Ten themes for CESEE in 2019

25 January 2019

External conditions have deteriorated, and the regional growth outlook is more subdued than was the case in 2017-18.

For the third year in a row, wiiw is producing an outlook of the key themes for our region in the coming year. Looking back to our last outlook from the beginning of 2018, it seems that most of our expectations played out.

2018 in review

At the start of last year, we expected growth across the region to remain strong (and potentially strengthen). Economic activity remained impressive in the EU member states in CESEE, with some posting even stronger rates of growth than in 2017. Meanwhile growth picked up markedly in the Western Balkans, and especially in Serbia. The CIS and Ukraine remained the laggard, particularly Russia. Turkey continued to boom in the first half of the year, but the economy slowed significantly in H2.

At the start of 2018, we also highlighted concern over potentially destabilising imbalances in Romania and Turkey, and argued that big policy changes would be required to prevent more serious overheating problems in both. Although in both countries the authorities did respond, in Turkey this came very late, and not before a major sell-off in the lira. We also highlighted that Turkey was particularly exposed among CESEE countries to US monetary tightening, which turned out to be correct. For monetary policy in the region specifically, we argued that inflation would rise gradually outside of Russia and the CIS, but not dramatically, and that therefore central banks would only proceed cautiously if at all.

On the political side, we correctly highlighted that the Italian election would cause bigger problems for the eurozone than previous polls in the Netherlands, France, Austria and Germany. We also noted the possibility of an early election in Turkey, which turned out to happen and add to volatility there. However, for the region as a whole, we were right to note that although political noise would remain high, the economic implications would be limited. Many of the countries in CESEE with the most apparent political risk (such as Poland) are also among the fastest growing. Finally on politics, we were right to expect east-west divisions in the EU over issues like the post-Brexit budget to remain, and even widen.

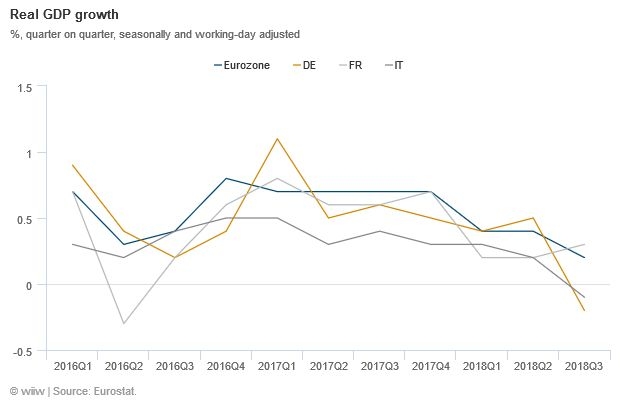

One thing that we got wrong was that we were too optimistic on the eurozone’s ability to sustain its impressive momentum from 2017. In the end CESEE grew strongly in spite of, not because of, growth trends in the single currency area. Economic performance in the Eurozone was overall mixed, but at the aggregate level momentum slowed quite visibly as the year went on. Of particular concern is the slowdown in Germany.

The World in 2019

Events in the global economy and geopolitics will be very important for our region this year. CESEE is full of small and medium-sized open economies. It is also highly reliant on the eurozone for demand, which ties it indirectly into the global economy, making events in the US and China also important. Politically, parts of the region are also within the orbit of other powers such as Russia and Turkey. China, via its 16+1 initiative, is also increasingly making its political presence felt in the region.

CESEE’s important economic, financial and political links to the major world powers means that it is also exposed to the development of the so-called “new normal”. Ten years after the financial crisis, it is clear that the world has changed, and that a return to pre-crisis normality is not on the cards. The post-Bretton woods system has been on major monetary life support for a decade, and even the so-far limited policy normalisation by the Fed has now had to be reconsidered owing to major turbulence in financial markets and weaker growth in China. The political shockwaves in the wake of the crisis, not least in Europe, are still being felt. Financial markets are volatile, and several countries in CESEE (largely Turkey and parts of the CIS and the Balkans) have loaded up on cheap dollar debts over the past ten years, which are increasingly difficult to refinance as rates rise. Whatever comes next is likely to be challenging for many of the economies in our region.

What to expect this year in the region

Looking ahead to 2019, we expect the following themes to define CESEE’s economic fortunes. These issues will be analysed in more detail in our Spring Forecast Report, due for publication at the end of March.

1. A big year for the EU and CESEE’s place within it

2019 will be an important year for the EU. Aside from Brexit (discussed separately below), there will be European parliament elections, a new European Commission, and further debates on migration, eurozone reform, and the next (post-Brexit) EU budget. Importantly, Romania will hold the EU’s rotating presidency in the first half of the year. Many are concerned that a bad performance could reflect badly on Romania in particular and the region as a whole, but we think Romania should be given a chance to show what it can do.

In the case of the European parliamentary elections, it looks likely that populist parties—especially the far right—will gain ground (see Politico’s excellent European Parliament elections site for seat projections by country). This has caused significant unease in much of the media across the continent. However, these worries are likely to be somewhat overdone. Populist parties will not be the biggest force in European politics after the elections, and even if they do particularly well, the chances of them uniting and presenting a coherent force in the European Parliament are quite low. They will certainly be noisy and generate a lot of headlines, but the implications for policy should be quite limited. Perhaps the biggest concern is simply fragmentation, which is already making governing at the national level in many EU countries more challenging, and may well become more of an issue for the European Parliament after the election. There is also the tricky issue of how to reallocate the UK seats after Brexit.

Changes in the Commission may be significant for our region, and there is a chance of conflict over how the new president in particular is chosen. The Commission would like to continue with the Spitzenkandidaten system used last time (in an attempt to make the process more “democratic” and increase popular engagement), but some key member states are unhappy with the procedure. Last time, German Chancellor Angela Merkel was not keen on the system, while French President Emmanuel Macron is also known to be opposed. Conflict between the Commission and some powerful member states is therefore possible. EU-CEE countries may have an important role to play in this dispute.

2. Political risk will remain high on the agenda

2019 will be another important election year for CESEE. Parliamentary elections will be held in Moldova in February, Estonia in March, Ukraine in October and Poland in November. Meanwhile presidential elections will take place in Slovakia and Ukraine in March, Macedonia in April, Lithuania in May, and Croatia in December. There will also be various local elections across the region, perhaps most significantly in Turkey and Hungary.

The votes in Ukraine and Poland could be the most consequential. In Poland, another victory for Law and Justice would maintain the country on its confrontational course with the EU, and further reforms which are probably not conducive to long-term growth. Meanwhile in Ukraine, the outcome of the presidential election is highly uncertain (see our most recent Ukraine country report for full details). All of the main contenders suffer from high disapproval ratings, suggesting a general lack of faith in the country’s political class (this is hardly unique to Ukraine in the region, admittedly). Whoever wins, the country’s decisive pro-Western political alignment will not change, but policy could move to the left, and bring more conflict with outside sponsors such as the IMF. Backsliding in some reform areas has already been observed. A further “heating up” of the conflict with Russia, meanwhile, certainly cannot be ruled out.

More broadly in the region, disenchantment with politics and the political class is high. Only in the last few weeks, large-scale protests have been visible in many countries, including Serbia and Hungary. There is a chance that these protests will continue, and that one or more governments may fall as a result.

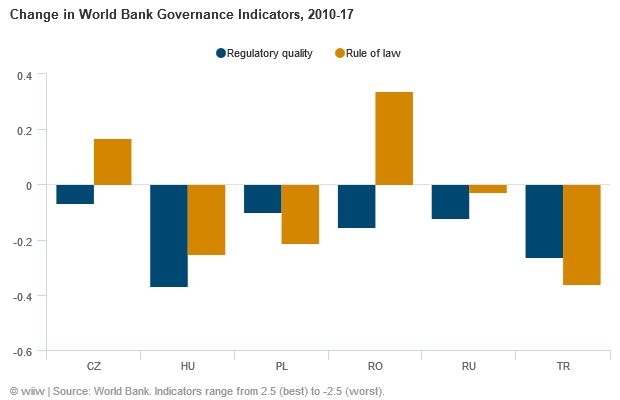

Meanwhile, institutions in the region are likely to continue to come under attack from more autocratic politicians. Backsliding on institutional convergence has been observed in much of the region since the global financial crisis and its aftermath, and looks set to continue. In some countries, this is a question of capacity, while in others it is related to institutional independence (in some, both have deteriorated). Turkey provides a clear example of how the undermining of institutional independence and quality can contribute to a crisis. So far, attacks on the independence and functioning of institutions in Poland and Hungary have not had serious economic consequences. However, we do not expect this to last.

3. Potential for further instability in the Western Balkans

Growing political challenges across the EU over the past ten years have led many countries to look inwards, and have significantly reduced the impetus towards further enlargement. This has been compounded by Brexit, with the UK having been one of the chief backers of expansion of the EU. However, 2018 saw a new Commission strategy for further expansion, have put it firmly back on the agenda.

Any further big delays to accession could increase disenchantment in the Western Balkans, contributing further to existing tensions, most notably between Serbia and Kosovo. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a particularly problematic case, and the risks of internal conflicts there heating up should not be underestimated. Russia’s role in both Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina is likely to be important, at least in the short term. Developments in Macedonia will also be key to watch. Our view is that violent conflict in one or more countries in the region remains highly unlikely, however.

The role of outside actors will certainly have an important bearing on whether relative stability is maintained in the Balkans. The US role in the rest of the world in general, including in CESEE, is changing. Partly this is because of the current president, Donald Trump. However, there are also structural factors at work. The rise of China means that US hegemony is under threat for the first time in 30 years, and is necessitating a “pivot” towards Asia. As a result, US interest in and commitment to CESEE is likely to continue to weaken, irrespective of who is president.

Combined with questions about EU commitment to enlargement, this creates space for other actors in the Western Balkans. This is mostly relevant in Serbia, Bosnia and Kosovo. China is already increasing its influence in CESEE, and this will likely continue. Its relationship with Serbia appears to have become closer. Russia’s certainly has strategic priorities in the Balkans as well, but its role is perhaps over-emphasised, as it is unwilling to commit large resources to the region. China is a different case: it may be focused more concretely on commercial interests at present, but its stake in the region is likely to grow, which may lead to a more important political role over time. Meanwhile, so far Turkey’s interests in the region appear to be compatible with those of China and Russia, and it plays an important role as a mediator in some regional disputes.

All of this puts increased pressure on the EU. The continued appeal of the bloc for non-members in CESEE should not be underestimated. However, the EU’s ability to project its influence in its neighbourhood will continue to be hampered by struggles to agree common positions between all member states.

4. Brexit: EU unity has been impressive, but this is still a blow

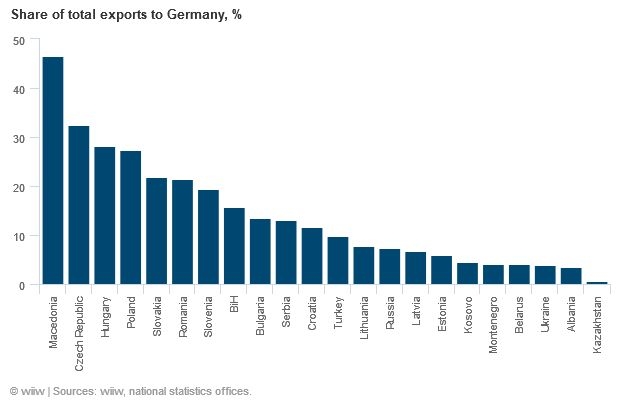

Brexit is a monumental and unnecessary act of economic self-harm by the UK. The main negative impact will be felt by the UK itself and Ireland, although there will be some spill-overs for CESEE via Germany (which is quite strongly economically linked to the UK). How Brexit materialises is highly uncertain. “No deal” would be the most economically damaging, while an orderly and “soft” exit (which still looks more likely) would have a more moderate impact.

We believe that the really significant impact, including for CESEE, is likely to be political rather than economic. The EU has shown strong unity over Brexit (as we expected it would). Opinion polls show strong (and rising) support for membership in other member states. Brexit has probably killed off the chance of any other country attempting to leave for a long time. However, even taking into account what a fool the UK has made of itself, this is a blow to the EU. For the first time (if one excludes Greenland) a country has decided to leave the EU. The process of European integration—previously basically completely one-way—has now gone partly into reverse. The UK was an awkward member state, but also a very important one, which played a crucial role in some of the EU’s biggest achievements (such as the development of the single market or the eastward enlargement). This is a big dent to the EU’s pride and will change its character, not always in a positive way.

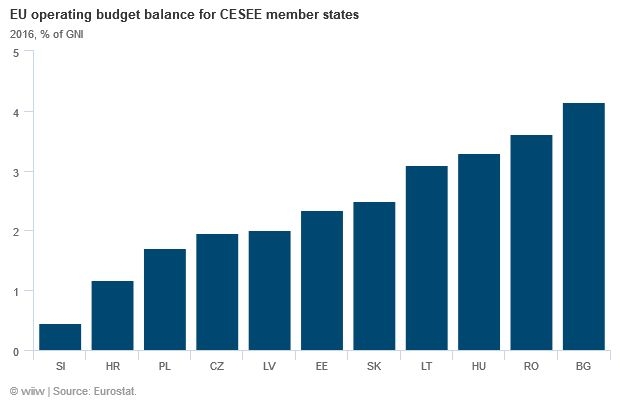

5. EU budget: EU-CEE likely to have to take a pay cut

After Brexit, the budget is likely to shrink, creating a risk of smaller inflows for EU-CEE countries from 2021. These inflows currently bring 2-5 percentage points of GDP per year for almost all member states in our region, and therefore a significant reduction would be economically painful. We see both a smaller budget, and some reallocation of funding priorities, as quite likely. The wealthier parts of EU-CEE in particular are likely to lose out (this may in the end not be a wholly negative thing, as we have argued previously). Meanwhile for the candidate countries in the Western Balkans, hopes of a significant increase in IPA funding (which we would support) are unlikely to be fulfilled.

6. More fights over migration, with CESEE countries playing a prominent role

On migration, we expect 2019 to be another frustrating year. Although the case for an EU-wide policy on migration is overwhelming (see section 1.3 in our most recent Forecast Report here), the battle lines on migration appear set, and it may take another big crisis for any serious moves towards a genuine EU solution. Recent wrangling over a small number of migrants in Malta should serve as a warning of how bad things could be if another “surge” in migration materialises, as was the case in 2015-16. Broadly, EU-CEE countries are opposed to taking large numbers (or in some cases any) of successful asylum seekers, and these governments generally have the support of their populations. Further conflict on this issue between Western and Eastern EU member states appears to be almost inevitable.

7. Euro reform will be incremental at best, leaving the single currency area exposed to the next downturn

Something similar can be said in the case of euro zone reform. On the one hand, the case for further reform is very strong. Our view is that further moves towards banking and fiscal union are necessary to insulate the bloc from the next crisis. However, on the other hand, it is clear that there are major differences between member states, and at present a compromise solution does not seem to be in sight. It is clear that Germany and some allies are not willing to take decisive further steps in the direction of banking and fiscal union. Again, a new crisis may be required before things move forward.

Many EU-CEE countries are of course already members of the euro. Several countries in the region have also aligned themselves with the so-called New Hanseatic League (formally the Baltics, but also less formally the Czech Republic and Slovakia) of fiscally conservative EU members. Meanwhile Croatia and Bulgaria in particular hope to join the single currency. The former in particular is close to being ready in our view. The government outlined its strategy for accession in 2017, but has not set a target date (reflecting an acceptance that others will also play an important role in making this decision). Euro accession would be beneficial for Croatia, but we also recognise Croatia’s history of big macroeconomic imbalances could be an issue (for a full discussion see our December Monthly Report here).

8. Slowdown in Germany (and China) means CESEE growth rates unlikely to be sustained

Economists, including us, have grappled for several months with the slowdown in Germany. Data have been quite volatile and in some ways contradictory, making it difficult to get a good grasp of underlying trends. This has been further complicated by various one-off factors, related to weather or new EU emissions regulation (and the impact on car production). However, it seems likely that German growth will be much slower this year than in 2017 and the start of 2018, reflecting weaker growth at the global level (Germany is unusually open for a big economy), and domestic capacity constraints, particularly in terms of labour. The trade war between the world’s two biggest economies may well create some positive spill-overs for Germany via trade diversion, but the overall impact is likely to be negative.

In this context, it is hard to see how CESEE can maintain currently impressive growth rates. Germany is a major trade and investment partner for almost all countries in the region. Moreover, the slowdown in Germany probably says a lot about what is currently happening in China, where growth also appears to be much weaker. Indirectly (and generally via Germany), the fortunes of the Chinese economy matter a lot for CESEE.

The region’s two biggest economies—Russia and Turkey—will again have challenging years. However, we see the underlying causes of these difficulties as very different. Russia faces a challenge of stagnation, with tight fiscal and monetary policy to safeguard macroeconomic stability taking priority over growth. Meanwhile Russia’s problem with the “four I’s” identified by then-President Medvedev in 2010—innovation, institutions, infrastructure and investment—appear no nearer to being resolved. For Turkey, by contrast, many underlying fundamentals are good, not least the positive demographic outlook. However, the country is facing a serious (and partly self-inflicted) challenge of macroeconomic stability. A recession looks highly likely, but a recovery could come in 2020 if policymakers act prudently.

9. Inflation will remain relatively subdued

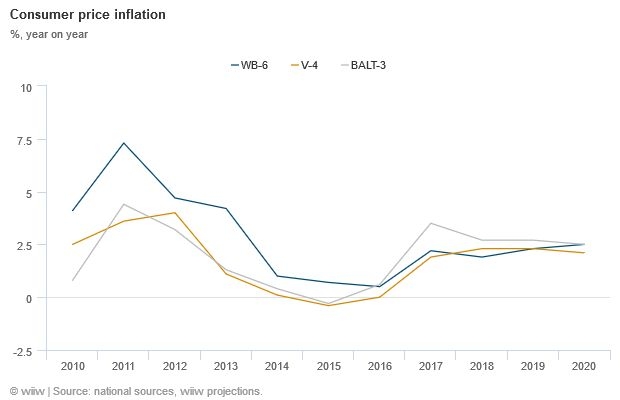

Increasingly tight labour markets across much of CESEE have pushed up wages significantly in recent quarters, with many countries registering double-digit nominal earnings growth last year. However, this has not fed through to inflation to the extent that could perhaps have been expected. We see several possible explanations for this, including rising household savings rates in most EU-CEE countries, and higher remittance outflows from the wealthier parts of CESEE. Countries such as Poland and the Czech Republic have seen inward migration rise substantially in recent years, generally from other states in the region.

We do not see these trends changing substantially in 2019, and as a result expect inflation to remain fairly well continued in most countries (Turkey is an obvious exception), even as labour markets continue to tighten. In addition, the large contribution of energy prices to headline inflation of 2018 is unlikely to be repeated this year. This means that central banks in the region are likely to only move cautiously. Much of what central banks in countries like Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Romania do will depend on the ECB, although in much of the euro zone there is still slack in the labour market, suggesting that inflationary pressures are also unlikely to materialise there.

10. Potential risks building in the financial sector

The financial sector overall in CESEE has stabilised in recent years, and the major issues faced immediately after the global financial crisis have abated. Capital levels and asset quality have improved, with non-performing loans plummeting as a share of the total over the last few years. The foreign banks which dominate the region have generally used the ECB’s quantitative easing programme to hoard liquidity, with credit expansion quite constrained. On the demand side, firms and households have often continued to deleverage, despite low interest rates.

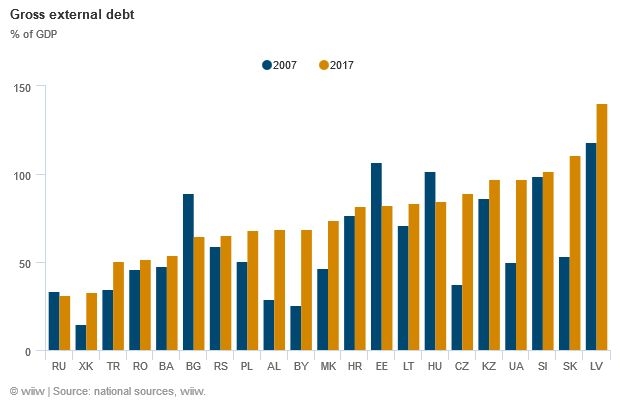

These developments have brought greater stability to the region’s financial sector, but caution is warranted (for a full discussion of financial risks in the region see our December Monthly Report). Much of this is because of developments at the global level. The US economy is in the late stage of the business cycle, and the Fed has tightened monetary policy quite substantially in recent years. This brings risks for countries in the region with large-scale dollar borrowing, particularly those who have loaded up on cheap dollars in recent years and will now have to refinance at higher rates.

Regionally, we see greater risks in Turkey, the CIS, Ukraine and parts of the Western Balkans, where the role of dollar borrowing is more significant (EU member states in CESEE tend to lean heavily towards euros, and the ECB is going nowhere fast). In terms of sector, it appears to be the case that corporates are most exposed, with governments in the region having mostly improved their external positions in recent years (although public debt overall since the crisis has risen in most places). The standout country is still Turkey, although the strong central bank response last year has mitigated these risks somewhat.