Disappointing EU summit: Will the ‘recovery fund’ be large enough?

27 April 2020

The meeting of the heads of state and government last week still lacked viable solutions for European burden sharing of corona crisis costs through a ‘recovery fund’.

by Philipp Heimberger

photo: istock.com/Alexandros Michalidis

- As northern euro area countries still insist on loans that are to be paid back by the countries hit hardest by the pandemic, the EU’s leaders fail to agree even on basic principles.

- The northern euro area countries, however, should avoid making the mistake of insisting that the recovery fund must be financed by loans to be paid back by hard-hit countries. Grants are required to avoid even bigger public debt problems down the road.

- The European Commission will now make a proposal concerning size and financing for the “recovery fund”.

- The lower limit in terms of size should be 1,000 billion euros (about 8% of euro area GDP).

- The recovery fund must not be based on simply renamed existing or small pots of additional money that are “leveraged” to much larger sums.

As many observers feared, EU leaders last Thursday failed to make any significant progress in the struggle for a common European strategy to combat the Corona crisis by sharing the crisis costs; they were not even able to agree on a joint final declaration. The political rifts between Germany and other northern euro area countries (the Netherlands, Austria, Finland) and the southern euro area countries around Italy and Spain remain deep, despite all the positive political statements of unity after the summit.

The summit only decided on the 540 billion euros package previously agreed by the finance ministers. However, even after weeks of previous negotiations, it was not possible to agree on a clear political roadmap, let alone a concrete solution for the scope and financing of the envisaged "recovery fund". And as I argued elsewhere, these measures – ESM credit line, "EU short-time work scheme" (SURE) and loan guarantees by the European Investment Bank – are at best a first step and will not be able to stop the further drifting apart of euro area countries.

Even the principles of burden sharing are controversial

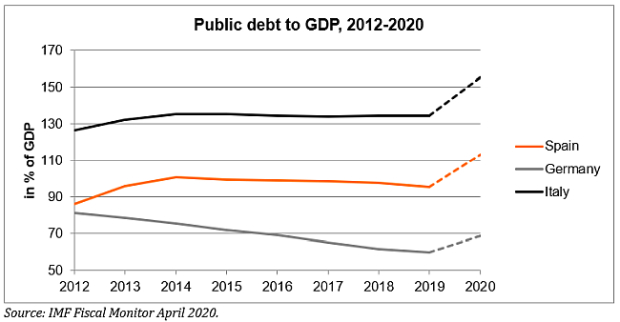

Unfortunately, however, the euro area needs such a concrete solution in order not to enter into another existential crisis. Some countries, above all Italy, are already going into the corona crisis with such a high level of public debt that they cannot simply take out more loans on a larger scale – as Germany and Austria are able to do –, as this would push up public debt even further. This is already evident from the fact that the fiscal policy response to the crisis in Italy and some other southern euro area countries has so far been much weaker than in Germany and Austria. In order to prevent that a continued asymmetric fiscal policy at the national level will further increase macroeconomic divergence within the Euro area, a strong European response is needed – which, according to the assurances of European leaders, should take the form of the "recovery fund".

But for weeks now, both the EU finance ministers and the heads of state and government have been busy shifting responsibility: At first, the heads of state and government of the Eurogroup pushed the "recovery" ball towards the Eurogroup: the finance ministers, however, were also unable to agree on the burden sharing of the costs of the crisis, and so the ball landed back at the European Council. Last Thursday, the European Council gave the ball to the European Commission.

The background is the dispute over central principles and guidance over what the recovery fund should look like. Northern European countries such as the Netherlands insist that loans must be repaid in full and categorically refuse grants. German Chancellor Angela Merkel also remains opposed to grants. However, sticking to loans that have to be repaid would once again drastically increase the level of debt in Italy and other countries particularly affected by corona – and this would lead to rippling effects in northern euro area countries down the road by further destabilizing the euro area.

The inability of the political leaders of the EU’s member states to agree on even the most central principles leaves the impression that they are still not willing to accept the seriousness of the situation and that the states in the south of the euro area, which are particularly affected by the pandemic, mostly have to deal with the crisis on their own.

Hope European Commission?

At the EU video summit on Thursday last week, the EU member states handed over responsibility once again: this time to the European Commission, which is to submit a proposal for the establishment of the "recovery fund". The Commission has already announced that the details of the fund and its financing will be negotiated under the umbrella of the EU's long-term budget. However, the experience with the extremely controversial EU budget negotiations from the pre-Corona era gives little reason to hope for improvement: on the contrary, the insistence of some EU member states – above all Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden – on hard limits for their countries' future EU contributions gives rise to fear that the "recovery fund" will once again be squeezed.

At the same time, it has been leaked that the EU Commission – as has already been the case, for example, with regard to the financing of the "Green Deal" and the Juncker Fund – plans to generate "leverage" from a relatively small pot of EU money through private sector involvement. This might serve to artificially inflate the sums involved in communicating with the public ("trillions instead of billions", as Commission President von der Leyen puts it). However, given the expected weak private sector investment activity following the Corona lockdown, this would not provide sufficient fiscal stimulus to open up positive recovery prospects for the southern euro countries. In any case, the integration of the "recovery fund" into the EU budget negotiations has not yet resolved any controversial financing issues, but the approach has so far put off concrete decisions on burden sharing.

If European policy continues in this vein, a large part of the economic policy burden, even in the "recovery phase" after the Corona lock down, will be on the European Central Bank, which is already holding the euro area together through major monetary policy interventions on government bond markets, while European fiscal policy-makers are failing to step up their game. This constellation has already had a politically destabilizing effect during the euro crisis and should not be perpetuated if the survival of the common economic and monetary area is the goal of decision-makers.

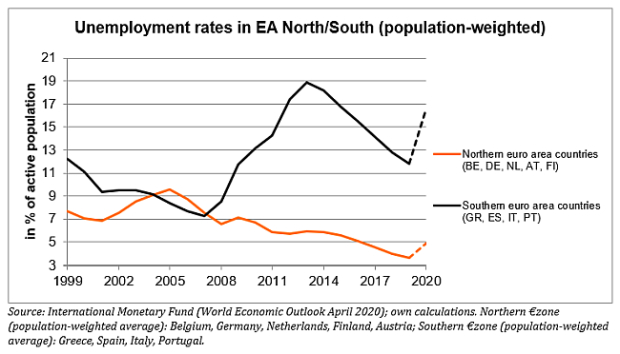

So while the Northern euro area countries continue to play for time, the hats in the Southern euro area are already on fire: the labour market situation in the South is already deteriorating drastically, and according to the latest IMF forecasts unemployment will rise strongly over the course of this year - much more so than in Germany and the other northern euro area countries, which can also do more to cushion the crisis with active fiscal policy. And on the financial markets, interest rates on Italian government bonds in particular have recently risen again – despite the extensive interventions by the ECB – because financial investors fear (even) greater problems for the debt sustainability of individual countries in the foreseeable future due to the disagreement among European political decision-makers.

Will the ‘recovery fund’ be large enough?

Nevertheless, the solution for European burden sharing does not necessarily have to be called "corona bonds". Spain, for example, has made a proposal for a fund of 1,500 billion euros, which would also not require joint debt liability for individual EU member states. The Spanish proposal would provide grants – not loans! – to the member states that would correspond to the damage caused by the pandemic. The programme would be pre-financed, would start on January 1st next year and would be paid out over two to three years. To make this possible, the EU would finance it through issuing perpetual bonds, backed by guarantees of the EU member states.

Money from the recovery fund could be used, for example, to finance health costs, expenditures on short-time working schemes to keep people in their jobs and, of course, the necessary fiscal stimulus programmes that will be required once lockdown measures can be lifted. For the recovery fund to have a noticeable effect on the countries particularly hard hit by the pandemic, it would need to be of a significant size.

The results of the recent EU summit of heads of state and government were particularly disappointing because central principles of common European burden sharing are still not beyond doubt. The northern euro area countries – led by Germany – should now avoid making the mistake of insisting on a large loan component of the recovery fund; grants are required to avoid even bigger public debt problems down the road. The lower limit should be 1,000 billion euros for the recovery fund.

To achieve a sizeable “recovery fund” (with very long maturities), the EU can issue debt, based on the capital base provided by the member states that provides the guarantee for these joint borrowings – this would, for example, be the approach in the Spanish proposal mentioned above. Joint debt liability would remain with the EU. The other option would be to raise the funds by agreeing on a strong (one-off) increase in the northern member countries’ contributions to the EU budget – but this seems very unlikely due to resistance from countries such as the Netherlands.

In any case, if the “recovery fund” is to have the necessary firepower to combat the crisis, it must not be based on simply renamed existing or small pots of additional money that are "leveraged" to much larger sums and these then communicated to the public. This was the case with the so-called Juncker Fund that was often questioned regarding how much additional investment it generated rather than just relabeling investment projects that were forthcoming in any case."

Germany and other northern euro area countries, heavily dependent on export-led growth and European regulation standards, have benefited strongly from the common European currency area over the past two decades. Northern euro area countries would therefore not simply act in solidarity if they were to abandon their hesitant stance on grants and financing issues when it comes to European burden-sharing, but would also do justice to their long-term self-interest in a well-functioning Economic and Monetary Union.