Are we heading for a bigger emerging markets crisis?

22 August 2018

The Turkey panic may just be the first indication of a broader sell-off as US rates continue to rise, and many in CESEE could be affected.

- US monetary tightening has sucked dollars backed to the US and seen many emerging market currencies weaken quite strongly in recent months.

- Turkey has suffered particularly badly, reflecting additional domestic factors, but many others in CESEE have also been affected.

- Although Turkey clearly stands out, we view several other countries in our region as vulnerable as US rates continue to rise. Many have significantly increased their external debt loads over the past decade, while some continue to run large current account deficits. A few countries in the region could also be vulnerable from a sovereign debt perspective.

- However, we expect US tightening to proceed only slowly from here, while the pace of rate hikes by the ECB is likely to be even more sluggish. This will provide a valuable source of stability for the more vulnerable countries in CESEE over the coming years.

Many emerging market assets have come under strong selling pressure in recent weeks. While Turkey has been the most affected (see our coverage here), it has been far from the only case. Markets such as South Africa and Argentina have also suffered, while countries in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE)—notably Russia—have experienced sell-offs.

There are clearly some idiosyncratic factors behind the market panic. In the case of Turkey, domestic policy failures have played a major role. For both Turkey and Russia, much of the market pressure have resulted from the imposition of US sanctions. Yet for emerging markets as a whole, including in CESEE, the stronger dollar on the back of continued US monetary tightening has been a key driver.

The US Federal Reserve has pursued ultra-loose monetary policy for a decade. While this saved the global economy from a much more savage downturn in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, it has also contributed to bubble-like conditions in many riskier asset classes. Starved of yield in safer markets, a lot of money (including from traditionally conservative institutional investors) has gone into riskier bets, including emerging market stocks, bonds and currencies.

US tightening drives dollars back home

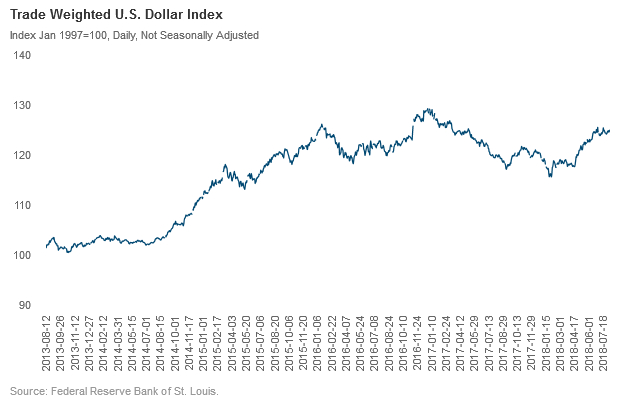

It has always been clear that this could not last forever, and that at some point US rates would start to rise, sucking dollars back to the US and away from emerging markets. Ever since the 'taper tantrum' of 2013, the risk of a disorderly stampede for the exit have been evident. Several episodes of volatility in emerging markets assets linked to US monetary tightening have further reinforced this point.

Since April, a new bout of such volatility has been seen, and in some emerging markets (especially Turkey and Argentina) the sell-off this time has been particularly savage. Although the pace of US tightening has not visibly quickened, the dollar has risen notably against the euro. In April, one euro bought US$ 1.24. It now buys less than US$ 1.14.

This will not inevitably end in a crisis. Yet the risks are clearly there. The “1994 scenario”—when a rise in US rates after a long period of loose monetary policy was very disruptive in global financial markets—has been widely discussed recently. Collapses in some particularly risky markets have already occurred: the bitcoin bubble appears to have decisively burst, for example. Yet there are concerns about what will happen in other markets with far greater systemic importance. Italian bonds and Chinese debt—both of which have worried investors at times over the past year—are two assets classes where a downturn would have much more dramatic implications.

Where are the areas of vulnerability in CESEE?

CESEE will certainly not be immune to these developments. We covered the potential areas of vulnerability in our Spring Forecast report. As we highlighted then and subsequently (see here and here), Turkey clearly stands out as the country most at risk in the region. The country’s gaping current account deficit, large short-term FX-denominated debt rollover needs, rampant private credit growth and high inflation create a particularly volatile mix. As we wrote back in March, “Turkey is the country in CESEE where we see the biggest risks from a faster-than-expected hike in US rates or a more general rise in risk aversion among investors”. Among G20 countries, only China has seen a faster rise in private sector debt/GDP and the debt service ratios over the past ten years. Unfortunately, our expectations have proven to be correct. Nevertheless, many other countries could suffer in a sell-off.

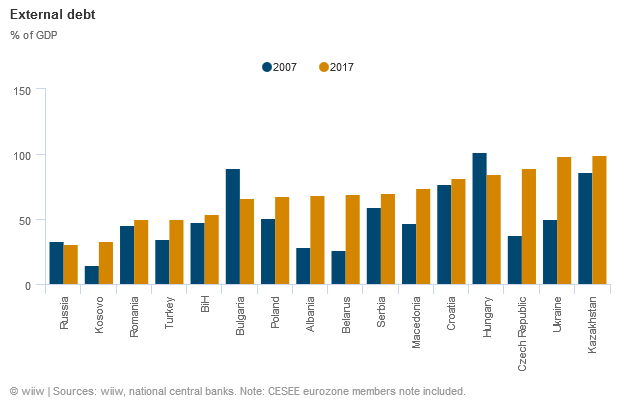

One key indicator of vulnerability that we assessed in our Spring Forecast report was external debt. Much of CESEE has participated in the ramping up of external corporate credit since 2008, as firms have taken advantage of ultra-low borrowing costs. As we noted in March, gross external debt/GDP ratios have risen across most of CESEE since 2009, with the biggest increases recorded in the Czech Republic, Ukraine, Belarus, Albania and Macedonia (all 25pp of GDP or more as of end-2017). In terms of the overall levels, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, the Czech Republic, Croatia and Hungary stand out. Short-term external debt is notably high in the Czech Republic, Kosovo, Turkey and Belarus, although in the past decade most countries have reduced their reliance on short-term debt (with Turkey being a key exception). Corporate eternal borrowing was particularly high in Kazakhstan (88% of GDP at end-2017), but was also elevated in Croatia, Macedonia, Bulgaria and Ukraine.

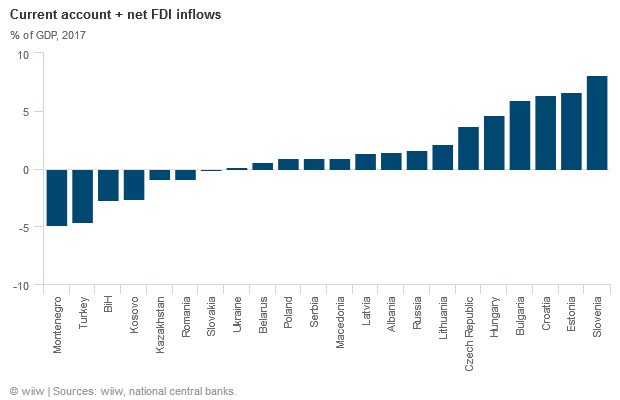

A second key metric to access external vulnerability is the current account deficit adjusted for net foreign direct investment inflows (FDI; which tend to be a more stable form of financing). There we found that much of CESEE had undergone a positive adjustment since the global financial crisis (in part because the persistent weakness of domestic demand had held down imports). However, we found that several countries were still running FDI-adjusted current account deficits (see chart below). Although we noted that some—particularly Kosovo and Bosnia—were able to rely on a large share of concessional financing, this was clearly not the case for Turkey in particular, which relied heavily on “hot money” to plug the gap.

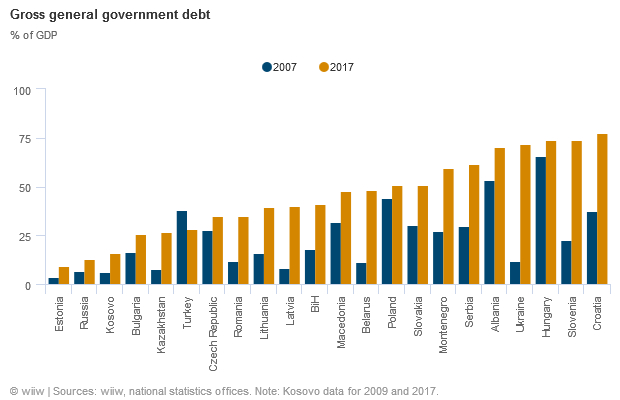

The third indicator we looked at was sovereign debt. We noted at the time of our Spring Forecast report that the three major ratings agencies had a particularly positive outlook on the region’s sovereign debt, with only Turkey on negative outlook at the time (last week, Turkey’s sovereign credit rating was downgraded by both Moody’s and S&P). However, we also highlighted that public debt/GDP ratios had risen in almost every country in the region over the past decade, and that seven stood above 60% (Montenegro, Albania, Serbia, Hungary, Slovenia, Ukraine, and Croatia). Although ultra-low global rates make this less of an issue than it otherwise would be (and are the reason for much of this debt build in the first place), this will not last indefinitely.

One interesting point to note is that, across the various indicators of external vulnerability that we assessed, Russia is absent. Russia has been buffeted by international sanctions in recent years, and these measures look set to only intensify in the near term. However, it is as well placed to deal with this as pretty much any country in CESEE, thanks to its very low debt levels and current account surplus, plus large foreign currency earnings from the hydrocarbon sector. This will continue to make Russia much less vulnerable to international developments—both US monetary tightening and sanctions—than regional peers such as Turkey.

Reasons not to worry?

Investors should not be complacent about the risks in CESEE, as market activity of recent weeks has shown. However, we believe that some of the worst fears are overblown. In particular, we still see a fairly strong likelihood that global rates will continue to only rise slowly. US inflation remains remarkably low considering the economic backdrop, which suggests that the Phillips Curve is not as useful as it once was. This is even more the case in the eurozone, where rises in oil prices are masking an otherwise remarkable lack of price growth in many countries (recent spikes in wage growth in Germany notwithstanding). As a result, the ECB will only move very cautiously in normalising monetary policy. Given that the ECB rate is more important than that of the Fed for most of CESEE, this will provide valuable shelter to much of the region as global stimulus is unwound.