Improving Croatian employment opportunities is in everyone’s interest

24 April 2018

High emigration rates are a threat to the sustainability of Croatia’s social system. Austria and other wealthy EU member states can and should help to encourage workers to stay.

by Mario Holzner and Hermine Vidovic

Photo: Rijeka fish market, Bor Dizdar, CC-BY-NC 2.0

- By 30 June 2020 at the latest, Croatian residents will have full access to the EU labour market.

- Currently, transitional restrictions on access of workers from Croatia still apply in Austria, the Netherlands, Slovenia and the UK.

- Croatia has recovered only slowly from the crisis and continues to suffer from high unemployment and emigration. If this is not addressed, it will threaten the sustainability of Croatia’s welfare state.

- Reducing incentives to emigrate would be in the interests of both Croatia and the major destination countries for Croatian workers, including Austria. Therefore the Austrian government, and its EU allies, should help to improve the quantity and quality of employment opportunities in Croatia.

- wiiw’s major recent study (in German) on the issue suggests the following six areas of focus to encourage workers to stay in Croatia: improving export capacity and external competitiveness, increasing investment, promoting tourism, aiding Bosnia, strengthening agriculture, and broadening the industrial base.

Despite a recent moderate upswing, the Croatian economy continues to face major structural challenges, and as a result has continued to see an outflow of many of its younger and better-qualified workers. If this outflow continues, the economy and the sustainability of the welfare state will be in serious trouble in the long run. Urgent action is required, and wealthier EU member states which tend to be the main hosts for Croatian migrant workers—including Austria—can and should play an important role in finding solutions.

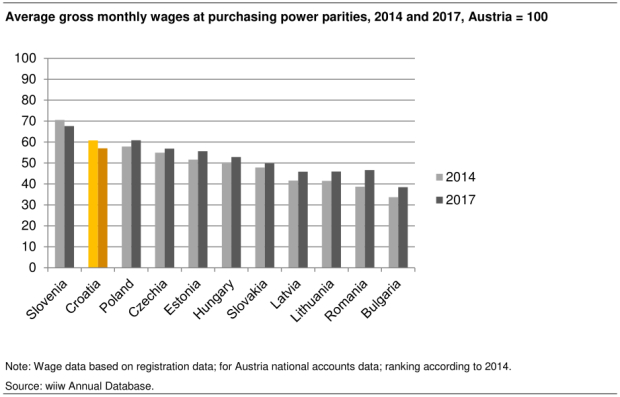

Similar to the situation in other EU members countries in Central and Eastern Europe, the Croatian wage level (adjusted for purchasing power) is still less than 60% of e.g. the Austrian one. However, while in most other countries of the region wages have caught up significantly in recent years, the opposite has been the case for Croatia (see chart below).

The major reason for this was the overvalued exchange rate leading to high foreign trade deficits in the period prior to the global financial crisis. Subsequently, those deficits could no longer be financed, and only a painful process of real devaluation (at a nominally fixed exchange rate) over a six-year period of recession restored the external equilibrium.

The price to be paid for that process was a drop in real wages and mass unemployment. More recently, however, unemployment has started to fall, particularly as a result of the outflow of labour to other EU countries. This has become increasingly possible since Croatia’s accession to the EU in 2013 and has further strengthened since Germany – the main destination country of Croatian migrants - lifted labour market restrictions for Croatian citizens on 1 July 2015. In some countries – among them Austria (and probably the Netherlands and Slovenia) – labour market restrictions will likely remain in place up until 2020.

Urgent action required to ensure long-term sustainability of welfare state

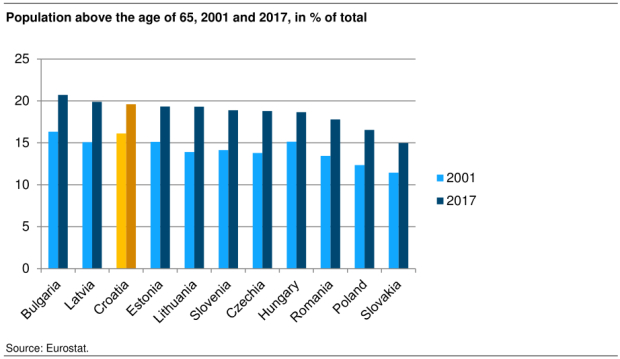

Croatia is a country with a strongly ageing population (every fifth Croat is above 65 years of age), not least because of continuous emigration. To ensure the long-term stability of the social system, therefore, a trend reversal is essential. Domestic policy options available to the Croatian government are limited. In order to create the necessary economic basis, therefore, Croatia needs external support.

wiiw recently undertook a major study looking at how to improve the situation in Croatia. The conclusions of the study highlight a strong role for external partners, including Austria, in promoting development in Croatia, bilaterally as well as jointly with the EU. As one of the countries still applying transitional restrictions on Croatian workers, Austria has a particular interest in supporting Croatia, and should use the opportunity of its EU Council presidency in the second half of 2018 to further this agenda. Austria and other EU governments could provide the following specific assistance to Croatia.

Six areas of focus

1. Increase export capacity

The exchange rate of the Croatian currency, the kuna, is almost completely pegged to the euro. Extreme euroisation and the high foreign debt thus do not allow for devaluations in order to stimulate export activity and increasingly attract export-oriented foreign direct investment to the country. Alternatives to a nominal devaluation are (budget-neutral) fiscal devaluations as well as an income policy aimed at maintaining foreign trade equilibrium and guided, in the long term, by the development of productivity and inflation. As the Croatian wage bargaining system is decentralised and lacks coordination, Austrian social partners (i.e. employees’ and employers’ organisations) could provide institutional assistance in this respect and propagate the system of social partnership and its macroeconomic advantages.

2. Increase investment

Owing to the crisis and because of the rigid fiscal regulations of the EU, the Croatian government, on its own, is not in a position to make significant investments in infrastructure or to provide generous investment incentives for foreign investors. Greater fiscal leeway, particularly in the case of investments in the future, could be facilitated by a change in EU regulations (for instance, the introduction of the ‘golden investment rule’). In addition, increased support through EU subsidies is needed. The economy’s absorption capacity of EU subsidies has to be increased (this will require better institutional capacity, including at the local level). Furthermore, Croatia must not become a victim of Brexit in the forthcoming renegotiations of the EU budget. In both respects EU governments could support Croatia: by bilateral institutional assistance in increasing absorption capacity and in project development, and by political support particularly for the three poorest EU Member States (Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia) in the EU budget negotiations.

3. Promote tourism

Croatia’s south along the Adriatic coast, focused on summer tourism, needs investment in higher-quality services in order to significantly extend the tourist season and to make better use of existing capacities. EU member states could encourage the establishment of a new joint research centre of the European Commission in southern Croatia. This could lead to year-round conference tourism. Other important measures at the EU level, also for tourism, in which the Austrian and other EU member states’ governments could support Croatia, would be rapid accession to the Schengen area and the eurozone. Among the euro convergence criteria (also known as the Maastricht criteria) the government debt-to-GDP ratio is the main stumbling block for accession in Croatia’s case. In 2017 it was at 78% of GDP. According to the Maastricht critera, it must not exceed 60% or it should have sufficiently fallen and must be approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace. Last year it fell by almost 5 percentage points, which might be seen as a satisfactory pace even if the strict criteria is not yet fulfilled. The indicator peaked in 2014 at close to 86%.

4. Aid Bosnia

Half of the Croatian border – especially in the structurally weak south and east of the country – is shared with Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnia is one of the poorest countries in Europe and is institutionally unstable. In addition, Bosnian Croats with dual citizenship are also entering the Croatian labour market. Anything that could improve the situation in Bosnia and beyond throughout the Western Balkans would also be of great benefit to Croatia. EU members’ governments could lobby for a change of the constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina to make the country more functional. Moreover, member states could increasingly advocate the accession interests of all Western Balkan countries and support them even more strongly within the framework of the so-called Berlin Process and EU pre‑accession aid. Interim solutions, such as partial accessions of these countries in selected areas of the EU acquis, should also be considered.

5. Strengthen agriculture

An improvement of the economic situation in Bosnia could also benefit eastern Croatia, which is largely agricultural and has only a few larger industrial enterprises. Increasing productivity in agriculture and forestry and at the same time building up downstream industrial production would be of great help to the poorest region of Croatia. Austria in particular has a long experience in the promotion of rural areas and in the field of cooperative organisation of the agricultural sector. This could lead to increased cooperation and knowledge transfer.

6. Broaden the industrial base

Northern Croatia has a stronger industrial base as compared to other parts of the country. However, this is largely obsolete and located in the low- to medium-technology sector. This Croatian core region, which accommodates almost half of the total population, requires foreign direct investment in the manufacturing industry and the associated integration into technologically advanced international value chains. Some innovative companies in the field of e‑mobility, which already exist in and around the Croatian capital of Zagreb, could be a possible starting point. Austria’s Styrian automobile cluster is located in close proximity to northern Croatia. The Austrian government and representatives of Austrian industry could strive to expand this automobile cluster across the border to northern Croatia in order to pursue possible common interests and thus to carry out important development work in integrating Croatian industrial companies into the international value chains.

Political developments will also be crucial in helping long-term economic sustainability

In order to give the people of Croatia better prospects for the future, the political system also needs to be stabilised. In the border regions with Bosnia and Serbia, the legacy of the war in the 1990s can still be clearly felt. The Austrian and other EU governments could help here by providing specialists in mine clearance, which is progressing only slowly. Together with representatives from the Austrian provinces of Carinthia and Burgenland, the Austrian government in particular could also build on its own diverse experience as a mediator in minority issues and become involved, for instance, in solving the place-name disputes with the Serbian minority in eastern Croatia.

‘This article is based on M. Holzner and H. Vidovic (2018), ‘Wirtschaftliche Perspektiven für Kroatien’, wiiw Research Reports in German language, No. 9, March.