Q2 GDP data show that EU-CEE is still growing at a healthy rate

16 August 2017

Supportive domestic and external factors will continue to drive growth, but momentum could slow a bit in the second half of the year. By Richard Grieveson.

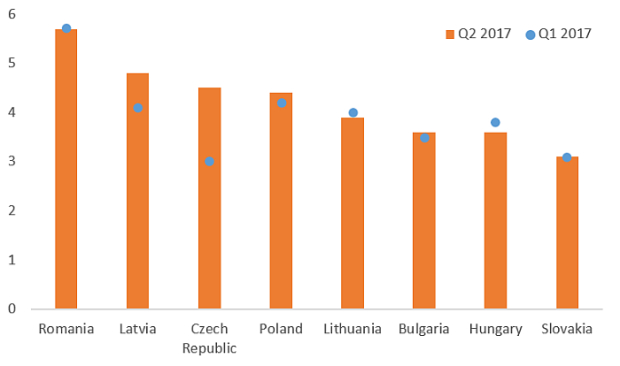

A host of flash estimate GDP data released by Eurostat and national statistics offices on August 16th showed that the economies of EU-CEE had another highly impressive quarter of growth in April-June. In seasonally-adjusted terms, growth strengthened in relation to Q1 from already elevated levels in the Czech Republic, Latvia, Poland and Bulgaria. In Romania and Slovakia momentum was unchanged relative to the previous three months, while in Lithuania and Hungary it slowed slightly. Data for the other EU-CEE economies—Slovenia, Estonia and Croatia—are not yet available.

Domestic and external conditions remain broadly supportive

As we outlined in our Spring Forecast, we see an important confluence of supportive factors for EU-CEE growth, particularly strong domestic labour markets, still-weak inflation (with a positive knock-on effect for private consumption), and a pick-up in private and EU-financed investment. All of these factors appear to have been important in driving Q2 growth. In addition, as we have long argued, the potential for political risk shocks from big elections in Western Europe in 2017 were overstated. We were always sceptical that populist parties offered a truly serious threat in elections in the Netherlands, France and Germany (if any had won, this could have had fairly serious implications for EU-CEE countries).

However, perhaps the most significant driver of growth has been external, particularly for the more open manufacturing-oriented economies in the Western part of EU-CEE. The larger economies of Western Europe are currently undergoing an impressive cyclical upswing. German GDP rose by 2.1% year on year in Q2, the fastest rate since 2014. Meanwhile the Italian economy expanded by 1.5% year on year, its highest level since 2011. These two economies are particularly important for many countries in EU-CEE as a source of demand.

Momentum may be starting to flag somewhat

We had expected the robust growth numbers recorded in January-March to continue into Q2. Moreover, there are plenty of reasons to think that the second half of the year will also be strong. Domestic factors, particularly tight labour markets and rising EU-financed investment, continue to look supportive. Meanwhile, in the most eastern parts of EU-CEE, where agriculture tends to play a relatively important role in the economy, the latest data indicate strong harvests this year. We may again revise up our growth forecasts for at least some of the countries in EU-CEE in our upcoming Autumn Forecast report.

However, while growth should continue at a healthy level, GDP in the third quarter of the year may be less impressive than in January-June, with high frequency indicators suggesting that momentum could be flagging, at least in some countries. Poland’s manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) fell to 52.8 in July. While still in expansionary territory (anything above 50 indicates positive growth), this was nevertheless an eight-month low. Respondents reported more moderate growth in production, new orders and employment. In the Czech Republic, the manufacturing PMI in July fell to its lowest level so far in 2017, driven by softer sentiment in output and new orders. Meanwhile in Hungary, the July PMI fell to 54.2, below its average of 54.6 recorded for the last three years.

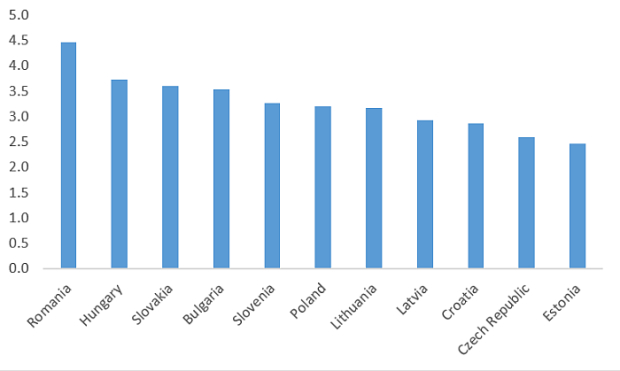

Convergence on track

We think that the outlook for growth in EU-CEE during our three-year forecast period is fairly positive. While the current very strong growth rates are unlikely to be maintained, the region should remain on a relatively healthy track. We forecast real GDP growth rates in 2017-19 ranging from 4.5% for Romania to 2.5% for Estonia. All are likely to be well above the euro zone level (the European Commission projected growth of 1.7% and 1.8% in 2017 and 2018, respectively, in its most recent forecast).

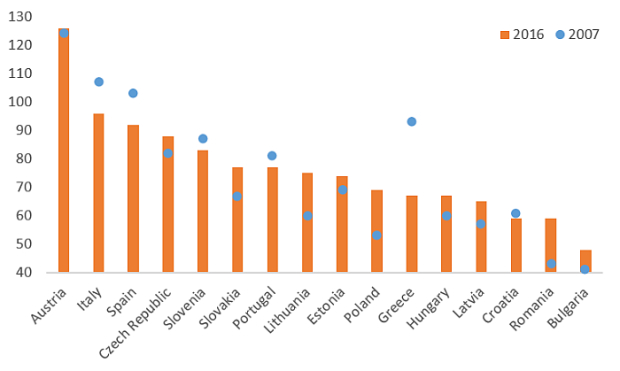

These rates of growth will ensure that convergence remains on track. While still far below wealthier EU member states such as Austria, EU-CEE countries with higher level of income such as the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Slovakia have already overtaken the poorer “old” member states, and are catching up with Italy and Spain.

Broader risks

Despite this relatively upbeat picture, we continue to see some risks to the regional economic outlook. Brexit will create problems for EU-CEE, not least as it is highly likely to shrink the EU budget. Net inflows from Brussels currently make up 2-5% of GDP per year for EU-CEE countries. Meanwhile, the economic risks of populism and politics remain significant. Upcoming elections in Austria and Italy could produce negative outcomes from the EU-CEE perspective, in relation to EU funds, free movement of labour, or the potential that negative political outcomes could affect the economies of these countries, both of which are important sources of investment and export demand for EU-CEE. Emmanuel Macron, the new French president, clearly has at least some EU-CEE countries in his sights. Meanwhile, recent news from Germany provides a remainder that structurally the euro zone has some way to go. EU-CEE countries, even those that are not members of the single currency, would suffer from any return of the euro zone crisis.

In addition to these potential threats from outside the region, there are also country-specific risks in EU-CEE. In Romania, loose fiscal policy has attracted international criticism and created concerns about medium-term macroeconomic stability. Meanwhile in Hungary and especially Poland, political risk remains elevated, and could have an impact on economic activity. However, the potential for serious measures by the European Commission against Poland, including cuts to EU fund inflows, would almost certainly only be felt in the next funding period post-2020.