New migration challenges for the EU in the 2020s

01 June 2021

Migration to the EU will increase in the next decade, especially from Africa and the Middle East. EU policy must react accordingly.

By Richard Grieveson, Michael Landesmann, Sandra Kovacevic and Isilda Mara

photo credit: iStock.com/fcscafeine

- A new wiiw study establishes that migration to the EU from Africa and the Middle East will continue to increase in the coming years.

- It will be driven by sustained income gaps, weak institutions, state fragility, environmental changes and the risk of natural disasters and conflicts.

- Meanwhile there will be pull factors in the EU, not least the decline of working-age populations and consequent shortages of labour and skilled workers.

- Greater restrictions on migration would slow the growth of migration relative to the baseline, but would by no means stop it. Moreover, this could prompt an increase in irregular migration.

- Lowering restrictions on migration would increase migration flows, but the materialisation of political and climate risks in the source countries would also lead to much greater immigration to the EU than under the baseline scenario.

- EU migration policy must evolve in order to meet the challenges that the coming decades will bring.

- The most important steps include managing future migration flows via a partnership approach (particularly in relation to Africa), encouraging circular migration and devoting sufficient resources to support refugees in areas affected by conflict and natural disasters.

For most of the past few decades, the defining feature of European migration was its East-West nature. The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the outbreak of various political conflicts in that region, and later the accession of many CEE countries to the EU (and freedom of movement), has led to a large population movement to wealthier and generally more politically stable parts of Western Europe.

However, the 2015-16 migration crisis made clear a trend that had already been in place for some time: that the EU was facing a new set of challenges than in the past, with most of the migrants and asylum seekers coming from much further away. The 2015-16 crisis did not in itself represent a dramatic change, but rather an intensification of a decades-long process of increased migration from Africa and the Middle East to Europe. Migration into Europe has become increasingly dominated by South-North rather than East-West patterns.

In order to better understand the way that migration patterns towards the EU have evolved, to quantify them, and to provide suggestions on future policy steps, wiiw undertook a new study. The study was divided into three parts.

Step 1: Measuring the flows and understanding the reasons

In the first part of the study (Working Paper 198), we applied a gravity modelling approach to analyse patterns and drivers of the South-North migration corridor over the period 1995-2020. Within this, we explored bilateral mobility patterns from 75 sending countries in Africa, the Middle East and the Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries to the EU, UK and EFTA. The purpose of the study was to investigate the main drivers of mobility to the EU, UK and EFTA from the identified source regions, the importance of push-and-pull factors of mobility, and the role played by migration policies to determine migration flows from these regions towards the EU, UK and EFTA. Here we relied on the new POLMIG database compiled by wiiw.

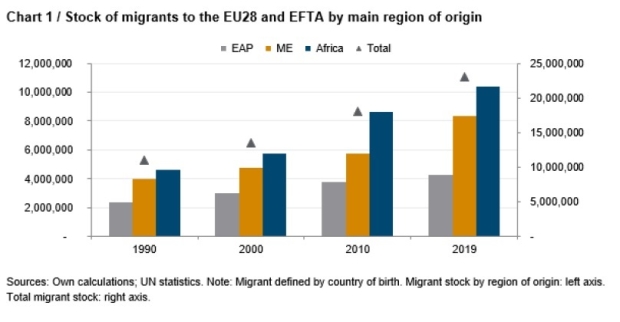

Over the past three decades immigration from Africa and the Middle East to the EU, UK and EFTA increased substantially, to above 23 million (Chart 1). Our gravity modelling results established that income gaps, diverging demographic trends, institutional and governance features, political instability, and higher climate risks in the neighbouring regions of the EU, drive migration flows along the South-North corridor.

The income level gap between the European destination countries and the income levels in Africa, the Middle East and EaP countries is an important pull factor. In general, the evidence suggests that closing this income gap would reduce migration. However, for migration from Africa to the EU, UK and EFTA, we find evidence for an inverted U-relationship between the level of income and migration. In line with other studies, this suggests that starting from low levels of income, income growth can lead first to increased outward migration, as would-be-migrants can cover the costs of migration to further-away countries of destination more easily. Only in the long run, with further increases in the levels of income, would outward mobility from Africa decline.

The EU has previously responded to migratory movements from Africa and the Middle East by signing a number of partnership agreements dealing with the issues of security, development, border management, illicit trafficking and migration. In our study we tested those migration policies that affect entry and stay in the country of destination, for example policies that either facilitate or restrict migration. Changes towards more restrictive migration policies regarding access and entry to the destination country appear to be important factors for deterring mobility. By contrast, factors that facilitate mobility seem to play only a minor role in spurring mobility.

Our results suggest that the push and pull factors driving outward migration from Africa and the Middle East to the EU are likely to persist for many years to come. This will be the case at least as long as the gaps in terms of income, quality of institutions and state fragility remain wide and the risk of natural disasters and conflicts remains high. Ageing populations in the EU will also continue to create demand for workers, thereby attracting young migrants from Africa and the Middle East. Furthermore, increases in income levels – making mobility more affordable – will encourage migration by younger people in particular from Africa and the Middle East.

Step 2: Forecasting future migration flows and scenarios

In the second part of the study (Working Paper 199), we aimed to calculate long-term potential mobility from Africa, the Middle East and the EaP countries to the EU, UK and EFTA by applying a migration gravity model and following a scenario-based approach. Anticipating migration flows in order to ensure better management and regulated mobility has become essential, although this is an exercise subject to high uncertainty.

Based on the estimates provided by the gravity model, we forecasted future migration flows using quantitative assumptions of the different mobility drivers. We conducted the exercise for the 2020-2030 time period. In our estimates, we used the following drivers of mobility:

- Economics: Income level developments and employment conditions in destination and sending countries;

- Demographics: Population sizes of sending and receiving countries, the latter standing for the absorption capacity of the receiving countries, plus the age structure of population on both sides;

- Gravity: Former colonial relationships, physical distance, language;

- Institutions: Quality of governance, extent of democracy, existence of conflict;

- Climate: Climate change, water and food security;

- Migration policies: Restrictions on entry and stay in the destination countries.

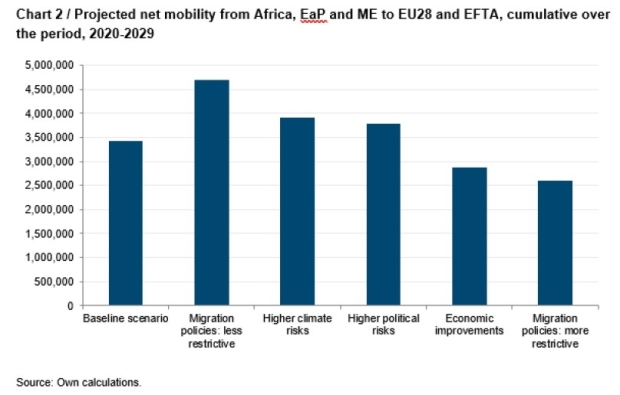

With respect to economic variables, institutional developments, political and climate risks and migration policies we adopted a scenario-based approach. For all scenarios, we find that migration flows from the identified source countries to the EU, UK and EFTA will increase in the current decade. We find that flows from Africa in particular will dominate. In the baseline scenario, in 2029 the projected stock of migrants from Africa and the Middle East to the EU, UK and EFTA countries is expected to exceed 25 million, implying a net increase in the stock of migrants by 3.4 million over this decade (Chart 2). In a more positive economic scenario, faster catch-up in GDP per capita and better economic prospects would generate 16% less net immigration to the EU, UK and EFTA compared to the baseline scenario. In contrast, a scenario involving a further deterioration of the political and social context, as well as higher exposure to environmental and climate risks, would increase net immigration to the EU, UK and EFTA by 11-15% relative to the baseline scenario.

In a scenario where it is easier for migrants to reach and stay in the EU and EFTA countries, net migration would be 38% higher than in the baseline scenario. Unsurprisingly, we find that more restrictive migration policies would reduce - but by no means stop - immigration from Africa and the Middle East to the EU. Such policies could also increase irregular mobility, as seen over the last decade in the South-North migration corridor.

Step 3: recommended policy steps

Bringing together the findings above, the third part of our project attempted to plot a way forward for policymakers (see full Policy Note here). As a first step, we set out what we see as the key framing conditions for EU migration policies in the future:

- In the coming years, even under a benign scenario, the number of people trying to get from Africa to the EU is likely to increase substantially. In the case of conflicts and environmental disasters, the numbers will be higher.

- If the EU’s response to this is ‘fortress Europe’, many people will still reach the EU. But many will also die, smugglers will make a lot of money and centrist parties in the EU will come under more pressure.

- Working-age populations in the EU will decline in the coming years and immigration can help to offset this.

- EU citizens support providing asylum for refugees, and have become more sympathetic since 2000. However, attitudes towards irregular migration have hardened.

- EU citizens are not – in the majority - against immigration, but they want migrants to integrate.

- EU citizens want migration to be managed. Surges and perceptions that migration is ‘out of control’ can quickly erode popular support and drive centrist politicians towards hard-line policies.

- EU citizens care where migrants come from. There is much less popular support for migration from outside the EU. However, the demographic trends indicate a further trend towards South-North migration, so that formulating and implementing a forward-looking policy to manage migration along this corridor will have to become a priority.

- A lowest common denominator approach will not produce satisfactory results.

- Migrants’ preferred locations are driven by financial considerations and existing networks, and are largely limited to a restricted number of Northwest EU+EFTA member states.

Having set out these framing conditions, we also build on the framework of sustainable migration established by Betts and Collier in 2018. Sustainable migration must meet the following conditions:

- Democratic support of the receiving society.

- Meets the long-term interests of the receiving state, the sending society and migrants themselves.

- Fullfils basic ethical obligations.

Taking all this into account, our proposals for EU migration policy in the future are the following:

- Manage migration with a partnership approach between the EU and Africa: EU economies would get the workers they need to fill labour and skills shortages, EU citizens would gain a sense of control, and the journey would be safer for migrants themselves. Only those with a realistic chance of being able to stay legally – because of work, study, family reunification or asylum reasons – would make the journey.

- Encourage circular migration and make it easier to send remittances: Migrants would get the opportunity to study and train in the EU for a fixed period, before they go back to their home countries to apply what they have learned. EU policy should also be geared towards reducing the transaction costs of remittances.

- Be flexible and have resources (money, technical) ready to be deployed quickly in case of refugee crises: The EU should provide more money for refugees to be housed humanely close to conflict areas, and in general take on a much larger burden to support refugees (the vast majority of refugees are currently in low- and middle-income countries). It should also set aside funds and technical expertise that can be deployed quickly to support poorer countries that experience a rapid increase in refugee arrivals owing to a new conflict, environmental disaster or change in strategy by smugglers.

- Accept relocation realities from the perspective of both receiving countries and refugees themselves: If a clearly identifiable group of EU member states is going to end up taking all successful asylum applicants, those countries could decide to pursue their own course, pooling resources and making decisions as part of a smaller group within the EU.

- Devote more resources to development co-operation, but for the right reasons: Providing resources and technical expertise to support economic development is a way for the EU to show its commitment to countries of origin, and to provide incentives for them to participate fully in the management of migration flows.

- Tackle integration: Including recognition of qualifications and strong support to boost new migrants’ language skills.

- Communicate properly and honestly with prospective migrants about the realities of the journey to the EU and the legal basis for staying.

Press Releases

Related Projects

Related Publications

- Migration from Africa, the Middle East and European Neighbouring Countries to the EU: An Augmented Gravity Modelling Approach

- Potential Mobility from Africa, Middle East and EU Neighbouring Countries to Europe

- Future Migration Flows to the EU: Adapting Policy to the New Reality in a Managed and Sustainable Way

- wiiw - POLMIG Database: An Inventory of Migration Policy Changes in Europe, 2013-2019