Trump’s ‘reciprocal’ tariffs: A farcical repetition of the tragic trade policies of the 1930s

03 April 2025

Trump’s latest global tariffs, announced on a self-proclaimed ‘Liberation Day’, will likely cause sharp short-term trade declines – and a significant surge in inflation for the US

image credit: unsplash.com/Yoav Aziz

On 2 April 2025 – his self-proclaimed ‘Liberation Day’ – President Donald Trump once again announced new tariffs. This time, all US trade partners will face a minimum ‘discounted reciprocal tariff’ of 10%. For countries with trade surpluses deemed guilty of ‘currency manipulation and trade barriers’, tariffs could rise to nearly 50%. Southeast Asian export-driven economies will particularly be affected. Major trading partners – such as China (34%), the EU (20%) and Japan (24%) – will face intermediate rates, although they are extremely high by historical standards. Regarding China, the official White House communication is unclear, but Trump's press secretary indicated that these new tariffs are in addition to previously imposed and announced measures. The UK and several other countries will be subject to the ‘baseline’ 10% tariff. For Canada and Mexico, the situation is more complex, as previous fentanyl- and migration-related tariffs will remain in effect. Additionally, tariffs on goods already targeted (e.g. steel, aluminium and cars) will stay in place. Exemptions include inter alia copper, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors and lumber as well as energy imports and certain minerals that are not available in the US.

As mentioned in an earlier post on Trump tariffs against Canada and Mexico, already during his first administration, Donald Trump introduced a series of protectionist trade measures targeting multiple countries, most notably China. In January 2018, he imposed 30-50% tariffs on solar panels and washing machines. This was followed in March by 25% tariffs on steel and 10% on aluminium, initially affecting most countries and covering more than 4% of US imports. By June, these tariffs had been extended to the EU, Canada and Mexico. Separately, a series of escalating tariffs on Chinese imports triggered retaliatory measures by China, specifically in the areas of critical raw materials that are necessary inputs in chip and battery production.

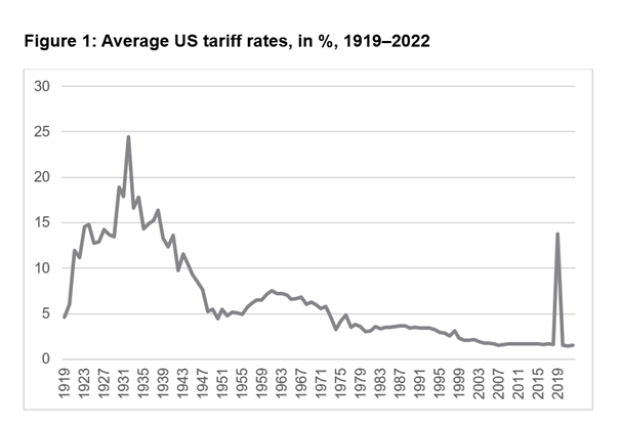

President Trump has effectively ended decades of US advocacy for free trade. Although some trade barriers were already introduced during the Obama administration, the current radical tariff hikes evoke comparisons to the last US-led global trade war, initiated by a series of three Republican presidents who governed from 1921 to 1933: Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. The Emergency Tariff of 1921 was introduced in response to plummeting agricultural prices after the First World War. This was followed by a significant escalation in the form of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which raised US tariff rates to an average level of 25% (Figure 1). The US trade restrictions provoked a global trade war, which, combined with the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, arguably contributed to the rise of fascism in Europe and Asia.

Figure 1 / Average US tariff rates, in %, 1919-2022

Note: From 1919 until 1994, bilateral customs duties-to-imports ratios; from 1995 onwards, weighted average tariff rates.

Sources: CEPII TRADHIST v.4, WITS, own calculations.

How will the ‘reciprocal’ tariffs of ‘Liberation Day’ impact the global economy? While general equilibrium trade models typically predict modest long-term effects as economies adjust to the new normal, partial equilibrium models can better capture the immediate and disruptive short-term impacts of tariff hikes, as they largely disregard second-round effects. To assess these short-term consequences, we apply the partial equilibrium global simulation model (GSIM) to the current situation for the US, Canada, Mexico, China, Japan, the UK, the EU and the aggregated rest of the world.

In our model, goods trade flows are based on UN COMTRADE 2023 import and export data in USD. Domestic trade is approximated using 2023 GDP data from the WDI database. Initial tariff rates are taken from the 2022 ad valorem simple average rates in the WITS database. Following the outlined scenario, we assume US tariffs will increase to 34% on China (excluding previously announced tariffs), 20% on the EU, 24% on Japan, and 10% on the UK. As the situation with Canada and Mexico is less clear, for the sake of simplicity, we assume 10% for both and 20% for the rest of the world. To ensure a conservative estimation of trade effects, we apply a composite demand elasticity of -0.5, an industry supply elasticity of 0.6, and an elasticity of substitution of 2.0 along half of their lower bound values in earlier research.

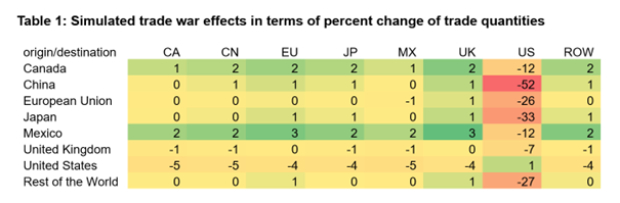

The projected trade impacts on most trading partners of the US are substantial. According to the model, Chinese exports to the US could decline by approximately half, while EU exports to the US may drop by around a quarter. Japanese exports to the US are also expected to decrease by a third (Table 1). The model predicts a significantly smaller decline in US imports from the UK, Canada and Mexico. Meanwhile, the US is expected to experience a decline in exports to all other regions, as domestic price levels are likely to increase due to the trade war. It is important to emphasise that these trade shifts reflect short-term effects, which are likely to be much stronger than longer-term adjustments. Factors such as exchange rate fluctuations and supply chain realignments (which are not considered in this analysis) could mitigate some of these impacts over time. A sharp appreciation of the US dollar could even have a substantial short-term impact.

Table 1 / Simulated trade war effects in terms of percent change of trade quantities

Source: Own calculations using the partial equilibrium GSIM model.

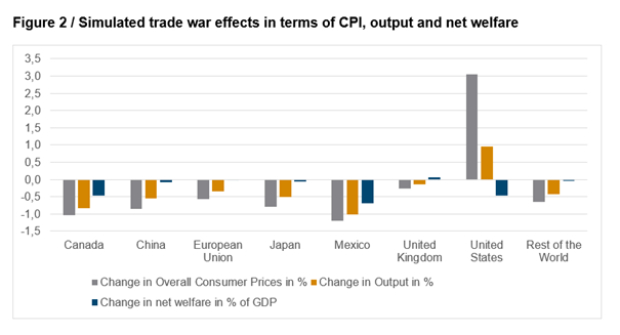

The US is expected to experience an additional inflation surge of three percentage points (Figure 2). At the same time, consumer prices in all other regions are projected to decline by between 0.5% and 1%, as some goods originally destined for export will be redirected to local markets. Conversely, while US output is expected to grow by about one percentage point, other regions are likely to face output declines of around 0.5%. Overall, most parties involved in the trade war are projected to experience net welfare losses, measured as the combined effect of producer surplus, consumer surplus and tariff revenue. Interestingly, due to the high increase in prices, the US would be one of the most (negatively) affected economies, with a projected welfare loss of about 0.5% of GDP. While US manufacturing firms and workers may benefit, overall consumer losses are likely to outweigh these gains.

Figure 2: Simulated trade war effects in terms of CPI, output and net welfare

Source: Own calculations using the partial equilibrium GSIM model.

The analysis suggests that while a trade war would generally harm all parties, the US manufacturing sector may see temporary gains. In the long run, Trump’s across-the-board ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs could reshape US production and trade patterns, causing significant disruptions in export-driven economies like China and the EU – although the full extent remains uncertain.