The growing internationalisation of Austrian exports

23 November 2018

Trade, investment and migration links with CESEE are still extensive, but the real story of the last decade has been Austria’s increased integration with non-EU economies.

By Richard Grieveson and Mario Holzner

- A major new study by wiiw finds that Austria’s export structure has become more internationalised over the past decade, with firms increasingly able to take advantage of faster growth in non-EU markets.

- In gross terms, Austria has lost global export market share since 2004. However, in value-added terms, Austrian exporters increased their share between 2000 and 2014.

- The ability of Austrian exporters to tap faster-growing non-EU markets has been achieved primarily by improvements in price competitiveness. Higher demand in some key trading partners has also helped.

- Markets in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE) remains highly important for Austrian exporters. However, our study does not support the idea that Austria is “locked in” to the region.

- Austria’s main two export sectors are machinery and transport equipment. The former heads to a large extent out of the EU, while the latter is directed mostly towards Germany. Germany remains by far Austria’s most important trading partner.

- Austria’s high reliance on exports relative to many other Western European countries means that it is particularly important for policymakers to legislate in a way that improves the country’s competitiveness.

- Our study concludes that policymakers should aim for a productivity-oriented wage policy, an industrial policy that aims at technological upgrading and EU policies that speed up income convergence across the continent, and seek to further increase the country’s exposure to faster-growing markets outside of Europe.

In gross terms, Austria’s trade performance relative to global peers has worsened since the start of the 2000s. Austria’s share of global trade peaked in 2004, the year that ten new member states joined the EU, and has declined since. In gross terms, Austria has lost export share to Germany.

However, although Austria’s share of global trade in gross terms has declined since 2004, we found that Austria managed to increase its global export market share in terms of value added between 2000 and 2014. A big reason for this has been rising demand in some markets, which we found to have an important impact on Austria’s export performance.

In addition to increasing their exposure to faster-growing markets, Austria’s exporters have improved their price competitiveness. Among other factors, this is likely due to an expansion of regional production networks, which allowed for a reduction in export production costs.

Productivity developments has also been important. Austrian firms’ total factor productivity (TFP) on average is generally at average Western European levels, but higher than peers in the manufacture of beverages and in computers, electronics and optical products.

We find that EU regional policy support for Research, Technology and Development has generally a positive impact on productivity growth for less productive firms. National governments’ fiscal policy has also had a positive impact on the growth of firms’ TFP. An appreciation of the real effective exchange rate of a country also has a positive relation with its firms’ TFP growth. This mechanism appears to work as a sort of productivity whip pressuring firms to innovate and increase TFP.

Is Austrian industry “locked in” to CESEE?

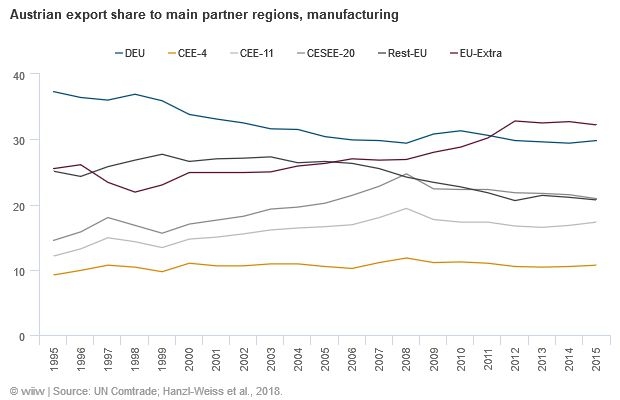

Trade between Austria and CESEE, and particular with near neighbours (including the Visegrád countries) has expanded rapidly since the mid-1990s. Austria’s trade share with these countries has increased, while it has decreased with Germany. However, the major shift happened before 2004. We do not find that the accession of some CESEE countries to the EU has harmed Austria’s role in German supply chains. Austria has remained a key supplier of transport equipment to Germany.

Overall, we did not find strong evidence for a “lock-in” effect of Austria with the CESEE region. Austria’s potential CESEE lock-in effects (which we define as higher trade flows than would be expected using a typical gravity model) have been stagnating since the outbreak of the global financial crisis. Austria’s excessive exports (those greater than would be predicted by a gravity model) have been directed more to Western Europe rather than to CESEE since 2012.

The most significant shift in Austrian trade over the past decade has been away from the old EU member states, and towards extra-EU countries, especially in machinery exports. This is likely to have been influenced by persistently weak post-crisis demand in many parts of Western Europe, and strong growth in other parts of the world. This development further reinforces the conclusion that Austria is “locked in” to CESEE markets. On the contrary, these results would suggest a growing internationalisation of the Austrian export structure.

Policy recommendations

Austria’s economy has a relatively high dependence on exports, more so even than Germany, and much more than other big Western European countries such as France, Italy and the UK. This means that it is especially important that policymakers in Austria continue to legislate in a way that is supportive of the country’s exporters.

Out study finds that policy recommendations that aim at further improving Austria’s competitiveness are needed in order to avoid potential negative lock-in effects in the future. It is possible to distinguish two major types of policy measures. One deals with the rules of the game, the other one with immediate causality. The former might be called neoclassical, and is mostly what one means by structural, while the other is Keynesian, and is interventionist. In the Austrian context the following policy mix of both types seems to be particularly relevant:

Wage policy: The question of wage policy should not be reduced to the issue of price competitiveness and export performance. Wages play a dual role as they are not only the most important cost competitiveness component for many firms but also represent the incomes of employees, so that wage growth is highly important for sustaining adequate domestic demand. Against this background, striking a balance between price competitiveness and demand-side considerations in the long-run could be achieved by following the so-called Benya formula, according to which wage policies should be a function of inflation and productivity. In particular, yearly wage growth should compensate both for the inflation rate and medium-term productivity growth. Moreover, given some of our results which might hint at the potential function of a real effective exchange rate appreciation as a productivity whip and in view of current macroeconomic imbalances (current account surpluses and unemployment), occasional overcompensation might have overall positive effects on foundational competitiveness, defined as GDP at PPP per working-age individual.

Industrial policy: As Austria's technological capabilities are highly important for the future of its growth model, targeted industrial policy could foster the technological position by pushing for investments in knowledge policies that support technological, organisational and institutional innovations. Policymakers could also work to ensure sufficient national supply of a highly-skilled labour force, which requires appropriate education policies. Domestic policies should also focus on improving the mobilisation of the working-age population by measures such as working-time reductions and active labour market policies. Given our research findings on the positive impact of national government expenditures on firms’ productivity growth, a larger public sector should be an aim in order to create both more supply as well as demand for innovative new products.

Policies at the EU level: Austrian policymakers should support European policy measures that prevent disruptions in trade with important trading partners. A sustainable strategy therefore requires policies that allow for a continuation of the catching-up process in Central, East and Southeast Europe and a European policy agenda that supports convergence within the euro area. This point underscores the importance of well-coordinated monetary and fiscal policies that allow for proper management of aggregate demand at the European level. Moreover, given our findings on EU regional policy, i.e. that support for Research, Technology and Development that has a positive impact on productivity growth for less productive firms, structural policy tools could be topped up in order to move economic convergence in Europe forward.

Increasing exposure to faster-growing economies outside Europe: Policymakers should also think about how to increase exports to regions that could be expected to feature higher growth rates and increasing demand for capital goods in the future. For example, such an orientation of Austrian capital goods exports could be developed in the context of a strategy for future economic relations with India and Africa. Successful internationalisation activities such as the global network of offices of the Advantage Austria initiative of the Austrian Economic Chamber should be boosted in scope and targeted towards promising markets.

photo: iStock.com/pxel66