Five big questions for the future of the EU budget

26 April 2018

It is highly likely that transfers received by EU-CEE countries from 2021 onwards will be lower than now, which will hit growth and public investment.

By Richard Grieveson, Philipp Heimberger, Mario Holzner, Armon Rezai, Sandor Richter, Roman Römisch, and Robert Stehrer

Photo: EC audiovisual service

- The current round of EU budget negotiations look set to be even more tortuous than usual, and there is a serious risk that the EU members in Central and Eastern Europe (EU-CEE) will end up receiving lower levels of transfers from 2021 onwards.

- A desire to direct more funds towards crisis-hit countries such as Greece and irritation with EU-CEE in parts of Western Europe point in this direction. However, the need for unanimity will limit the extent to which conditionality is introduced into the budget.

- The post-Brexit budget gap is a more serious issue, and it is far from guaranteed that other wealthy member states will fully cover this after 2020. A cut in cohesion funding from 2021 looks likely.

- Some hope that the EU will be able to raise more of its own resources in the future, and that spending priorities will be changed (including less subsidies for agriculture). However, we are sceptical about the chances of significant changes in these areas.

- If EU-CEE ends up getting less money from 2021, this will hit growth and especially public investment, which will also cause a decrease in private investment. Combined with negative demographic trends and a continued infrastructure gap, this provides another major long-term challenge for the region.

- The EU budget represents a win-win for the whole of the EU, and as such any cuts would have negative consequences for all member states. Benefits for poorer parts of the bloc have been numerous, but is important that transfers keep flowing for a prolonged period of time to cement gains achieved and ensure sustainable convergence.

- A cut in funding would make policy at the national level even more important to reduce the negative impact on growth and living standards. Reducing labour market rigidities via collective bargaining, improving human capital, and efforts at the institutional level to minimise skills mismatches are all important. Moreover, a greater share of whatever EU funding is available in the future should be focused on productive investment in sectors producing tradeable goods.

The EU is gearing up for a fight about money. Next week at a European Council meeting in Brussels, the European Commission will present its proposals for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), 2021-27.

Part of the proposal has already been leaked. The Commission reportedly wants to end the strong reliance on GDP per capita as a means of determining funding levels, and to replace it with a much broader set of indicators. These would apparently include youth unemployment, education, the environment, migration and innovation. In addition, the Commission wants to make the funding conditional on compliance with EU law. This creates the possibility that funds will be redirected from EU-CEE to Southern Europe.

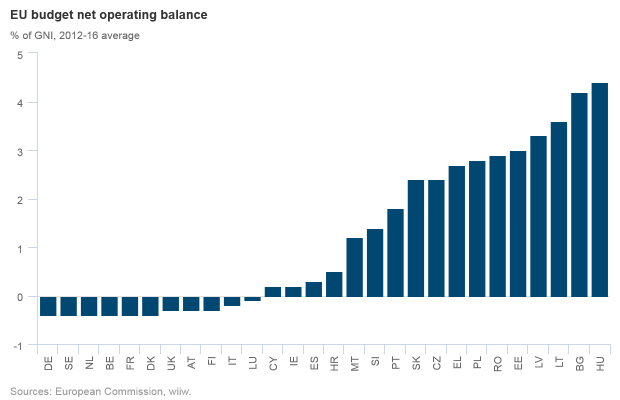

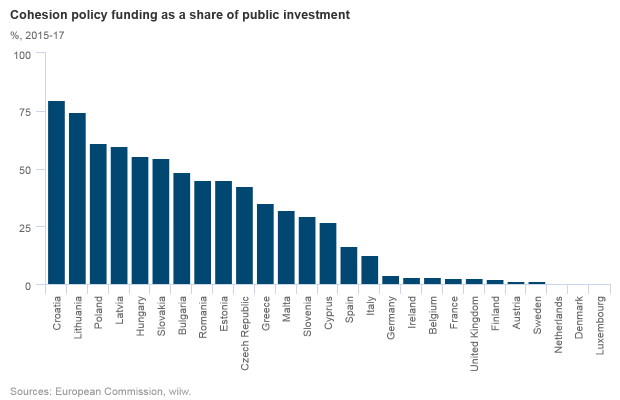

The Commission’s proposals, however, represent only one of several threats to the continued flow of large transfers from Brussels to EU-CEE countries. Among other things, there is Brexit (the UK is the second biggest net contributor to the budget) and irritation among Western European countries with parts of EU-CEE over rule of law infringements, alleged corruption and a refusal to take part in refugee reallocation schemes. This matters a lot; EU transfers are highly important for EU-CEE’s growth model and public investment (see chart below).

EU budget negotiations are always tortuous: the 2014-20 round took 18 months and several summits before an agreement was reached. However, as a result of the factors outlined above, this round of budget negotiations looks set to be the most tortuous and the most important (especially from the perspective of EU-CEE) for some time. We see five questions as particularly pressing:

1. Will the post-Brexit gap be filled, and if so who will fund it?

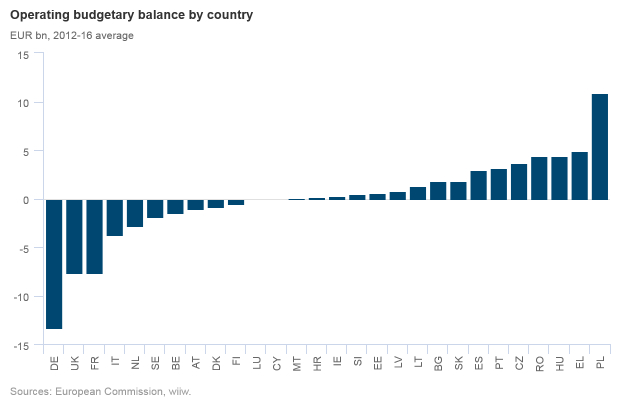

The UK’s net contribution over the five years to 2016 (latest data available) average EUR 7-8bn per year. This is not a huge amount from the EU perspective: it equates to less than 7% of total gross national contributions by EU member states to the budget in 2016. The European Commission estimates that the post-Brexit gap will be around EUR 10bn per year. A negligible increase as a share of GDP by the wealthier member states would be enough to cover the gap.

Germany and France, the two key actors in the EU, are willing to increase their contributions to help fill the gap. Moreover, Germany wants to go further, and to increase the size of the EU budget to 1.1% of the EU’s gross national income (GNI), from 1% currently. Berlin argues that this is necessary to tackle new and pressing issues facing the EU, including migration.

However, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, and Sweden—the so-called “frugal four”—are against any increase in their contributions. Representatives from these countries’ governments have been notably unequivocal in their statements on the issue. This makes it quite hard to see them backing down.

The most likely outcome is that there will be a typical EU fudge, which allows all sides to walk away claiming victory in front of their national media. This may well include an ever more complicated series of rebates. However, overall there is a good chance that the budget will be smaller after 2021.

German European Commissioner for Budget and Human Resources Günther Öttinger has already said that he expected cohesion funding to fall by 5-10% compared with current levels.

2. Will there be a change in the way that revenue is raised?

The horse-trading that accompanies EU budget negotiations, and focus on national payers and recipients, has long prompted hopes that more of the budget could be raised at the EU level. In 2016, around EUR 20bn was raised from the EU’s “own resources” (mostly customs duties), equivalent to only 14% of total revenue. Suggestions to increase the share of “own resources” have included a financial transactions tax, the raising of some value-added tax (VAT) at the EU level, and new taxes on the likes of google and facebook. France has been a leader in pushing in this direction.

Raising a greater share of EU budget revenue centrally would of course reduce the political fights around the budget every seven years. However, we are very sceptical about the chances of success. The maintenance of tax-raising powers at the national level has strong political support in many key member states. Although there are some strong arguments in favour of a common corporate tax in the EU, we see this as highly unrealistic in the current context. In fact, we think that taking taxing powers away from the national level and giving it to the EU is actually more politically difficult than getting all wealthier member states to agree to higher national contributions to the EU budget.

3. Will there be a change in spending priorities?

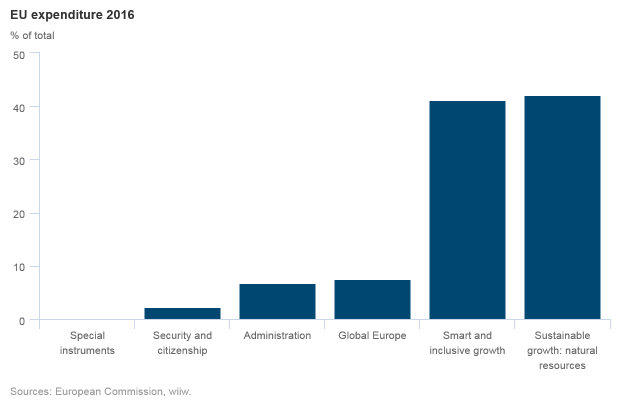

Another issue that has been floated is whether to change how the EU spends its money. Many have criticised the EU budget, notably in relation to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). In 2016, around EUR 57bn was devoted to the “sustainable growth: natural resources” component of the budget, which is dominated by the CAP. This was 42% of total spending in that year. The CAP has been criticised for, among other things, favouring bigger farms, holding back improvements in productivity, stifling competition, pushing up prices for consumers, and creating environmental problems. The Commission itself notes that 80% of CAP payments go to 20% of farmers. More generally, Brussels-based institute Bruegel has noted that the benefits from spending on the CAP and regional policy—i.e. most of the budget—are questionable.

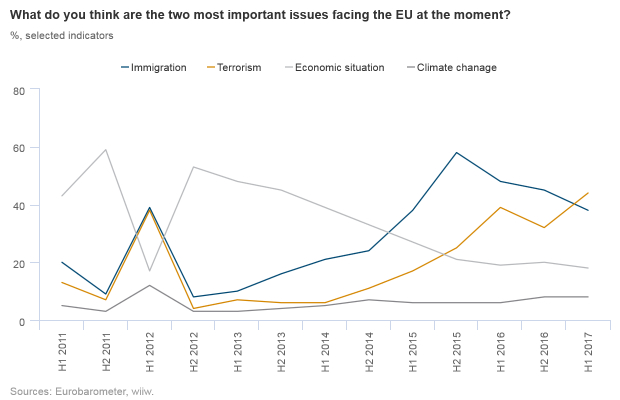

A second key consideration is the possible increased spending on particular priorities, such as defence or migration. At present, the EU spends very little in these areas, but they have shot up the political agenda in recent years (see second chart below), and in particular since the 2015 migration crisis.

A 2015 survey conducted by wiiw suggested that EU-CEE countries are not opposed to changes in EU spending priorities. Interestingly, on balance survey respondents from the region believed that an optimal budget would see a cut in spending on “natural resources” (i.e. the CAP), combined with more money for “competitiveness for growth and jobs”.

Our view is that significant changes in the targeting of EU spending will be very difficult. This is the reality of a process involving 27 countries and requiring unanimity. If the EU budget is smaller, the CAP appears vulnerable, but France in particular will push very hard to avoid serious reductions. French President Emmanuel Macron has said that he thinks the CAP should be “modernised and more flexible”, but this does not necessarily mean “smaller”.

4. Will there be conditionality of EU funds payments?

Immediately following the global financial crisis and subsequent Eurozone turmoil, it appeared that the main division within the EU was north-south. However, in the last few years, the key divide within the bloc appears to have been east-west. Some older member states in the West of Europe have demonstrated increased irritation with parts of EU-CEE.

Member states in Western Europe have essentially voiced three criticisms of EU-CEE, all of which are relevant for future EU transfers. First, complaints about a lack of compliance with the rule of law in parts of EU-CEE, and especially Poland and Hungary. Second, there have been growing allegations of corruption in the use of EU funds in parts of EU-CEE. Third, some Western European countries have been particularly irritated by the refusal of some in EU-CEE to take part in the bloc’s refugee relocation scheme.

The chances of conditionality in EU fund payments linked to the rule of law, for example, are significant, and would certainly be problematic for countries like Hungary and Poland. However, big changes in the conditionality of payments look unlikely to us, given the need for unanimity in the budget negotiations.

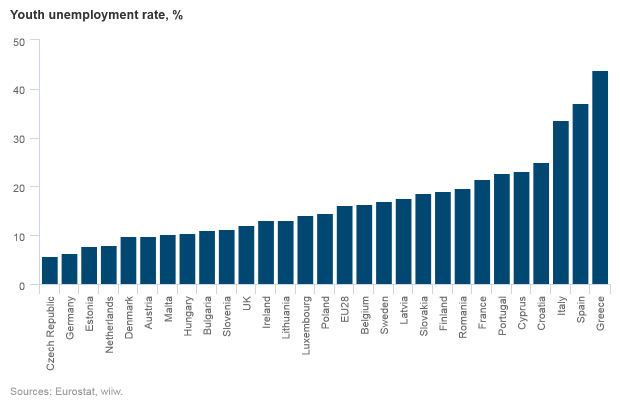

The recently leaked Commission proposals represent a new and interesting development. If future payments from the EU budget end up being linked more closely to youth unemployment, for example, parts of EU-CEE will not be in danger of losing out because of bad behaviour, but rather because of their success. As the chart below shows, most of the EU members suffering from high youth unemployment are those which joined the bloc before 2004.

5. What would a smaller budget mean for EU-CEE economies?

The fact that net inflows of EU funds can reach up to 5% of GNI (see first chart in article) makes them very important for EU-CEE countries. It is clear that any reduction in EU transfers would materially affect economic growth. This is even more the case because by the time the new budget period starts in 2021, we expect rates of economic growth in the region to be much lower than is currently the case.

Based on inflows in the five years to 2016, Hungary and Bulgaria are the most exposed to this, followed by the Baltic states, Romania and Poland. Only Slovenia is really in a position where it would be largely unaffected, even by a sharp reduction of inflows from current levels. Croatia also tends to receive less, although this is generally to do with the fact that it only joined the EU in 2013, and its poor absorption rate (something that appears to have been improving recently).

Losses for at least parts of EU-CEE from the new budget could be even higher if spending priorities change. If the CAP is cut, for example, several countries in EU-CEE would lose out disproportionately. Per capita, the Baltic states and Hungary would lose the most. In absolute terms, the clear losers would be Poland and Romania.

Public investment would be particularly badly hit in the scenario of an across-the-board reduction in funds. In 2015-17, cohesion policy funds accounted for over 40% of public investment in every EU-CEE country except Slovenia (see chart below). For Croatia the figure was 80%. wiiw research has highlighted how public investment dipped in many lagging regions after the crisis, making continued EU funds for this purpose even more important.

Policy implications

On balance, EU structural and cohesion funds in particular are an good thing. Payments into the budget from wealthier parts of the EU are extremely modest relative to these countries’ overall budgets, yet they matter a great deal for poorer parts of the bloc. In return for modest outlays relative to GDP, wealthier EU states (especially Germany and Austria) provide support to important markets for their goods. The political gains have also generally been significant: EU transfers have helped to cement democracy and the market economy in EU-CEE (albeit with some backsliding recently in certain parts of the region). Western European firms have taken huge advantage of the stability in EU-CEE to outsource production.

wiiw research has demonstrated that EU transfers can have a positive impact on firms’ productivity (although this is far from always the case). We find that most lagging regions have successfully used EU funds to improve competitiveness, technology and the labour market. Our research concludes that EU funds have improved accessibility and connectivity, quality of life, and the business environment for a large share of population in the bloc’s poorest regions. However, we also note that, given the extent of these countries’ development needs, a continuation of current policies (including EU funds inflows) need to be maintained for an extensive period in order to achieve sustained convergence with wealthier parts of Europe.

Should EU funding for EU-CEE be cut, this would make policy at the national level even more important to reduce the negative impact on growth and living standards. wiiw research indicates that, for so-called lagging regions, reducing labour market rigidities via collective bargaining, improving human capital, and efforts at the institutional level to minimise skills mismatches are all important. Moreover, we believe that whatever EU funds continue to flow into the EU’s poorest regions, these should be focused in the future more on productive investment in sectors producing tradeable goods.