wiiw Opinion Corner: Likely reasons and consequences of Hassan Rouhani’s victory in the Iranian presidential elections

26 June 2017

Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, aiming for moderate reforms and better relations to the international community, won his second term in office, far ahead of his hardliner rival Ebrahim Raisi.

By Mahdi Ghodsi

Iranians hail moderate reforms

On 19 May 2017, Iranians cast their votes in the country’s twelfth presidential election. The Islamic Republic of Iran has some features of democracy, which makes it very different from the monarchies in some neighbouring countries. Its republican system was designed and advocated in 1979 by the founder of the revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. This time, the incumbent president Hassan Rouhani, aiming for moderate reforms and better relations with the international community, won his second term in office with 19% of the votes, far ahead of his hardliner rival Ebrahim Raisi.

The hardliner candidate

Mr Raisi has recently been appointed by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei(1), to the largest tax-free charity of the Muslim world, as the custodian of the Imam Reza Holy Shrine (Astan Quds Razavi) in Mashhad. However, among Iranians, Mr Raisi is remembered first of all for his long reputation in the judiciary (the hardliner institution of Iran suppressing freedom), and as one of the four judges in the late 1980s ordering numerous executions and imprisonment. He is still speculated to be a candidate for the next ‘supreme leadership’ (the chances of which would have increased if he had become president). He promised nothing less than six million new jobs, and increasing budget transfers to the three bottom deciles of income distribution during his presidency. This populist rhetoric was very similar to that of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and aimed at attracting the poor population in the rural areas as well as Islamic hardliners, while naming no budgetary resource for such promises. Moreover, as addressed by Mr Rouhani in one of the televised debates, Mr Raisi’s team of economic advisors are mostly identical with those of Mr Ahmadinejad, who had mismanaged the economy.

Reasons behind Mr Rouhani’s victory

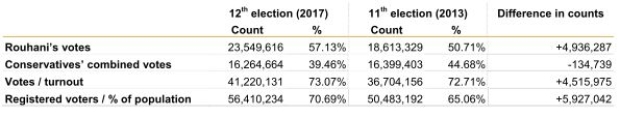

Mr Rouhani’s victory is mostly indebted to the young population of Iran that were not yet eligible to vote in the previous presidential election (Table 1). Iran’s demography has resulted in around six million new eligible voters above the age of 18 in the recent elections. While four and a half million votes added to the new casts, the turnout did not change from the previous presidential election. The results might suggest that the young generation with better connections to the outside world has chosen a progressive open society supporting the social reforms advanced by the reformists in Mr Rouhani’s camp. The combined number of votes to four conservative candidates in the previous presidential election was slightly larger than that to the two conservative candidates in this election. This trend may indicate a further shift in society towards moderate reforms also in the future.

Table 1: Vote structure of the presidential election – moderates vs. conservatives

Mr Rouhani’s success was also in large part due to bringing back the centralised and oil-dependent economy to discipline, choosing a cabinet based on meritocracy, and making a historical deal with the West removing the sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear activities(2). Despite high economic growth (6% last year), largely thanks to increased oil revenues (in spite of low prices), these achievements have not substantially affected Iranians’ daily lives. Unemployment remains high, with a rate around 15-17% – a legacy of the government of Mr Ahmadinejad, who ignored the five-year development plans that were designed to respond to the enormous population growth during the 1980s.

Obstacles ahead

There are certain issues hindering Iran from becoming better involved in the international economy, enjoying advantages from foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade. These issues are mostly linked to the remaining non-nuclear sanctions from the United States. Mr Rouhani has promised to resolve these issues in his second term if he is allowed, in particular if mandated, and guided by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Accusing Iran as the state sponsor of terrorism, testing ballistic missiles, and increased tensions with the US allies in the region are the major reasons for the ongoing US sanctions. Unless Rouhani manages to strike a new deal with the US on these issues, Iran might be facing even more severe consequences. The timing of the first foreign visit of Donald Trump to the US allies in the region, which coincided with the Iran presidential election, also sends such a signal. This visit was set to appease the US allies in the region after Obama’s administration had left them unhappy by reaching a deal with Iran. The deal and the unsatisfactory relations with Obama triggered the Arab allies of the US to rush into a war in Yemen, raising the tensions with Iran which supports the Shiite opposition in the proxy war.

Also, the Iranian President – by the constitution the second top authority in the Islamic Republic – is usually less successful in his second term. The conservative institutional power might potentially sabotage the moderate government fulfilling its promises, which in turn may repulse disappointed voters from the next round of presidential election(3). Given that the foreign policy is primarily directed by the first top authority, the Supreme Leader, it is most likely that Mr Rouhani will continue strengthening ties with the European Union rather than solving a four-decade animosity with the United States.

Support from the EU

The EU’s congratulations to Rouhani’s election victory, seen as a symbolic act appreciating the ongoing path of Mr Rouhani towards greater openness to the world, spell hope for the educated young population of Iran as concerns further economic development and political reforms in Iran in the future. Mr Rouhani’s success will thus be conditional on attracting more FDI from the EU that could deliver a better environment for creating job opportunities for the young. Iran-EU trade relations have substantially improved in 2016 after the nuclear deal was signed. Besides, it is worth mentioning that Iran’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) – which could provide Iran with better economic relations with the world – is supported by the EU while opposed by the United States. Not having a very strong voice contrasting the US, the EU, however, has remaining demands, which are being addressed on several occasions such as a meeting with Javad Zarif, the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs, in the European Parliament for questions and answers. These remaining requests may potentially result in moderate domestic social reforms in Iran concerning human rights and freedom of speech. Other demands are related to regional issues resolving the Syrian crisis, and the fight against terrorism.

Footnotes:

(1) Ayatollah Khamenei is the second Supreme Leader of Iran after the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic. The Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution is the head of state and the highest ranked authority in the Republic. He appoints the heads of main state organisations, the armed forces, the judicial system, the Expediency Discernment Council of the System, state television and broadcasting, etc. Additionally, he appoints six clerics out of twelve members of the Guardian Council directly while the six others are nominated by the head of the judicial system and elected by the parliament. The Guardian Council is in charge of the vetting process of all nationwide elections including the presidency, and the Assembly of Experts, who is mainly in charge of appointing and monitoring the Supreme Leadership.

(2) See: ‘What are the consequences of the Iranian sanctions relief?’ by Mahdi Ghodsi, in: wiiw Monthly Report No. 2/2016

(3) This was observed after the second term of the reformist president Mohammad Khatami (3 August 2001 – 3 August 2005), leading to a much lower presidential election turnout in 2005 (62.66% in 2005 compared to 77.1% in 2001) and resulting in the hardliner candidate Mr Ahmadinejad’s victory.

Photo credit: By Mojtaba Salimi (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons