions (see, for instance, the REPowerEU plan, which prepares the ground for a massive and rapid reduction in dependence on Russian fossil fuels) – a few European countries are still heavily dependent on Russian gas, and many are dreading the approaching winter. As estimated by the International Monetary Fund (2022), a full shut-off of Russian gas supplies would have significant repercussions for all European economies, first and foremost Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia, Italy and Germany, but also Austria, Romania, Slovenia, Croatia and Poland. Indeed, many of these countries are effectively disconnected from Western gas transmission networks.

It therefore comes as no surprise that the gas supply cuts by Russia, combined with soaring energy prices, have already prompted many EU countries (such as Germany, Italy, Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Romania and Greece) to consider the possibility of keeping the coal mines open for longer than planned – and indeed of reopening closed mines to ensure their energy security. If resorting to coal as a substitute for Russian fossil fuels appears to be the most cost-effective solution (at least in the short term), then the widely shared aspiration to become a coal-free economy could rapidly be shelved. As a result, the EU could soon be faced with a dilemma: to become independent of Russian fossil fuels by 2030 (or even earlier), as announced by the European Commission on 8 March 2022; or to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels), as advocated in the European Green Deal.

To avoid this conundrum, EU countries need to step up, coordinate and balance their efforts to phase out fossil fuels – whether imported or extracted locally – and invest in clean energy-production technologies. This would also require a high level of solidarity both between and within countries, as those regions most reliant on coal as a source of energy and employment are mainly those with a low decarbonising employment potential, those lagging behind the rest of the EU in their socioeconomic development and capacity to invest in new technologies, and those whose national governments are still most susceptible to a Russian gas supply shut-off. Otherwise, the outlook for European economic, social and territorial cohesion could be grim, with many people and places actually left behind in the race to (sustainable) energy security. Meanwhile, the EU East–West convergence process could be dramatically slowed, if not halted.

REFERENCES

European Commission (Joint Research Centre) (2018), EU Coal Regions: Opportunities and challenges ahead (EUR 29292 EN). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission (2019), The European Green Deal sets out how to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, boosting the economy, improving people’s health and quality of life, caring for nature, and leaving no one behind. Press release, Brussels, 11 December.

European Commission (Joint Research Centre) (2020), Clean Energy Technologies in Coal Regions: Opportunities for jobs and growth – deployment potential and impacts (EUR 29895 EN). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission (Joint Research Centre) (2021), Recent Trends in EU Coal, Peat and Oil Shale Regions (EUR 30618 EN). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission (Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy) (2022), Cohesion in Europe towards 2050: Eighth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

International Monetary Fund (2022), Natural Gas in Europe: The potential impact of disruptions to supply, SUERF Policy Brief No. 412, September.